Hey bob sefcik! If you missed last week's edition – Kurt Vonnegut on kindness and community, the oldest living things in the world, meals from beloved books cooked and photographed, how a smile saved Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's life, and more – you can catch up right here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation – every little bit helps, and comes enormously appreciated.

Hey bob sefcik! If you missed last week's edition – Kurt Vonnegut on kindness and community, the oldest living things in the world, meals from beloved books cooked and photographed, how a smile saved Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's life, and more – you can catch up right here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation – every little bit helps, and comes enormously appreciated.

In May of 2013, celebrated author and MacArthur "genius" George Saunders took the podium at Syracuse University and delivered a masterpiece of that singular modern package of bequeathable wisdom, the commencement address. A year later, his speech was adapted in Congratulations, by the way: Some Thoughts on Kindness (public library), delicately designed and hand-lettered by Chelsea Cardinal. It follows in the footsteps of other commencement-addresses-turned-books, such as Neil Gaiman on the resilience of the creative spirit, Ann Patchett on storytelling and belonging, David Foster Wallace on the meaning of life, Anna Quindlen on the essentials of a happy life, and the recent compendium of Kurt Vonnegut's magnificent commencement addresses.

In May of 2013, celebrated author and MacArthur "genius" George Saunders took the podium at Syracuse University and delivered a masterpiece of that singular modern package of bequeathable wisdom, the commencement address. A year later, his speech was adapted in Congratulations, by the way: Some Thoughts on Kindness (public library), delicately designed and hand-lettered by Chelsea Cardinal. It follows in the footsteps of other commencement-addresses-turned-books, such as Neil Gaiman on the resilience of the creative spirit, Ann Patchett on storytelling and belonging, David Foster Wallace on the meaning of life, Anna Quindlen on the essentials of a happy life, and the recent compendium of Kurt Vonnegut's magnificent commencement addresses.

With his gentle wisdom and disarming warmth, Saunders manages to dissolve some of our most deeply engrained culturally conditioned cynicism into a soft and expansive awareness of the greatest gift one human being can give another – those sacred exchanges that take place in a moment of time, often mundane and fleeting, but echo across a lifetime with inextinguishable luminosity.

In this immeasurably wonderful animated teaser for the book, narrated by Saunders himself, illustrator Tim Bierbaum brings to life the author's words:

I'd say, as a goal in life, you could do worse than: Try to be kinder.

I'd say, as a goal in life, you could do worse than: Try to be kinder.

In seventh grade, this new kid joined our class. In the interest of confidentiality, her name will be "ELLEN." ELLEN was small, shy. She wore these blue cat's-eye glasses that, at the time, only old ladies wore. When nervous, which was pretty much always, she had a habit of taking a strand of hair into her mouth and chewing on it.

So she came to our school and our neighborhood, and was mostly ignored, occasionally teased ("Your hair taste good?" – that sort of thing). I could see this hurt her. I still remember the way she'd look after such an insult: eyes cast down, a little gut-kicked, as if, having just been reminded of her place in things, she was trying, as much as possible, to disappear. After awhile she'd drift away, hair-strand still in her mouth. At home, I imagined, after school, her mother would say, you know: "How was your day, sweetie?" and she'd say, "Oh, fine." And her mother would say, "Making any friends?" and she'd go, "Sure, lots." Sometimes I'd see her hanging around alone in her front yard, as if afraid to leave it.

And then – they moved. That was it. No tragedy, no big final hazing. One day she was there, next day she wasn't. End of story.

Now, why do I regret that? Why, forty-two years later, am I still thinking about it? Relative to most of the other kids, I was actually pretty nice to her. I never said an unkind word to her. In fact, I sometimes even (mildly) defended her. But still. It bothers me.

So here's something I know to be true, although it's a little corny, and I don't quite know what to do with it:

What I regret most in my life are failures of kindness.

Those moments when another human being was there, in front of me, suffering, and I responded … sensibly. Reservedly. Mildly.

Or, to look at it from the other end of the telescope: Who, in your life, do you remember most fondly, with the most undeniable feelings of warmth? Those who were kindest to you, I bet.

But kindness, it turns out, is hard – it starts out all rainbows and puppy dogs, and expands to include . . . well, everything.

Congratulations, by the way: Some Thoughts on Kindness is a beautiful read in its entirety. Complement it with Jack Kerouac on kindness, then revisit more of the greatest commencement addresses ever given: Joseph Brodsky on winning the game of life, Bill Watterson on not selling out, Debbie Millman on courage and the creative life, and more gems from , and Kurt Vonnegut.

:: WATCH / SHARE ::

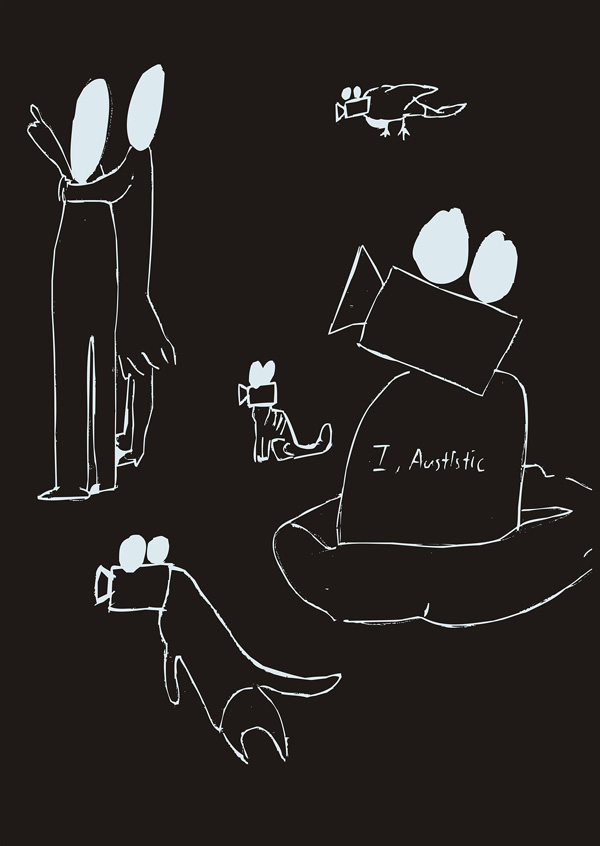

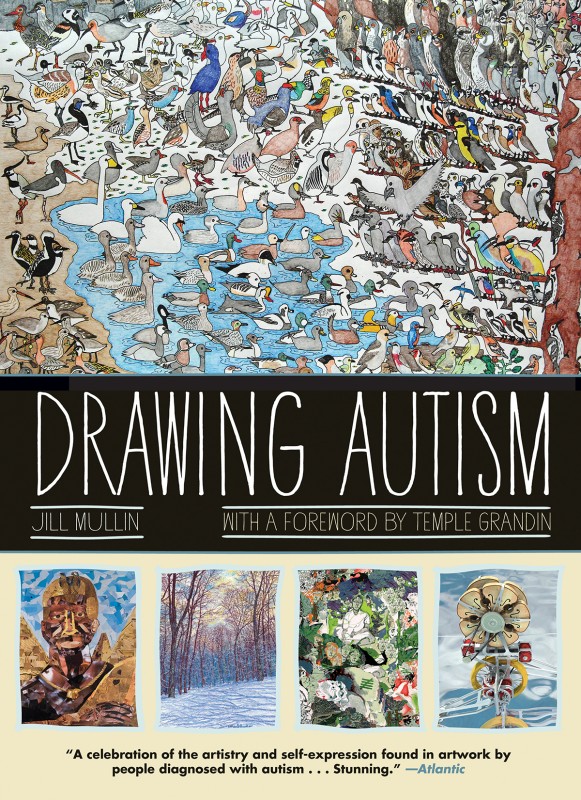

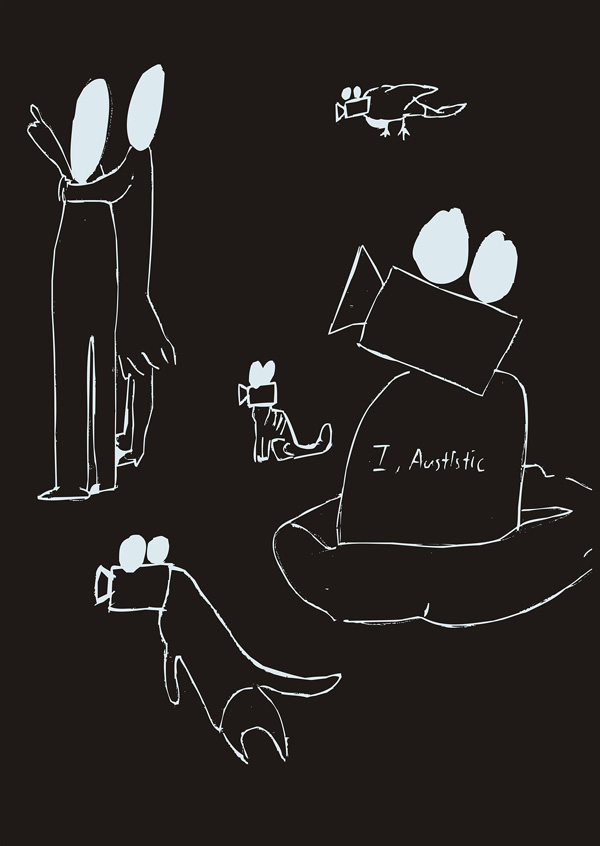

Autism and its related conditions remain among the least understood mental health issues of our time. But one significant change that has taken place over the past few years has been a shift from perceiving the autistic mind not as disabled but as differently abled – and often impressive in its difference, as in extraordinary individuals like mathematical mastermind Daniel Tammet or architectural savant Gilles Trehin. And yet despite the stereotype of the autistic mind as a methodical computational machine, much of its magic – the kind most misunderstood – lies in its capacity for creative expression.

