Hey bob sefcik! If you missed last week's edition – Paul Graham on how to make wealth, the science of our mental time travel and how it makes us human, Maya Angelou's beautiful letter to her younger self, how to get out of your own way and unblock the "spiritual electricity" of creative flow, and more – you can catch up right here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation – every little bit helps, and comes enormously appreciated.

Hey bob sefcik! If you missed last week's edition – Paul Graham on how to make wealth, the science of our mental time travel and how it makes us human, Maya Angelou's beautiful letter to her younger self, how to get out of your own way and unblock the "spiritual electricity" of creative flow, and more – you can catch up right here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation – every little bit helps, and comes enormously appreciated.

Much has been said about the difference between money and wealth and how we, as individuals, can make more of the latter, but the divergence between the two is arguably even more important the larger scale of nations and the global economy. What does it really mean to create wealth for people – for humanity – as opposed to money for governments and corporations?

Much has been said about the difference between money and wealth and how we, as individuals, can make more of the latter, but the divergence between the two is arguably even more important the larger scale of nations and the global economy. What does it really mean to create wealth for people – for humanity – as opposed to money for governments and corporations?

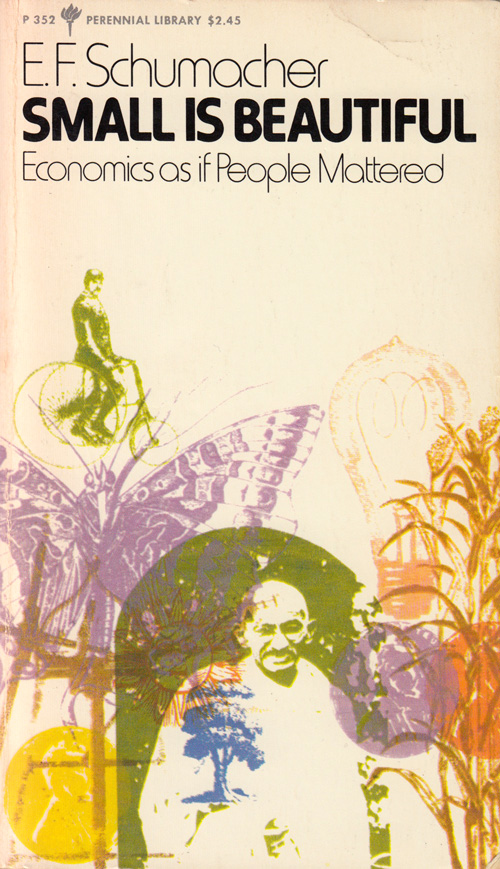

That's precisely what the influential German-born British economist, statistician, Rhodes Scholar, and economic theorist E. F. Schumacher explores in his seminal 1973 book Small Is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered (public library) – a magnificent collection of essays at the intersection of economics, ethics, and environmental awareness, which earned Schumacher the prestigious Prix Européen de l'Essai Charles Veillon award and was deemed by The Times Literary Supplement one of the 100 most important books published since WWII. Sharing an ideological kinship with such influential minds as Tolstoy and Gandhi, Schumacher's is a masterwork of intelligent counterculture, applying history's deepest, most timeless wisdom to the most pressing issues of modern life in an effort to educate, elevate and enlighten.

One of the most compelling essays in the book, titled "Buddhist Economics," applies spiritual principles and moral purpose to the question of wealth. Writing around the same time that Alan Watts considered the subject, Schumacher begins:

"Right Livelihood" is one of the requirements of the Buddha's Noble Eightfold Path. It is clear, therefore, that there must be such a thing as Buddhist economics… Spiritual health and material well-being are not enemies: they are natural allies.

"Right Livelihood" is one of the requirements of the Buddha's Noble Eightfold Path. It is clear, therefore, that there must be such a thing as Buddhist economics… Spiritual health and material well-being are not enemies: they are natural allies.

Traditional Western economics, Schumacher argues, is bedeviled a self-righteousness of sorts that blinds us to this fact – a fundamental fallacy that considers "goods as more important than people and consumption as more important than creative activity." He writes:

Economists themselves, like most specialists, normally suffer from a kind of metaphysical blindness, assuming that theirs is a science of absolute and invariable truths, without any presuppositions. Some go as far as to claim that economic laws are as free from "metaphysics" or "values" as the law of gravitations.

Economists themselves, like most specialists, normally suffer from a kind of metaphysical blindness, assuming that theirs is a science of absolute and invariable truths, without any presuppositions. Some go as far as to claim that economic laws are as free from "metaphysics" or "values" as the law of gravitations.