Autism and its related conditions remain among the least understood mental health issues of our time. But one significant change that has taken place over the past few years has been a shift from perceiving the autistic mind not as disabled but as differently abled – and often impressive in its difference, as in extraordinary individuals like mathematical mastermind Daniel Tammet or architectural savant Gilles Trehin. And yet despite the stereotype of the autistic mind as a methodical computational machine, much of its magic – the kind most misunderstood – lies in its capacity for creative expression.

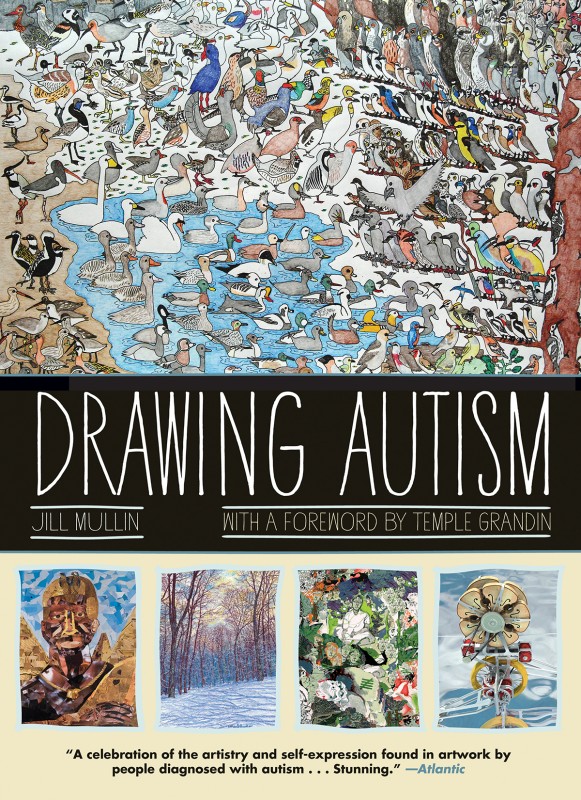

Three years after the original publication, New-York-based behavior analyst Jill Mullin returns with an expanded edition of Drawing Autism (public library) – a beautiful and thoughtful celebration of the vibrantly creative underbelly of autism, featuring contributions from more than 50 international graphic artists and children who fall somewhere on the autism spectrum, with a foreword by none other than Temple Grandin.

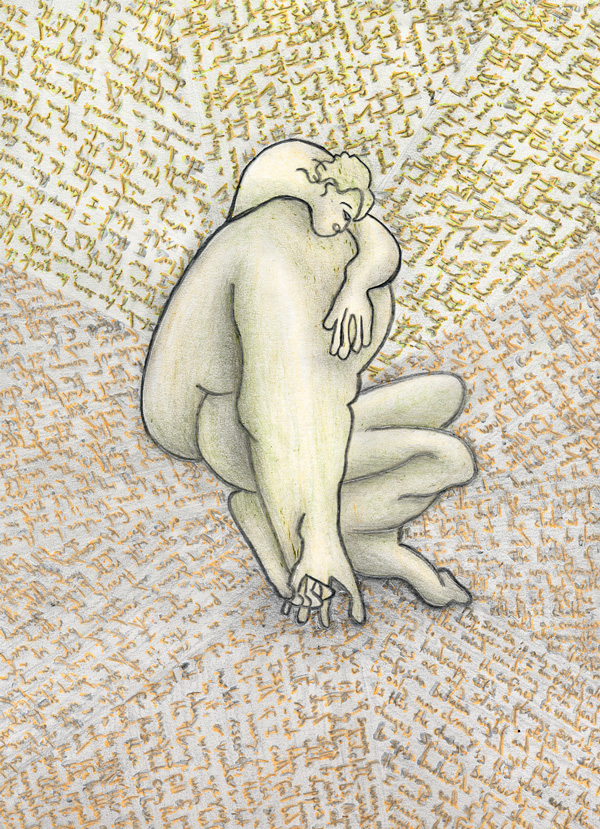

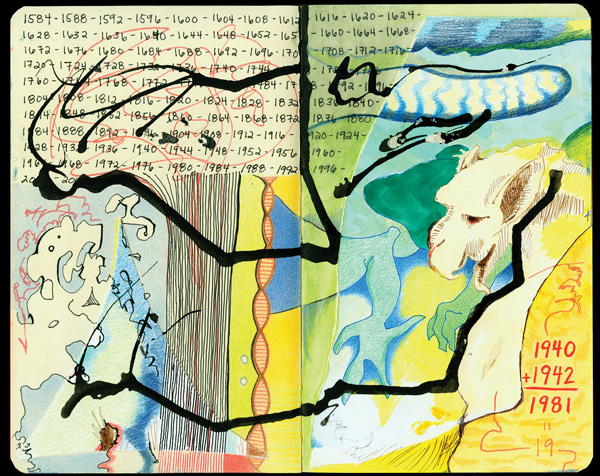

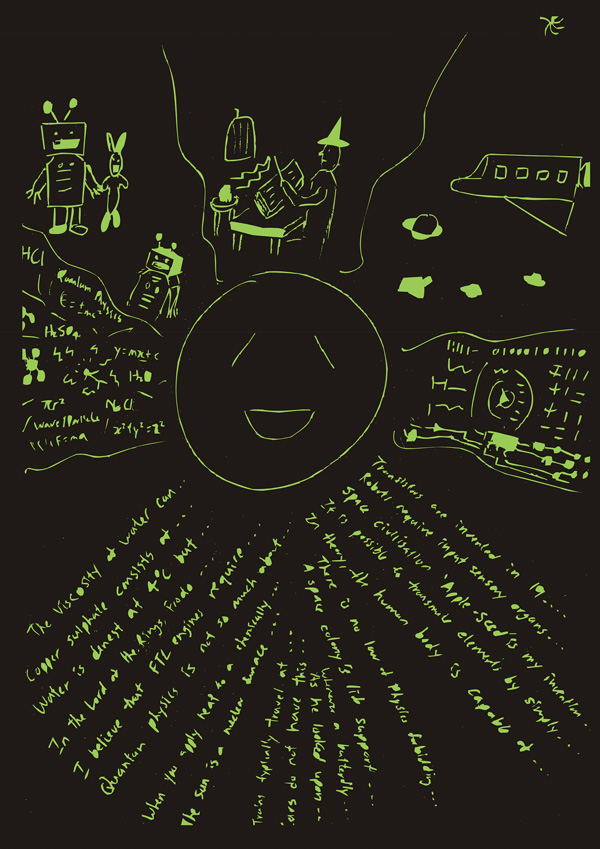

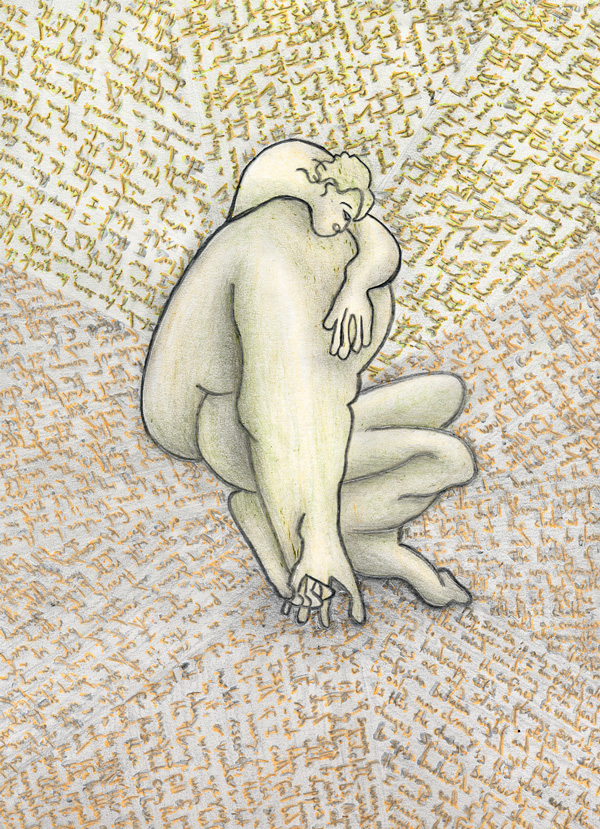

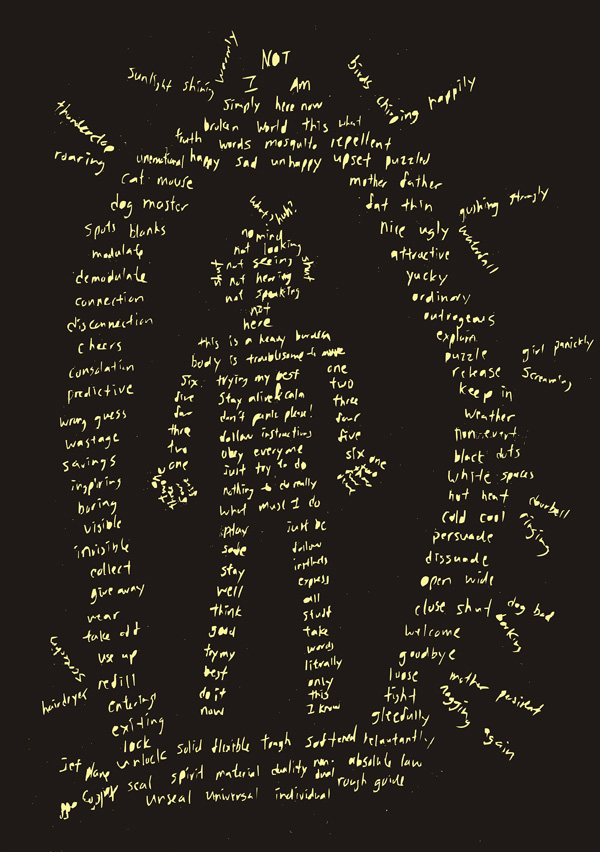

Kay Aitch: Lost in Thought

For artist Kay Aitch, who was diagnosed with Autism at the age of fifty-one, the creative process is a form of pattern-recognition – one of the typically recognized fortes of the autistic mind. She tells Mullin:

Everything around me inspires me to create art. What inspires me about creating art is the process of making marks, the feel of things, the seeing shapes and patterns in things.

Everything around me inspires me to create art. What inspires me about creating art is the process of making marks, the feel of things, the seeing shapes and patterns in things.