From this stems our chronic desire to avoid work and the difficulty of finding truly fulfilling work that aligns with our sense of purpose. Schumacher paints the backdrop for the modern malady overwork:

There is universal agreement that a fundamental source of wealth is human labor. Now, the modern economists has been brought up to consider "labor" or work as little more than a necessary evil. From the point of view of the employer, it is in any case simply an item of cost, to be reduced to a minimum if it cannot be eliminated altogether, say, by automation. From the point of view of the workman, it is a "disutility"; to work is to make a sacrifice of one's leisure and comfort, and wages are a kind of compensation for the sacrifice. Hence the ideal from the point of view of the employer is to have output without employees, and the ideal from the point of view of the employee is to have income without employment.

There is universal agreement that a fundamental source of wealth is human labor. Now, the modern economists has been brought up to consider "labor" or work as little more than a necessary evil. From the point of view of the employer, it is in any case simply an item of cost, to be reduced to a minimum if it cannot be eliminated altogether, say, by automation. From the point of view of the workman, it is a "disutility"; to work is to make a sacrifice of one's leisure and comfort, and wages are a kind of compensation for the sacrifice. Hence the ideal from the point of view of the employer is to have output without employees, and the ideal from the point of view of the employee is to have income without employment.

The consequences of these attitudes both in theory and in practice are, of course, extremely far-reaching. If the ideal with regard to work is to get rid of it, every method that "reduces the work load" is a good thing. The most potent method, short of automation, is the so-called "division of labor"… Here it is not a matter of ordinary specialization, which mankind has practiced from time immemorial, but of dividing up every complete process of production into minute parts, so that the final product can be produced at great speed without anyone having had to contribute more than a totally insignificant and, in most cases, unskilled movement of his limbs.

Schumacher contrasts this with the Buddhist perspective:

The Buddhist point of view takes the function of work to be at least threefold: to give a man a chance to utilize and develop his faculties; to enable him to overcome his ego-centeredness by joining with other people in a common task; and to bring forth the goods and services needed for a becoming existence. Again, the consequences that flow from this view are endless. To organize work in such a manner that it becomes meaningless, boring, stultifying, or nerve-racking for the worker would be little short of criminal; it would indicate a greater concern with goods than with people, an evil lack of compassion and a soul-destroying degree of attachment to the most primitive side of this worldly existence. Equally, to strive for leisure as an alternative to work would be considered a complete misunderstanding of one of the basic truths of human existence, namely that work and leisure are complementary parts of the same living process and cannot be separated without destroying the joy of work and the bliss of leisure.

The Buddhist point of view takes the function of work to be at least threefold: to give a man a chance to utilize and develop his faculties; to enable him to overcome his ego-centeredness by joining with other people in a common task; and to bring forth the goods and services needed for a becoming existence. Again, the consequences that flow from this view are endless. To organize work in such a manner that it becomes meaningless, boring, stultifying, or nerve-racking for the worker would be little short of criminal; it would indicate a greater concern with goods than with people, an evil lack of compassion and a soul-destroying degree of attachment to the most primitive side of this worldly existence. Equally, to strive for leisure as an alternative to work would be considered a complete misunderstanding of one of the basic truths of human existence, namely that work and leisure are complementary parts of the same living process and cannot be separated without destroying the joy of work and the bliss of leisure.

From the Buddhist point of view, there are therefore two types of mechanization which must be clearly distinguished: one that enhances a man's skill and power and one that turns the work of man over to a mechanical slave, leaving man in a position of having to serve the slave.

E.F. Schumacher

With an undertone of Gandhi's timeless words, Schumacher writes:

Buddhist economics must be very different from the economics of modern materialism, since the Buddhist sees the essence of civilization not in a multiplication of wants but in the purification of human character. Character, at the same time, is formed primarily by a man's work. And work, properly conducted in conditions of human dignity and freedom, blesses those who do it and equally their products.

Buddhist economics must be very different from the economics of modern materialism, since the Buddhist sees the essence of civilization not in a multiplication of wants but in the purification of human character. Character, at the same time, is formed primarily by a man's work. And work, properly conducted in conditions of human dignity and freedom, blesses those who do it and equally their products.

But Schumacher takes care to point out that the Buddhist disposition, rather than a condemnation of the material world, is a more fluid integration with it:

While the materialist is mainly interested in goods, the Buddhist is mainly interested in liberation. But Buddhism is "The Middle Way" and therefore in no way antagonistic to physical well-being. It is not wealth that stands in the way of liberation but the attachment to wealth; not the enjoyment of pleasurable things but the craving for them. The keynote of Buddhist economics, therefore, is simplicity and non-violence. From an economist's point of view, the marvel of the Buddhist way of life is the utter rationality of its pattern – amazingly small means leading to extraordinarily satisfactory results.