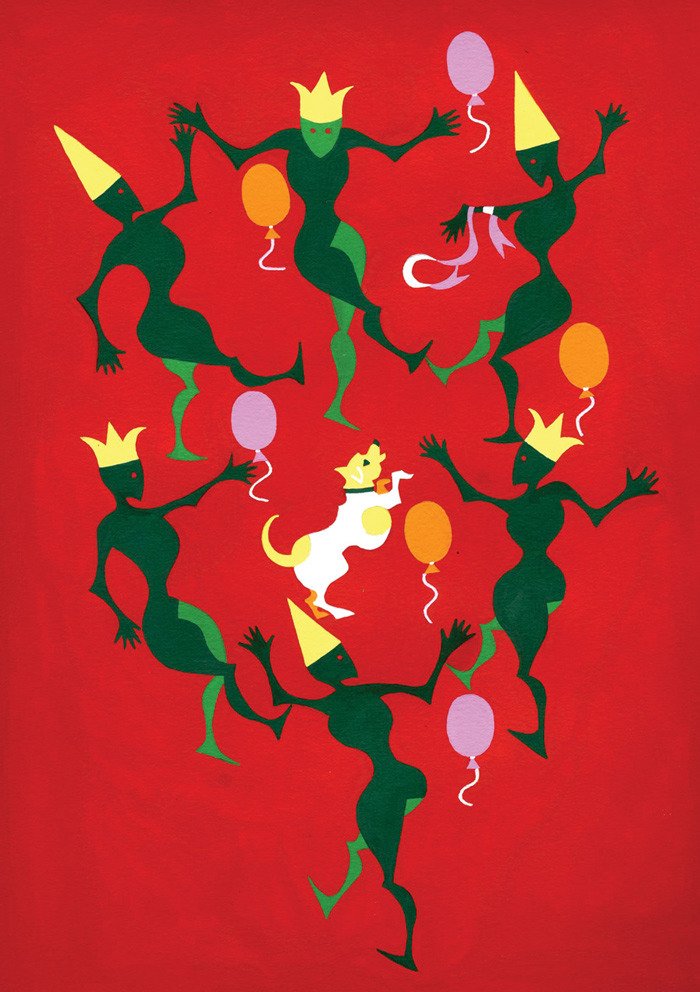

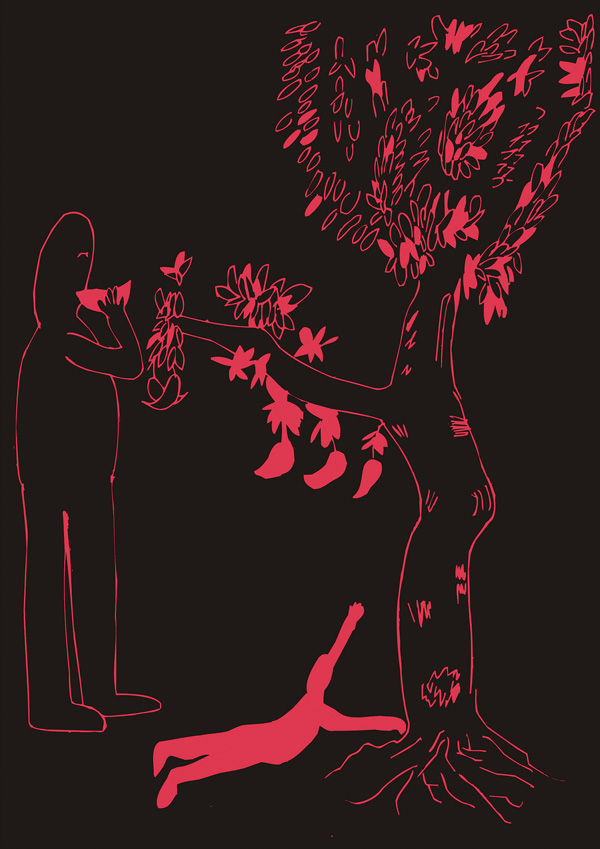

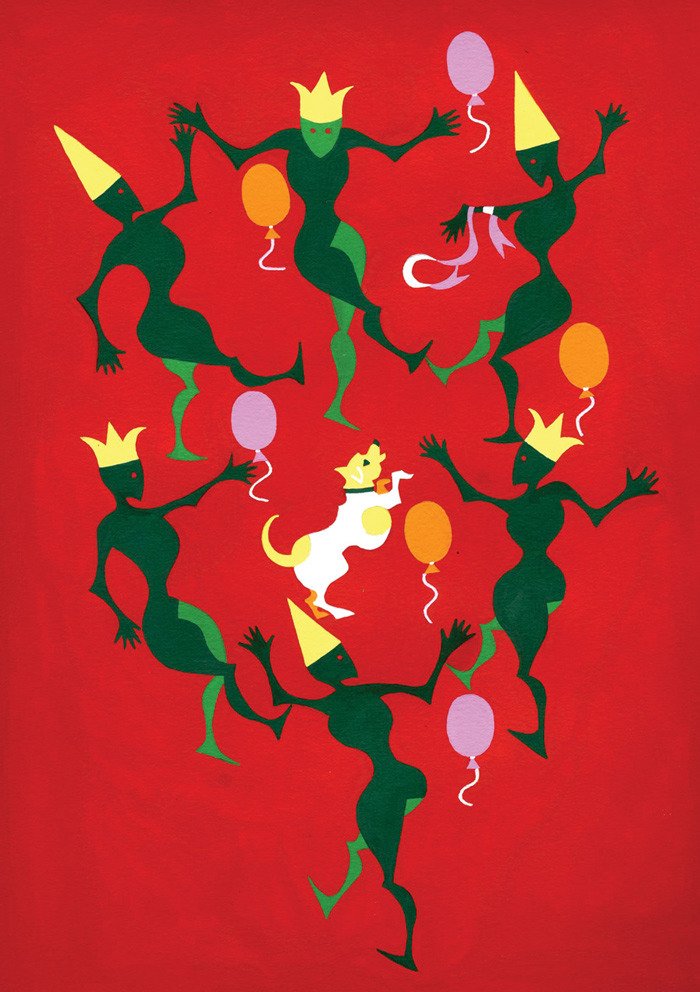

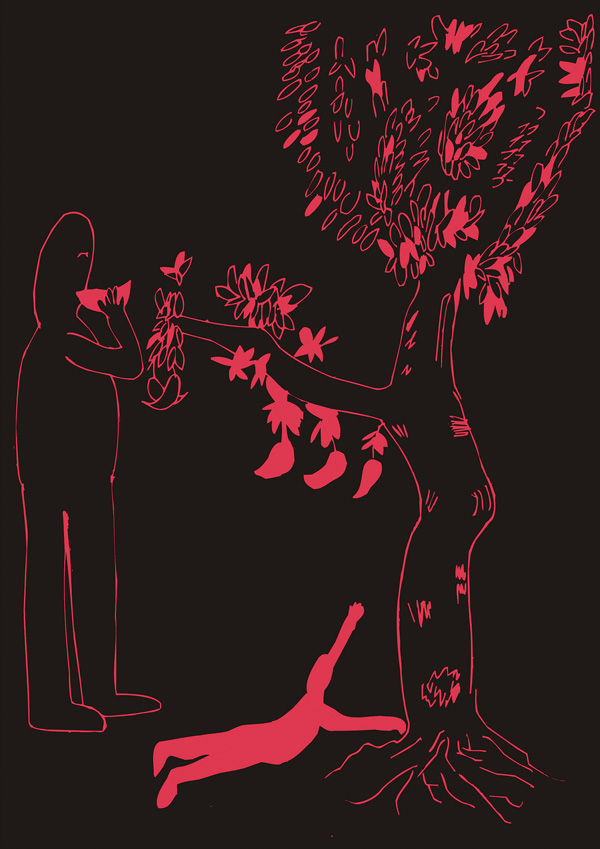

Eleni Michael: Dancing with the Dog

Artist Eleni Michael celebrates the soul-expanding power of dogs amid trauma:

This was painted in 1995, not long after I had moved into a housing project for people with special needs. I was euphoric about my new home—a self-contained flat surrounded by a huge garden in a rural setting. (This idyll did not last long.) I brought my dog Jasper with me. He was the only lively animal there and brought great pleasure to me and all of the residents in the project. They loved him too and enjoyed playing with him and petting him. Jasper was a healthy presence and completely indiscriminate with his friendships.

This was painted in 1995, not long after I had moved into a housing project for people with special needs. I was euphoric about my new home—a self-contained flat surrounded by a huge garden in a rural setting. (This idyll did not last long.) I brought my dog Jasper with me. He was the only lively animal there and brought great pleasure to me and all of the residents in the project. They loved him too and enjoyed playing with him and petting him. Jasper was a healthy presence and completely indiscriminate with his friendships.

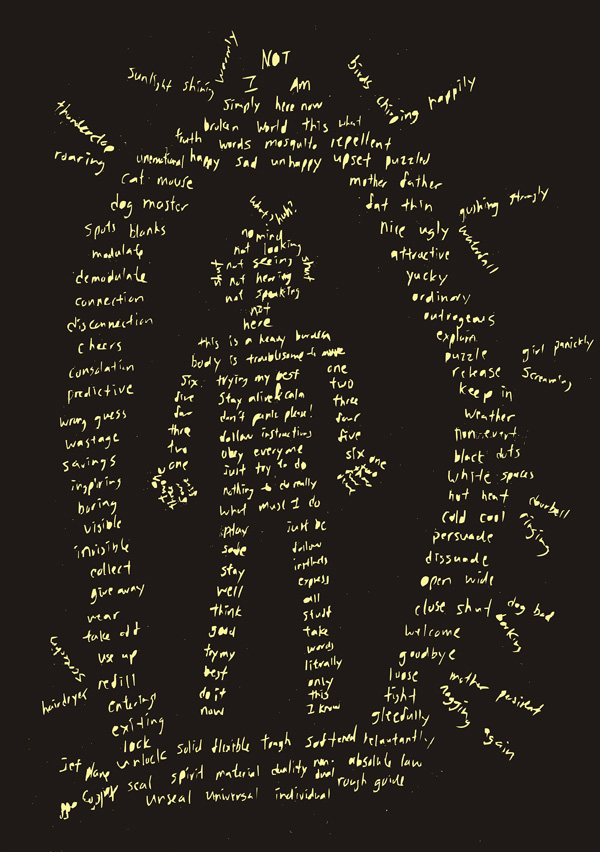

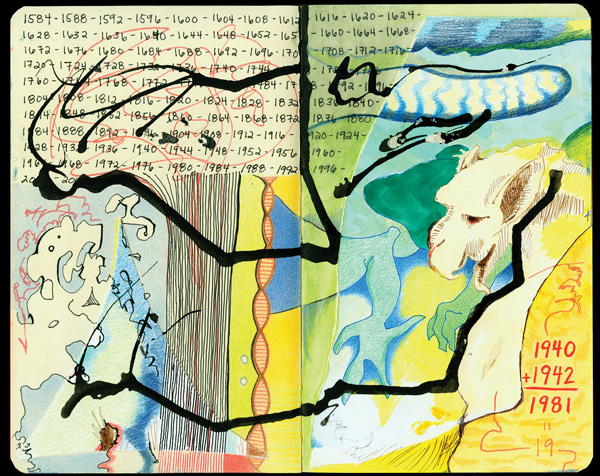

Emily L. Williams: Leap Years

Urging that "talents need to be carefully nurtured and directed," Temple Grandin writes in the foreword:

When I was a child, my mother nurtured my artistic ability. I was always encouraged to draw many different subjects. As an adult, I used my artistic talent for my business of designing livestock handling facilities. One of the lessons my mother taught me that really helped to develop my skills was to create pictures that other people would want.

When I was a child, my mother nurtured my artistic ability. I was always encouraged to draw many different subjects. As an adult, I used my artistic talent for my business of designing livestock handling facilities. One of the lessons my mother taught me that really helped to develop my skills was to create pictures that other people would want.

In elementary school, I drew many pictures of horses. Individuals on the autism spectrum often become fixated on their favorite things. As a child I would keep drawing the same things over and over. The great motivation of these fixations has been channeled into the creation of all the beautiful art featured in this book.