While the materialist is mainly interested in goods, the Buddhist is mainly interested in liberation. But Buddhism is "The Middle Way" and therefore in no way antagonistic to physical well-being. It is not wealth that stands in the way of liberation but the attachment to wealth; not the enjoyment of pleasurable things but the craving for them. The keynote of Buddhist economics, therefore, is simplicity and non-violence. From an economist's point of view, the marvel of the Buddhist way of life is the utter rationality of its pattern – amazingly small means leading to extraordinarily satisfactory results.

This concept, Schumacher argues, is extremely difficult for an economist from a consumerist culture to grasp as we once again bump up against the warped Western prioritization of productivity over presence:

[The modern Western economist] is used to measuring the "standard of living" by the amount of annual consumption, assuming all the time that a man who consumes more is "better off" than a man who consumes less. A Buddhist economist would consider this approach excessively irrational: since consumption is merely a means to human well-being, the aim should be to obtain the maximum of well-being with the minimum of consumption…

[The modern Western economist] is used to measuring the "standard of living" by the amount of annual consumption, assuming all the time that a man who consumes more is "better off" than a man who consumes less. A Buddhist economist would consider this approach excessively irrational: since consumption is merely a means to human well-being, the aim should be to obtain the maximum of well-being with the minimum of consumption…

The ownership and the consumption of goods is a means to an end, and Buddhist economics is the systematic study of how to attain given ends with the minimum means.

[Western] economics, on the other hand, considers consumption to be the sole end and purpose of all economic activity, taking the factors of production – land, labor, and capital – as the means. the former, in short, tries to maximize human satisfactions by the optimal pattern of consumption, while the latter tries to maximize consumption by the optimal pattern of productive effort.

This maximization of "human satisfactions," Schumacher argues, is rooted in two intimately related Buddhist concepts – simplicity and non-violence:

The optimal pattern of consumption, producing a high degree of human satisfaction by means of a relatively low rate of consumption, allows people to live without great pressure and strain and to fulfill the primary injunctions of Buddhist teaching: "Cease to do evil; try to do good." As physical resources are everywhere limited, people satisfying their needs by means of a modest use of resources are obviously less likely to be at each other's throats than people depending upon a high rate of use. Equally, people who live in highly self-sufficient local communities are less likely to get involved in large-scale violence than people whose existence depends on worldwide systems of trade.

The optimal pattern of consumption, producing a high degree of human satisfaction by means of a relatively low rate of consumption, allows people to live without great pressure and strain and to fulfill the primary injunctions of Buddhist teaching: "Cease to do evil; try to do good." As physical resources are everywhere limited, people satisfying their needs by means of a modest use of resources are obviously less likely to be at each other's throats than people depending upon a high rate of use. Equally, people who live in highly self-sufficient local communities are less likely to get involved in large-scale violence than people whose existence depends on worldwide systems of trade.

Writing shortly after Rachel Carson's Silent Spring sparked the modern environmental movement, Schumacher presages the modern groundswell of advocacy for sustainable locally sourced products:

From the point of view of Buddhist economics … production from local resources for local needs is the most rational way of economic life, while dependence on imports from afar and the consequent need to produce for export to unknown and distant peoples is highly uneconomic and justifiable only in exceptional cases and on a small scale.

From the point of view of Buddhist economics … production from local resources for local needs is the most rational way of economic life, while dependence on imports from afar and the consequent need to produce for export to unknown and distant peoples is highly uneconomic and justifiable only in exceptional cases and on a small scale.

He concludes by framing the enduring value of a Buddhist approach to economics, undoubtedly even more urgently needed today than it was in 1973:

It is in the light of both immediate experience and long-term prospects that the study of Buddhist economics could be recommended even to those who believe that economic growth is more important than any spiritual or religious values. For it is not a question of choosing between "modern growth" and "traditional stagnation." It is a question of finding the right path to development, the Middle Way between materialist heedlessness and traditionalist immobility, in short, of finding "Right Livelihood."

It is in the light of both immediate experience and long-term prospects that the study of Buddhist economics could be recommended even to those who believe that economic growth is more important than any spiritual or religious values. For it is not a question of choosing between "modern growth" and "traditional stagnation." It is a question of finding the right path to development, the Middle Way between materialist heedlessness and traditionalist immobility, in short, of finding "Right Livelihood."

Small Is Beautiful is a superb read in its entirety. Complement it with Kurt Vonnegut on having enough and Thoreau on redefining success.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

On July 4, 1862, English mathematician and logician Charles Dodgson boarded a small boat with a few friends. Among them was a little girl named Alice Liddell. To entertain her and her sisters as they floated down the river between Oxford and Godstow, Dodgson fancied a whimsical story, which he'd come to publish three years later under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll. Alice in Wonderland went on to become one of the most beloved children's books of all time, and my all-time favorite.

In the century and a half since Sir John Tenniel's original illustrations, the Carroll classic has sprouted everything from a pop-up book adaptation to a witty cookbook to a quantum physics allegory, and hundreds of artists around the world have reimagined it with remarkable creative vision. After my recent highlights of the best illustrations for Tolkien's The Hobbit, here come the loveliest visual interpretations of the timeless book.

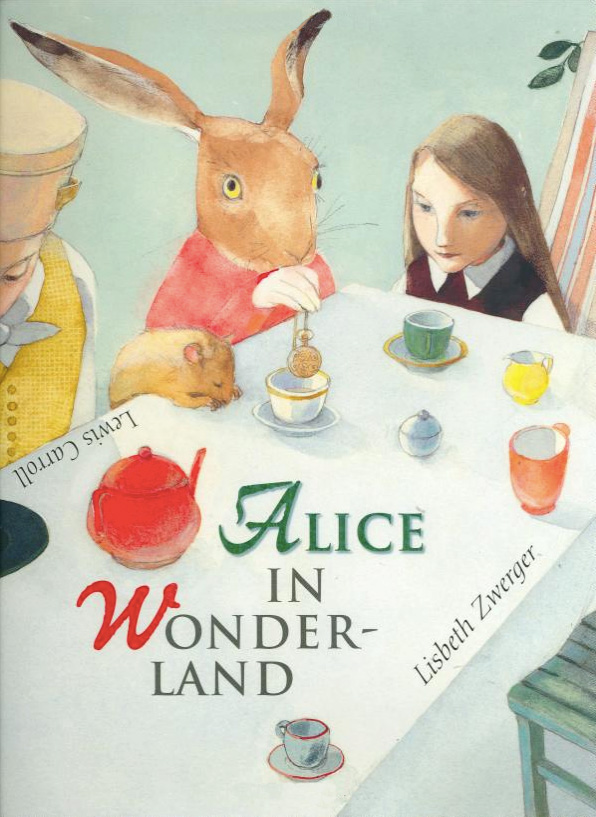

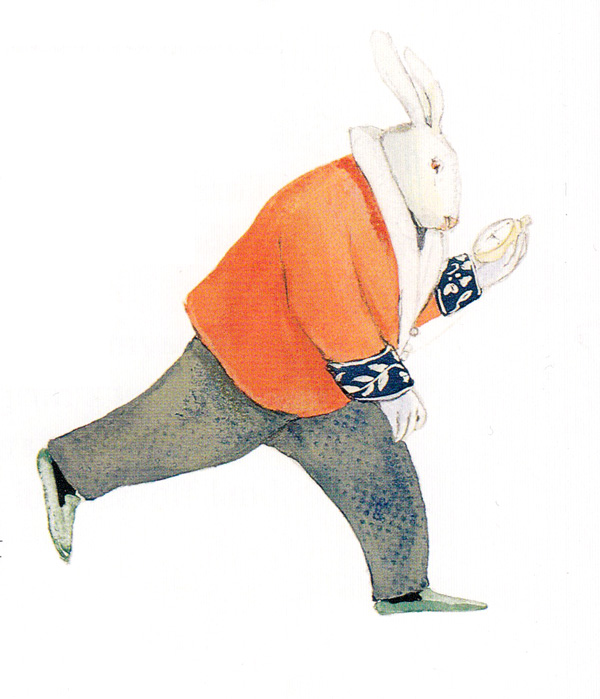

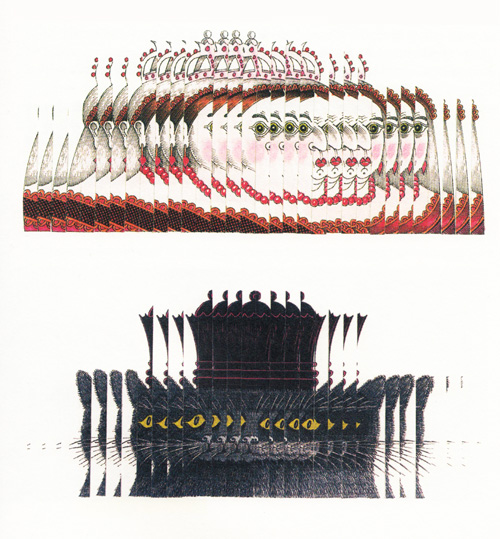

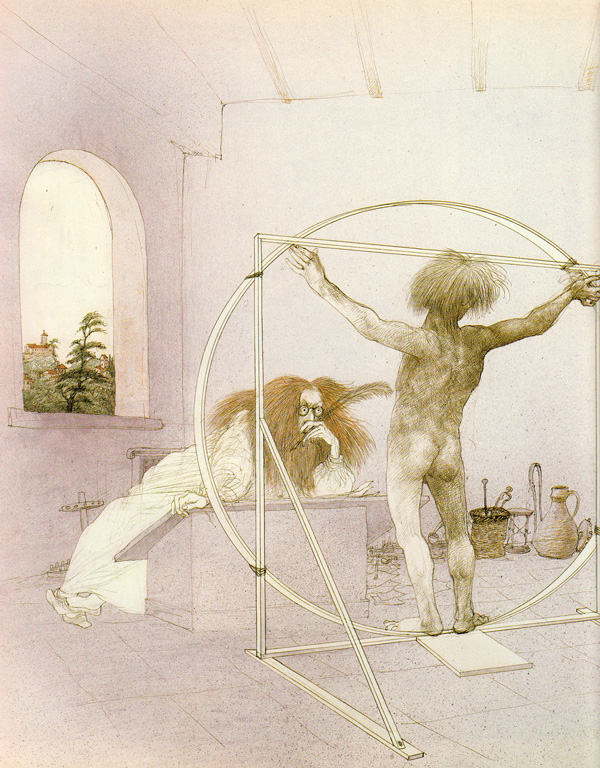

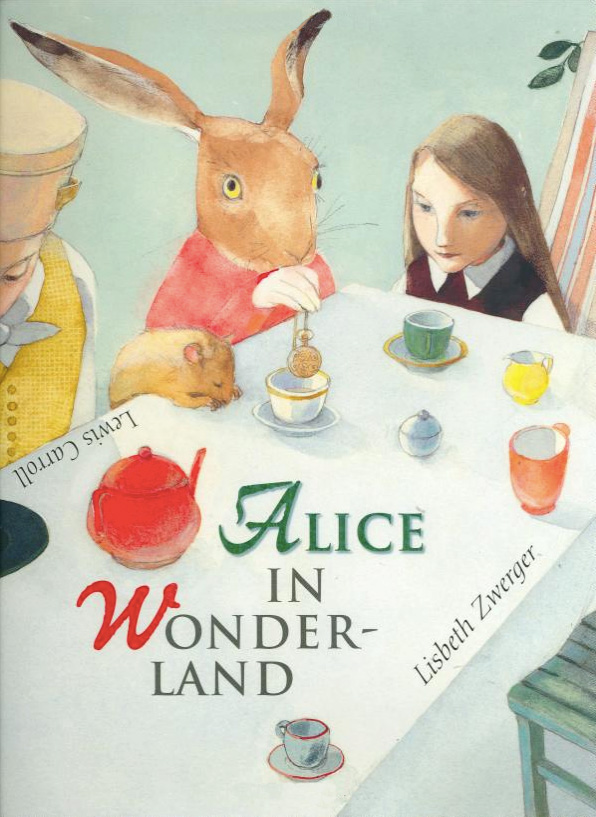

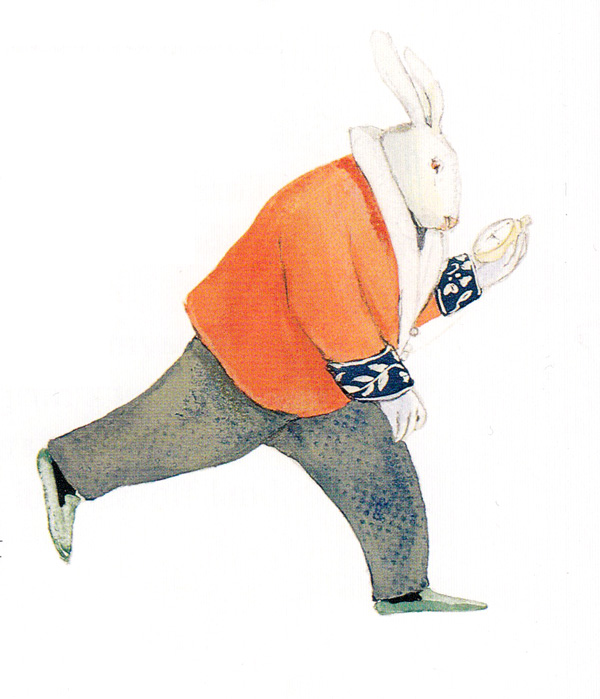

LISBETH ZWERGER (1999)