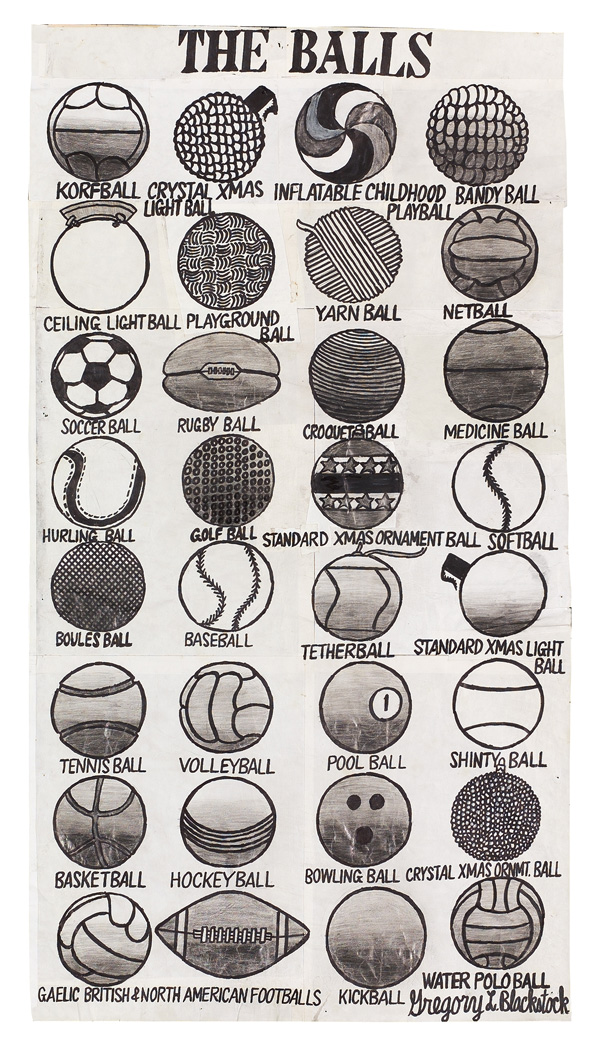

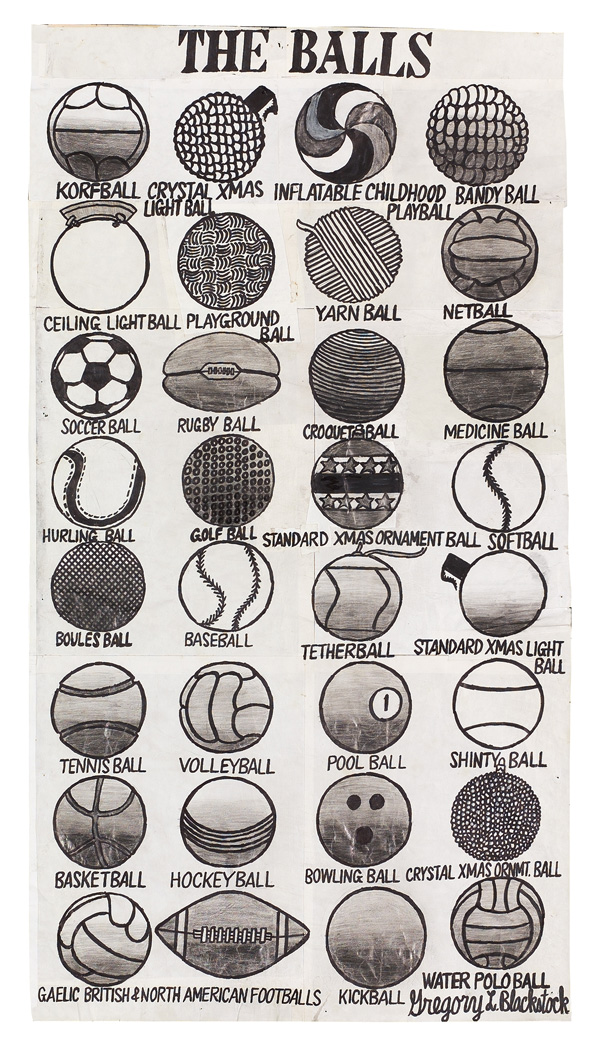

As a longtime admirer of Gregory Blackstock's obsessive visual lists, I was especially delighted to see his artwork included in the book:

Gregory Blackstock: The Balls

Repetitive patterns and visual taxonomies, in fact, are a recurring feature across a number of the pieces, such as this magnificent visual list of birds by 10-year-old David Barth:

David Barth: Birds

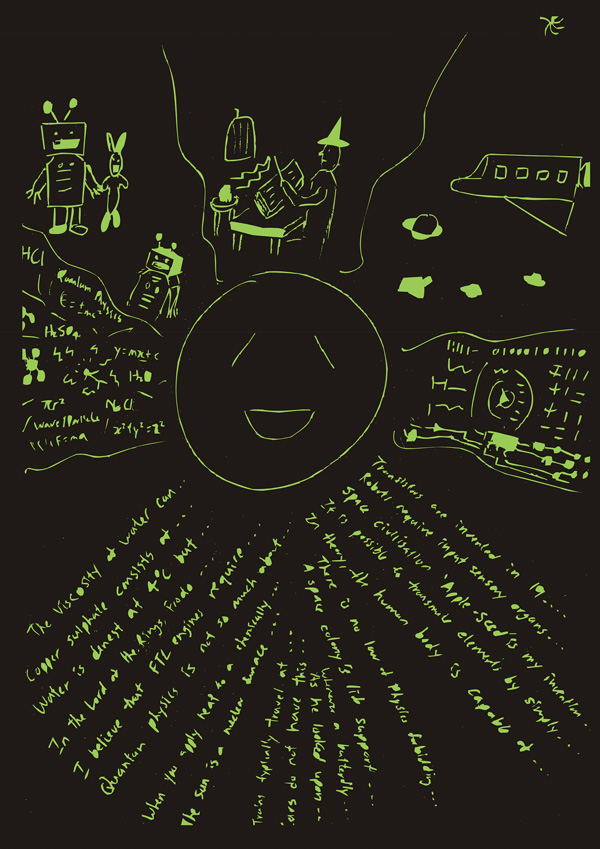

Eric Chen: Mirror Mind (1)

Eric Chen: Mirror Mind (2)

Eric Chen: Mirror Mind (3)

Eric Chen: Mirror Mind (4)

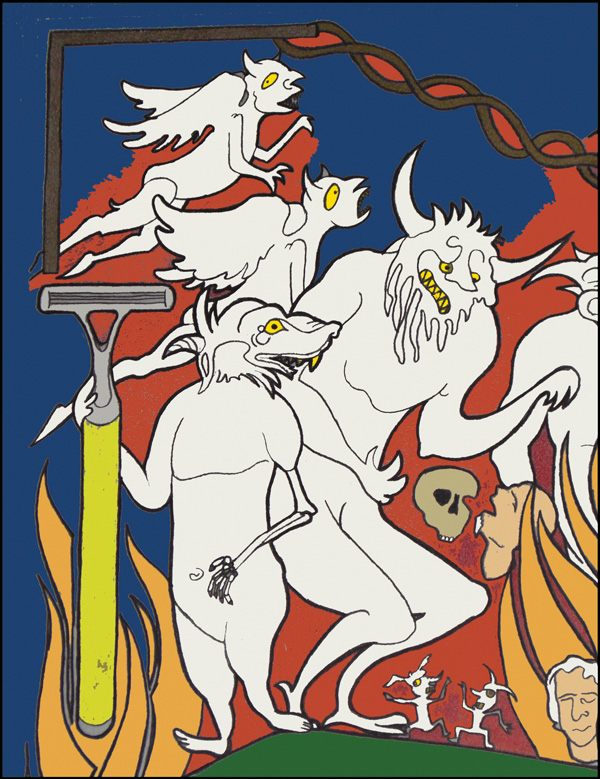

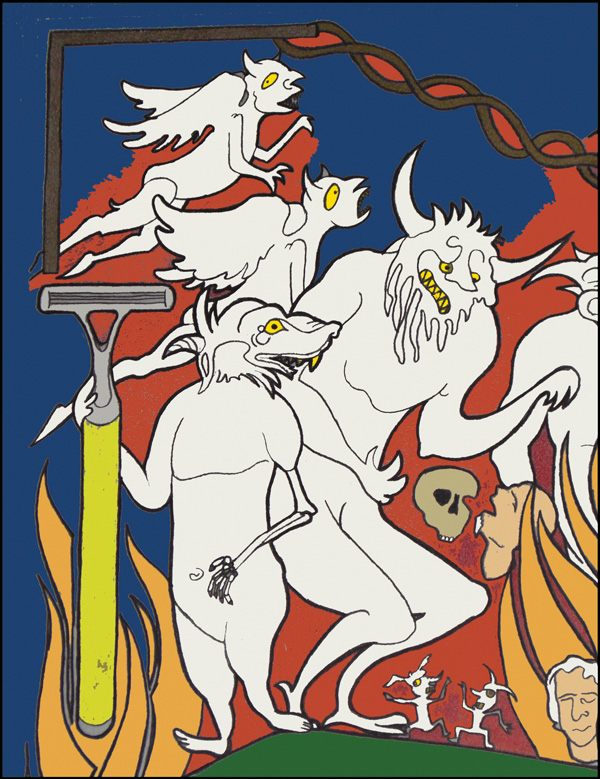

Emily L. Williams: They Take Away Your Razors, Your Shoelaces, and Your Belt

Some of the pieces blend broader symbolism with the harrowing specificity of the artists' lives. Emily L. Williams reflects on the artwork above:

This is a small portion of a larger piece that's yet to be completed. The larger piece is one of three in a series, focusing symbolically on psychiatric units, utilizing hell as an analogy. The demons in the piece were inspired by twelfth-century works depicting hell and the Final Judgment. The piece was also inspired by some of my own hospital stays in the past. While I was never a suicide risk, I always found it odd that none of the patients could have any of the items listed in the title of this piece. I understood the logic and the risk to suicidal patients, but nevertheless still found it strange to be walking around in shoes with their tongues hanging out or to have unshaven legs.

This is a small portion of a larger piece that's yet to be completed. The larger piece is one of three in a series, focusing symbolically on psychiatric units, utilizing hell as an analogy. The demons in the piece were inspired by twelfth-century works depicting hell and the Final Judgment. The piece was also inspired by some of my own hospital stays in the past. While I was never a suicide risk, I always found it odd that none of the patients could have any of the items listed in the title of this piece. I understood the logic and the risk to suicidal patients, but nevertheless still found it strange to be walking around in shoes with their tongues hanging out or to have unshaven legs.

Wil C. Kerner: Pals

For 12-year-old Wil C. Kerner, it is his grandmother who explains the inspiration behind his piece:

The key in understanding Pals is the brown-rimmed, off-white donkey ear. Four facial expressions depict the bad boys turning into donkeys in the movie Pinocchio: purple-faced Pinocchio is stunned by his new ear and considering what to do; it's too late for the horrified yellow face; the green trapezoid is oblivious to his pending fate; the blue head is looking away, hoping he's not included.

The key in understanding Pals is the brown-rimmed, off-white donkey ear. Four facial expressions depict the bad boys turning into donkeys in the movie Pinocchio: purple-faced Pinocchio is stunned by his new ear and considering what to do; it's too late for the horrified yellow face; the green trapezoid is oblivious to his pending fate; the blue head is looking away, hoping he's not included.

Drawing Autism is absolutely wonderful in its entirety. Complement it with artist Bobby Baker's visual diary of mental illness.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

"Make New Mistakes. Make glorious, amazing mistakes. Make mistakes nobody's ever made before," Neil Gaiman urged in his commencement-address-turned-manifesto-for-the-creative life. "The chief trick to making good mistakes is not to hide them – especially not from yourself," philosopher Daniel Dennett asserted in his magnificent meditation on the dignity and art-science of making mistakes. And yet most of us, being human and thus fallible yet proud, go to excruciating lengths to avoid making mistakes, then once we inevitably do, we take great pains to hide them from ourselves and the world. But this, argues Pixar cofounder Ed Catmull with the help of journalist Amy Wallace in an especially enthralling chapter of the altogether excellent Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration (public library), is a grave mistake itself – not only from an abstract moral standpoint, but also as a practical strategy for cultivating a strong creative culture in a company and an entrepreneurial spirit within ourselves as individuals.

"Make New Mistakes. Make glorious, amazing mistakes. Make mistakes nobody's ever made before," Neil Gaiman urged in his commencement-address-turned-manifesto-for-the-creative life. "The chief trick to making good mistakes is not to hide them – especially not from yourself," philosopher Daniel Dennett asserted in his magnificent meditation on the dignity and art-science of making mistakes. And yet most of us, being human and thus fallible yet proud, go to excruciating lengths to avoid making mistakes, then once we inevitably do, we take great pains to hide them from ourselves and the world. But this, argues Pixar cofounder Ed Catmull with the help of journalist Amy Wallace in an especially enthralling chapter of the altogether excellent Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration (public library), is a grave mistake itself – not only from an abstract moral standpoint, but also as a practical strategy for cultivating a strong creative culture in a company and an entrepreneurial spirit within ourselves as individuals.

What makes Catmull, who created Pixar along with Steve Jobs and John Lasseter and is now president of Pixar Animation and Disney Animation, particularly compelling is his yin-yang balance of seeming opposites – he is incredibly intelligent in a rationally-driven way yet sensitive to the poetic, introspective yet articulate, has a Ph.D. in computer science but is also the recipient of five Academy Awards for his animation work. This crusade to uncouple fear and failure is thus delivered not with the detached and vacant preachiness of self-help books and lifestyle manuals but with the sensitive sagacity of someone who has been, and continues to be, on the front lines of truly pioneering creative work.

Catmull begins by pointing out that failure, for most of us, is loaded with heavy baggage – a stigma that failure is bad and a sign of weakness, engrained in us early and hard. For all of our aphorisms about the upside of failure and even our most elegant contemplations of failure's gift, we still carry deep-seated fear and paralyzing aversion to it, to our own detriment. We are so terrified to be wrong and so uncomfortable with the unknown that we often opt for safety and security over breaking new ground. Catmull writes:

We need to think about failure differently. I'm not the first to say that failure, when approached properly, can be an opportunity for growth. But the way most people interpret this assertion is that mistakes are a necessary evil. Mistakes aren't a necessary evil. They aren't evil at all. They are an inevitable consequence of doing something new (and, as such, should be seen as valuable; without them, we'd have no originality). And yet, even as I say that embracing failure is an important part of learning, I also acknowledge that acknowledging this truth is not enough. That's because failure is painful, and our feelings about this pain tend to screw up our understanding of its worth. To disentangle the good and the bad parts of failure, we have to recognize both the reality of the pain and the benefit of the resulting growth.

We need to think about failure differently. I'm not the first to say that failure, when approached properly, can be an opportunity for growth. But the way most people interpret this assertion is that mistakes are a necessary evil. Mistakes aren't a necessary evil. They aren't evil at all. They are an inevitable consequence of doing something new (and, as such, should be seen as valuable; without them, we'd have no originality). And yet, even as I say that embracing failure is an important part of learning, I also acknowledge that acknowledging this truth is not enough. That's because failure is painful, and our feelings about this pain tend to screw up our understanding of its worth. To disentangle the good and the bad parts of failure, we have to recognize both the reality of the pain and the benefit of the resulting growth.

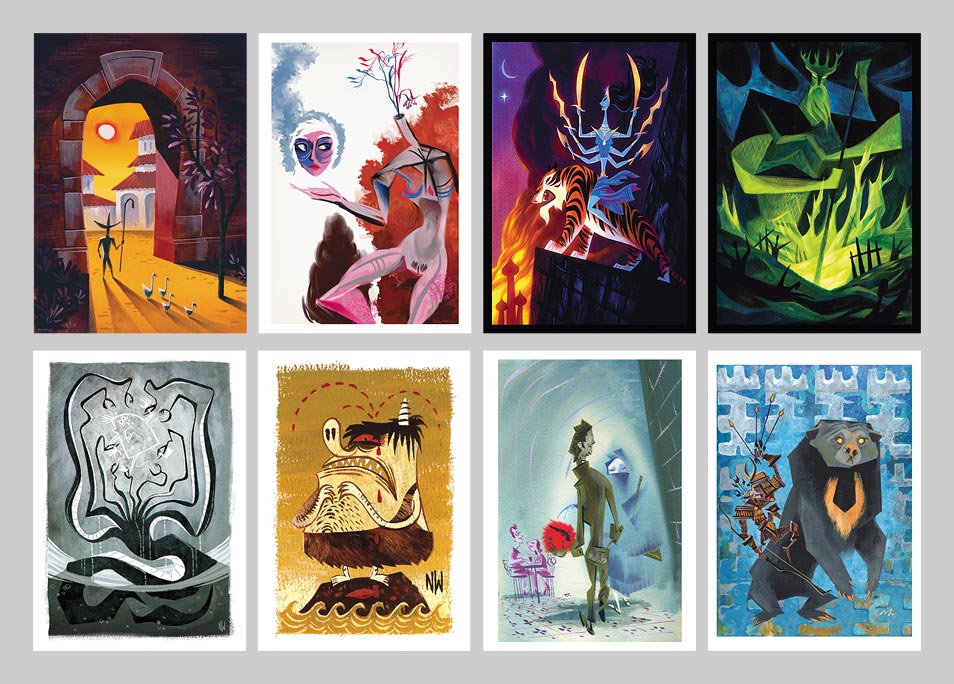

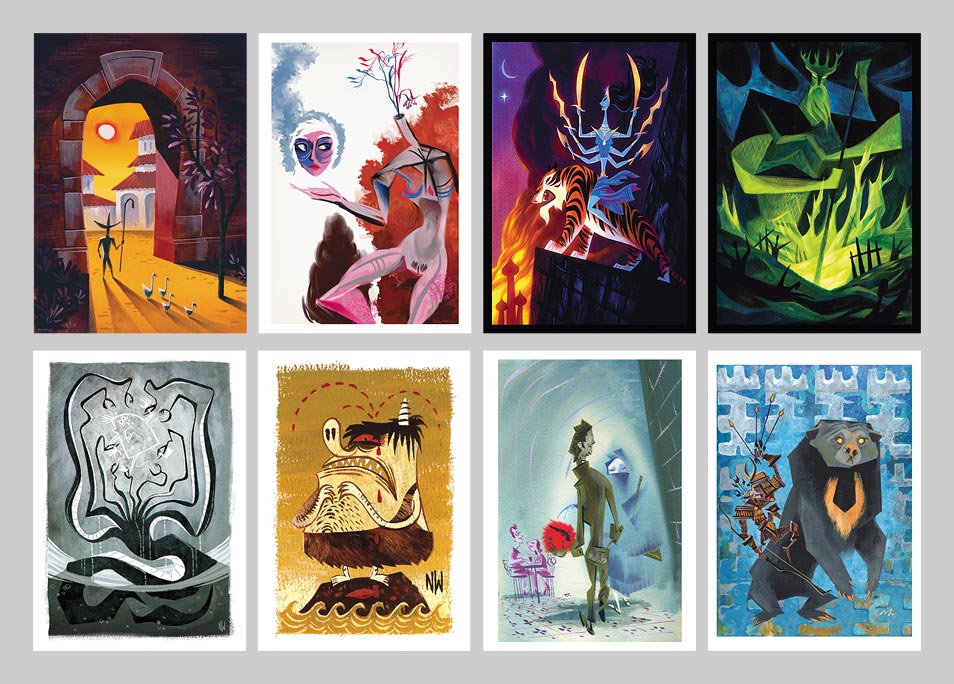

Artwork from The Ancient Book of Myth and War, a side project by four Pixar animators

Most people, Catmull argues, would go to any length to avoid failure – but not Pixar's Andrew Stanton, known around the studio for his frequent counsel to "fail early and fail fast" and "be wrong as fast as you can." Catmull quotes Stanton, who sees failure the way one ought to see learning to ride a bike – an endeavor practically impossible to master without falling and stumbling first:

"Get a bike that's as low to the ground as you can find, put on elbow and knee pads so you're not afraid of falling, and go," he says. If you apply this mindset to everything new you attempt, you can begin to subvert the negative connotation associated with making mistakes. Says Andrew: "You wouldn't say to somebody who is first learning to play the guitar, 'You better think really hard about where you put your fingers on the guitar neck before you strum, because you only get to strum once, and that's it. And if you get that wrong, we're going to move on.' That's no way to learn, is it?"

"Get a bike that's as low to the ground as you can find, put on elbow and knee pads so you're not afraid of falling, and go," he says. If you apply this mindset to everything new you attempt, you can begin to subvert the negative connotation associated with making mistakes. Says Andrew: "You wouldn't say to somebody who is first learning to play the guitar, 'You better think really hard about where you put your fingers on the guitar neck before you strum, because you only get to strum once, and that's it. And if you get that wrong, we're going to move on.' That's no way to learn, is it?"

And yet many people, including within Pixar, often misinterpret the point. Echoing Debbie Millman's assertion that "if you aren't making mistakes, you aren't taking enough risks," Catmull writes:

[Many people] think it means accept failure with dignity and move on. The better, more subtle interpretation is that failure is a manifestation of learning and exploration. If you aren't experiencing failure, then you are making a far worse mistake: You are being driven by the desire to avoid it. And, for leaders especially, this strategy – trying to avoid failure by out-thinking it – dooms you to fail.

[Many people] think it means accept failure with dignity and move on. The better, more subtle interpretation is that failure is a manifestation of learning and exploration. If you aren't experiencing failure, then you are making a far worse mistake: You are being driven by the desire to avoid it. And, for leaders especially, this strategy – trying to avoid failure by out-thinking it – dooms you to fail.

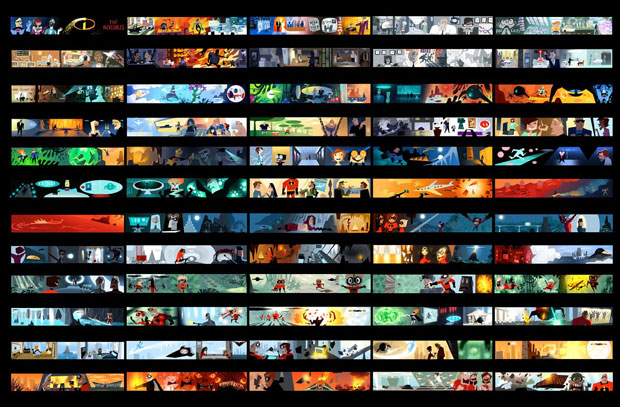

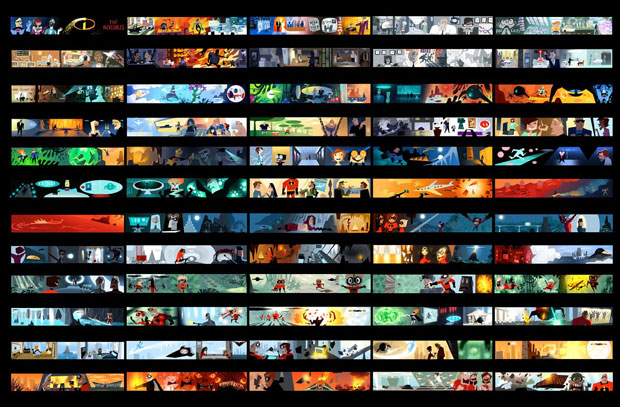

Color script for The Incredibles from The Art of Pixar

While fortifying against failure and avoiding mistakes may seem like admirable goals, Catmull argues that they are ultimately misguided. He cites the example of the Golden Fleece Awards, which in 1975 began spotlighting government-funded projects that were epic wastes of money. While such scrutiny might have its place and no doubt comes from a place of seeking betterment, Catmull argues that "failure was being used as a weapon, rather than as an agent of learning" – the awards had a chilling effect, rendering researchers and government agencies so terrified of being "awarded" that they began taking fewer risks and innovating less. (If you've read Stuart Firestein's excellent book Ignorance: How It Drives Science, you'd nod wistfully upon recognizing that this flawed ethos is the fundamental premise of science funding today, where researchers are routinely being discouraged from pursuing "curiosity-driven" experimentation and are being awarded grants for safe, "hypothesis-driven" research.)

Catmull elegantly distills the result:

In a fear-based, failure-averse culture, people will consciously or unconsciously avoid risk. They will seek instead to repeat something safe that's been good enough in the past. Their work will be derivative, not innovative. But if you can foster a positive understanding of failure, the opposite will happen.

In a fear-based, failure-averse culture, people will consciously or unconsciously avoid risk. They will seek instead to repeat something safe that's been good enough in the past. Their work will be derivative, not innovative. But if you can foster a positive understanding of failure, the opposite will happen.

For people and companies seeking to do original, innovative work, this is clearly a losing proposition. Catmull offers an antidote:

If we as leaders can talk about our mistakes and our part in them, then we make it safe for others. You don't run from it or pretend it doesn't exist. That is why I make a point of being open about our meltdowns inside Pixar, because I believe they teach us something important: Being open about problems is the first step toward learning from them… We must think of the cost of failure as an investment in the future.

If we as leaders can talk about our mistakes and our part in them, then we make it safe for others. You don't run from it or pretend it doesn't exist. That is why I make a point of being open about our meltdowns inside Pixar, because I believe they teach us something important: Being open about problems is the first step toward learning from them… We must think of the cost of failure as an investment in the future.

Creating a fearless culture enables people to explore new areas and pursue ideas with much less hesitation and trepidation, "identifying uncharted pathways and then charging down them." It also fosters a greater appreciation of decisiveness, liberating us from the constant preemptive questioning of whether the path we're about to head down is the right one. That way, Catmull argues with an inadvertent wink to Steve Jobs's famous assertion that "you can't connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards," also allows people to see what they couldn't possibly see when starting out. Catmull captures the creativity-stifling effect of overplanning:

If you seek to plot out all your moves before you make them – if you put your faith in slow, deliberative planning in the hopes it will spare you failure down the line – well, you're deluding yourself. For one thing, it's easier to plan derivative work – things that copy or repeat something already out there. So if your primary goal is to have a fully worked out, set-in-stone plan, you are only upping your chances of being unoriginal. Moreover, you cannot plan your way out of problems. While planning is very important, and we do a lot of it, there is only so much you can control in a creative environment. In general, I have found that people who pour their energy into thinking about an approach and insisting that it is too early to act are wrong just as often as people who dive in and work quickly. The overplanners just take longer to be wrong (and, when things inevitably go awry, are more crushed by the feeling that they have failed). There's a corollary to this, as well: The more time you spend mapping out an approach, the more likely you are to get attached to it. The nonworking idea gets worn into your brain, like a rut in the mud. It can be difficult to get free of it and head in a different direction. Which, more often than not, is exactly what you must do.

If you seek to plot out all your moves before you make them – if you put your faith in slow, deliberative planning in the hopes it will spare you failure down the line – well, you're deluding yourself. For one thing, it's easier to plan derivative work – things that copy or repeat something already out there. So if your primary goal is to have a fully worked out, set-in-stone plan, you are only upping your chances of being unoriginal. Moreover, you cannot plan your way out of problems. While planning is very important, and we do a lot of it, there is only so much you can control in a creative environment. In general, I have found that people who pour their energy into thinking about an approach and insisting that it is too early to act are wrong just as often as people who dive in and work quickly. The overplanners just take longer to be wrong (and, when things inevitably go awry, are more crushed by the feeling that they have failed). There's a corollary to this, as well: The more time you spend mapping out an approach, the more likely you are to get attached to it. The nonworking idea gets worn into your brain, like a rut in the mud. It can be difficult to get free of it and head in a different direction. Which, more often than not, is exactly what you must do.

Color script for 'Up' from The Art of Pixar

With a sentiment that calls to mind David Foster Wallace's exquisite definition of leadership, Catmull concludes:

The antidote to fear is trust, and we all have a desire to find something to trust in an uncertain world. Fear and trust are powerful forces, and while they are not opposites, exactly, trust is the best tool for driving out fear. There will always be plenty to be afraid of, especially when you are doing something new. Trusting others doesn't mean that they won't make mistakes. It means that if they do (or if you do), you trust they will act to help solve it. Fear can be created quickly; trust can't. Leaders must demonstrate their trustworthiness, over time, through their actions – and the best way to do that is by responding well to failure.

The antidote to fear is trust, and we all have a desire to find something to trust in an uncertain world. Fear and trust are powerful forces, and while they are not opposites, exactly, trust is the best tool for driving out fear. There will always be plenty to be afraid of, especially when you are doing something new. Trusting others doesn't mean that they won't make mistakes. It means that if they do (or if you do), you trust they will act to help solve it. Fear can be created quickly; trust can't. Leaders must demonstrate their trustworthiness, over time, through their actions – and the best way to do that is by responding well to failure.

[…]

Rather than trying to prevent all errors, we should assume, as is almost always the case, that our people's intentions are good and that they want to solve problems. Give them responsibility, let the mistakes happen, and let people fix them. If there is fear, there is a reason – our job is to find the reason and to remedy it. Management's job is not to prevent risk but to build the ability to recover.

In the remainder of Creativity, Inc., Catmull goes on to explore the art of grappling with change and randomness, the role of honesty in innovation, and more, using Pixar's own becoming as a springboard for broader insights on the nature and secrets of creative success. Pair it with Sarah Lewis's indispensable exploration of creativity and the gift of failure.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

"Character – the willingness to accept responsibility for one's own life – is the source from which self-respect springs," Joan Didion wrote in her timeless meditation on self-respect. But how can character be cultivated in such a way as to foster that prized form of personal dignity, along with its sibling qualities of confidence and self-esteem?

"Character – the willingness to accept responsibility for one's own life – is the source from which self-respect springs," Joan Didion wrote in her timeless meditation on self-respect. But how can character be cultivated in such a way as to foster that prized form of personal dignity, along with its sibling qualities of confidence and self-esteem?

That's what celebrated artist, actor, playwright, and educator Anna Deavere Smith explores in a section of the altogether fantastic Letters to a Young Artist: Straight-up Advice on Making a Life in the Arts for Actors, Performers, Writers, and Artists of Every Kind (public library) – a compendium of counsel addressed to an imaginary young artist, titled after the famous Rilke tome, in which Smith addresses with equal parts pragmatic idealism and opinionated optimism those of us seeking change and championing social change, as well as those who see themselves as "one of the guardians of the human spirit." She introduces the premise, adding to history's most beautiful definitions of art:

Art should take what is complex and render it simply. It takes a lot of skill, human understanding, stamina, courage, energy, and heart to do that. It takes, most of all, what a great scholar of artists and educators, Maxine Greene, calls "wide-awakeness" to do that. I am interested in the artist who is awake, or who wants desperately to wake up.

Art should take what is complex and render it simply. It takes a lot of skill, human understanding, stamina, courage, energy, and heart to do that. It takes, most of all, what a great scholar of artists and educators, Maxine Greene, calls "wide-awakeness" to do that. I am interested in the artist who is awake, or who wants desperately to wake up.

[…]

I am trying to make a call, with this book, to you young brave hearts who would like to find new collaborations with scholars, with businesspeople, with human rights workers, with scientists, and more, to make art that seeks to study and inform the human condition: art that is meaningful.

For artists and creative spirits alike, Smith argues, the issue of confidence is as important as it is messy – and it's also often a placeholder term for something far more crucial in the dogged pursuit of mastery that defines any successful creative endeavor. She writes:

Confidence is a static state. Determination is active. Determination allows for doubt and for humility – both of which are critical in the world today. There is so much that we don't know, and so much that we know we don't know. To be overly confident or without doubt seems silly to me.

Confidence is a static state. Determination is active. Determination allows for doubt and for humility – both of which are critical in the world today. There is so much that we don't know, and so much that we know we don't know. To be overly confident or without doubt seems silly to me.

Determination, on the other hand, is a commitment to win, a commitment to fight the good fight.

Equally important, and arguably even trickier to navigate, is the question of self-esteem – that elusive quality so vital to our spiritual flourishing yet, due to our human fallibility, so fragile amidst the world's constant and mostly unsolicited feedback and input. Smith reminds us that, not unlike the false validation of prestige, to peg our measure of self-worth on external validation is to commit ourselves to a never-ending cycle of disappointment – a seemingly simple observation that feels increasingly hard to internalize in our culture of "likes" and everyone's-a-critic commentary. Smith puts it elegantly:

In the arts, value … is like a yo-yo. You can't base your self-esteem on how well your work is selling or on how well it's received.

In the arts, value … is like a yo-yo. You can't base your self-esteem on how well your work is selling or on how well it's received.

Instead, she considers the essence of what self-esteem actually means and why it matters:

Self-esteem is that which gives us a feeling of well-being, a feeling that everything's going to be all right – that we can determine our own course and that we can travel that course. It's not that we travel the course alone, but we need the feeling of agency – that if everything were to fall apart, we could find a way to put things back together again.

Self-esteem is that which gives us a feeling of well-being, a feeling that everything's going to be all right – that we can determine our own course and that we can travel that course. It's not that we travel the course alone, but we need the feeling of agency – that if everything were to fall apart, we could find a way to put things back together again.

More than a form of self-soothing, however, self-esteem is also a powerful conduit for effecting change in the world:

Some people seem to be able to organize themselves around big ideas, and others cannot. This has to do with self-esteem. Self-esteem for creative people is important inasmuch as it is a part of what helps you organize yourself and others around an idea, so that it can come to fruition. Ideas are a dime a dozen; to make them real takes consistent, persistent application of energy toward that idea. Self-esteem is a foundation.

Some people seem to be able to organize themselves around big ideas, and others cannot. This has to do with self-esteem. Self-esteem for creative people is important inasmuch as it is a part of what helps you organize yourself and others around an idea, so that it can come to fruition. Ideas are a dime a dozen; to make them real takes consistent, persistent application of energy toward that idea. Self-esteem is a foundation.

While acknowledging, as modern psychology does, that the foundations of self-esteem itself are laid down during childhood, through our upbringing and our early experiences, Smith admonishes against relinquishing personal responsibility in the architecture of character and self-esteem, and reminds us that we are the sole custodians of our own center and worth:

Self-esteem cannot really be built from the outside. You begin to see the real evidence that you can, in fact, affect the things around you. These experiences ultimately integrate themselves inside – if that foundation is there. Self-esteem does not come from surrounding yourself with people and things that seem to increase your value. Real self-esteem is an integration of an inner value with things in the world around you.

Self-esteem cannot really be built from the outside. You begin to see the real evidence that you can, in fact, affect the things around you. These experiences ultimately integrate themselves inside – if that foundation is there. Self-esteem does not come from surrounding yourself with people and things that seem to increase your value. Real self-esteem is an integration of an inner value with things in the world around you.

It's about your worth. Your self-worth… You – and only you – can ultimately put the price tag on that. Your tag reveals not only how you value yourself, but how imaginative and original you are about valuing others. In my experience, happier people are people who have not only a high price tag on themselves, but a high price tag on the people around them – and the tags don't necessarily have to do with market value. They have to do with all the sense that adds up to human value.

Letters to a Young Artist is magnificent in its entirety, a precious invitation to communion with one of the most expansive and original creative spirits of our time. Complement it with Susan Sontag's illustrated insights on art, John Steinbeck on the creative spirit and the meaning of life, and Robert Henri on how the spirit of art binds us together.

Thanks, Wendy

:: MORE / SHARE ::

Hey bob sefcik! If you missed last week's edition – Kurt Vonnegut on kindness and community, the oldest living things in the world, meals from beloved books cooked and photographed, how a smile saved Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's life, and more – you can catch up

Hey bob sefcik! If you missed last week's edition – Kurt Vonnegut on kindness and community, the oldest living things in the world, meals from beloved books cooked and photographed, how a smile saved Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's life, and more – you can catch up

No comments:

Post a Comment