As an enormous admirer of Austrian artist Lisbeth Zwerger's creative vision – her illustrations for L. Frank Baum's The Wizard of Oz and Oscar Wilde's The Selfish Giant are absolutely enchanting – I was thrilled to track down a used copy of a sublime out-of-print edition of Alice in Wonderland (public library) featuring Zwerger's inventive, irreverent, and tenderly tantalizing drawings, published in 1999.

As an enormous admirer of Austrian artist Lisbeth Zwerger's creative vision – her illustrations for L. Frank Baum's The Wizard of Oz and Oscar Wilde's The Selfish Giant are absolutely enchanting – I was thrilled to track down a used copy of a sublime out-of-print edition of Alice in Wonderland (public library) featuring Zwerger's inventive, irreverent, and tenderly tantalizing drawings, published in 1999.

What makes Zwerger's aesthetic particularly bewitching is her ability render even the wildest feats of fancy in a soft and subdued style that tickles the imagination into animating the characters and scenes with life.

See more here.

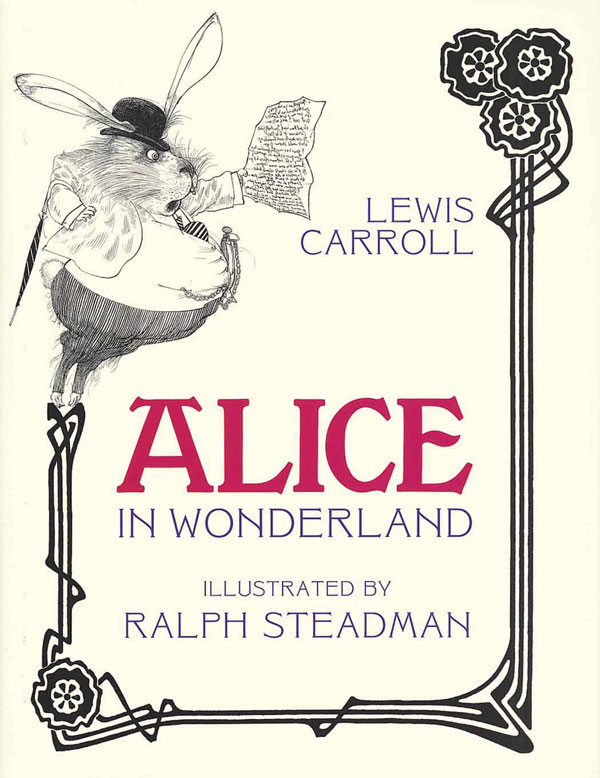

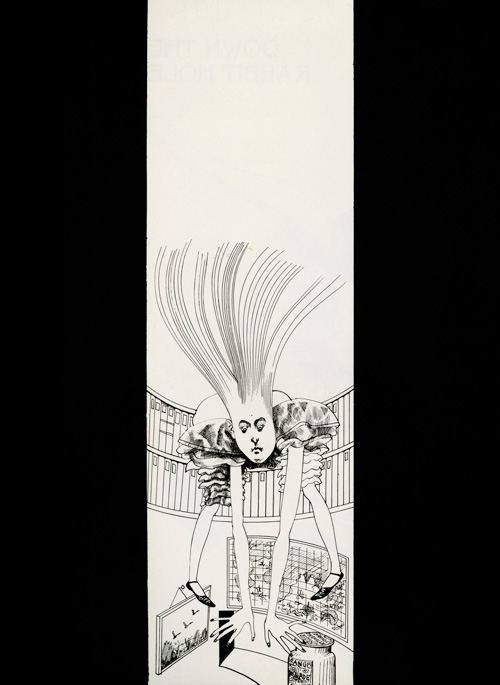

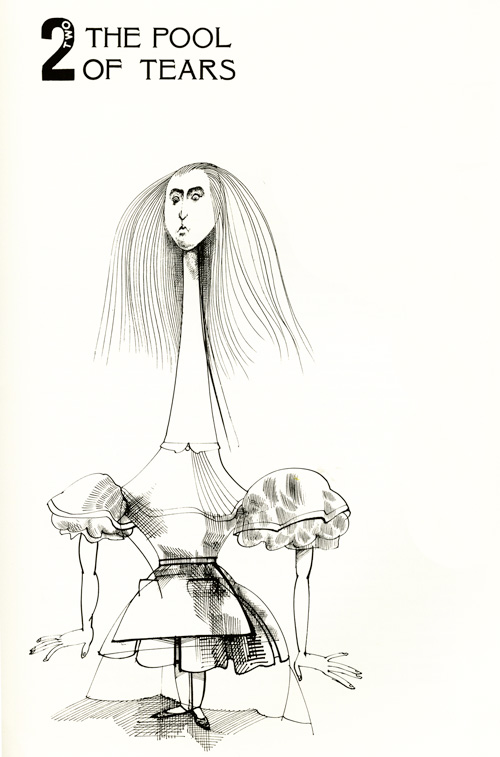

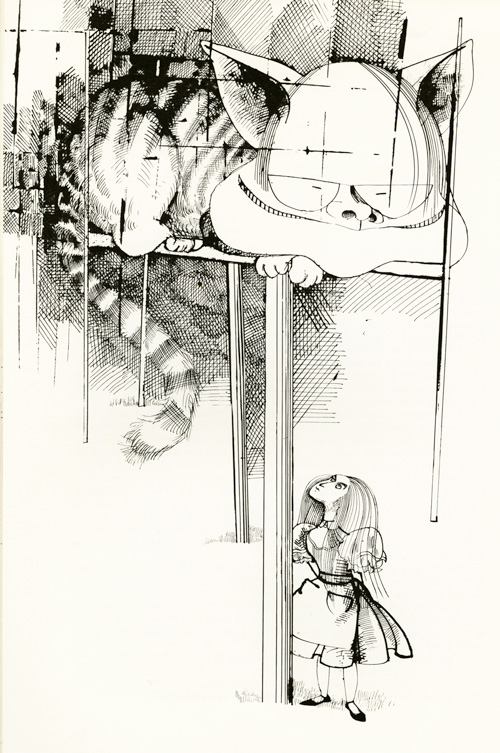

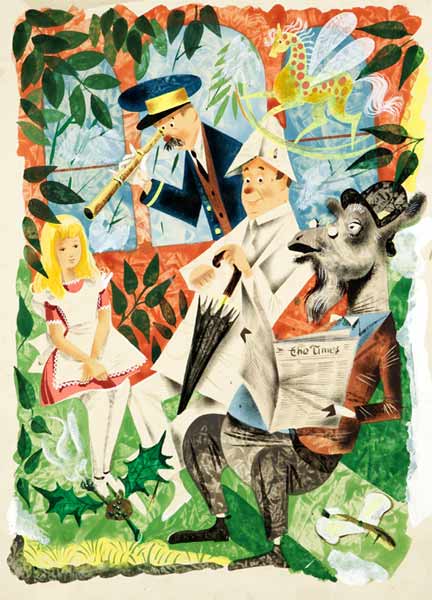

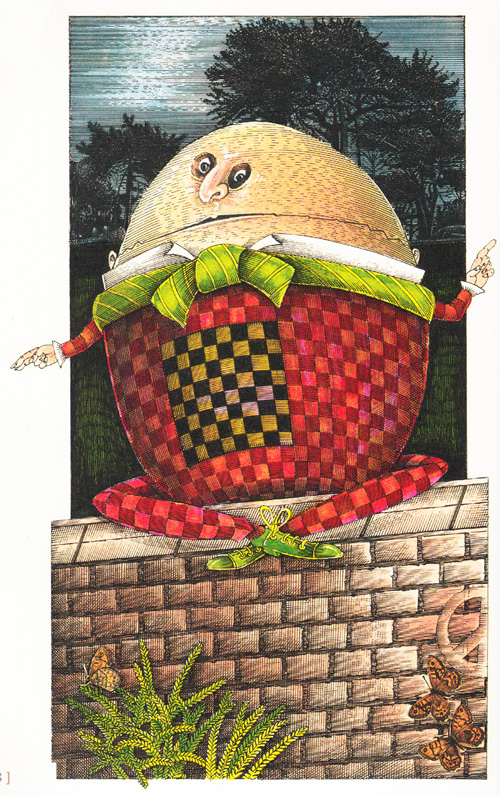

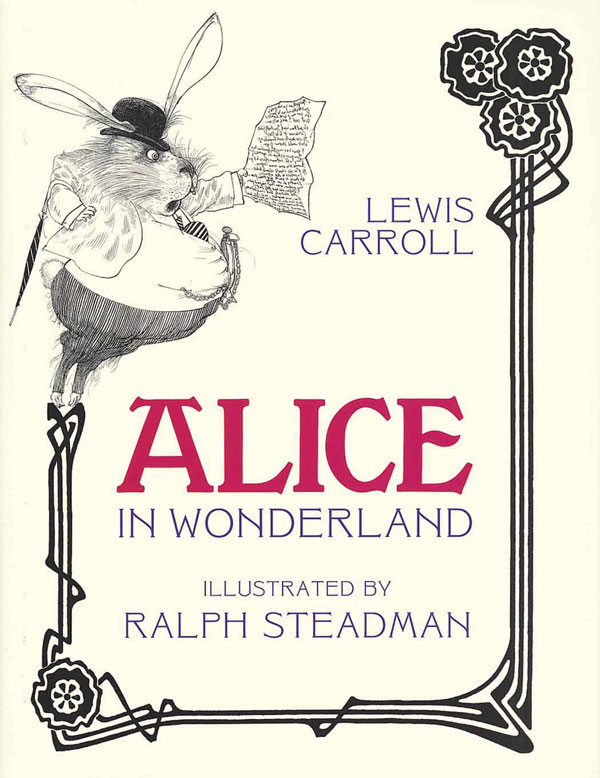

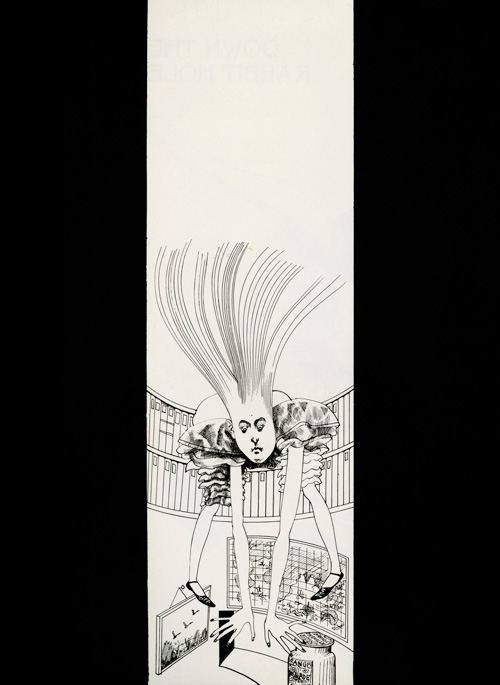

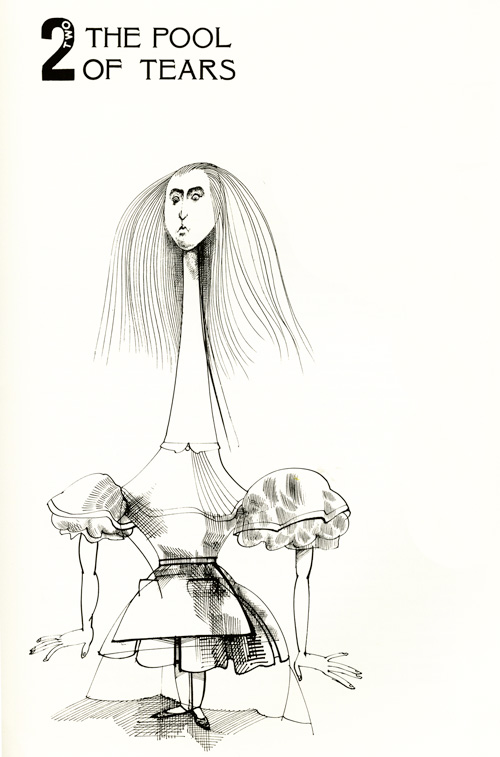

RALPH STEADMAN (1973)

Among the most singular and weirdly wonderful interpretations of the beloved story is the 1973 gem Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland Illustrated by Ralph Steadman (public library; Abe Books), more than twenty years before Steadman's spectacular illustrations for Orwell's Animal Farm. Barely in his mid-thirties at the time, the acclaimed British cartoonist – best-known today for his collaborations with Hunter S. Thompson and his unmistakable inkblot dog drawings – brings to the Carroll classic his singular semi-sensical visual genius, blending the irreverent with the sublime.

Among the most singular and weirdly wonderful interpretations of the beloved story is the 1973 gem Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland Illustrated by Ralph Steadman (public library; Abe Books), more than twenty years before Steadman's spectacular illustrations for Orwell's Animal Farm. Barely in his mid-thirties at the time, the acclaimed British cartoonist – best-known today for his collaborations with Hunter S. Thompson and his unmistakable inkblot dog drawings – brings to the Carroll classic his singular semi-sensical visual genius, blending the irreverent with the sublime.

See more here.

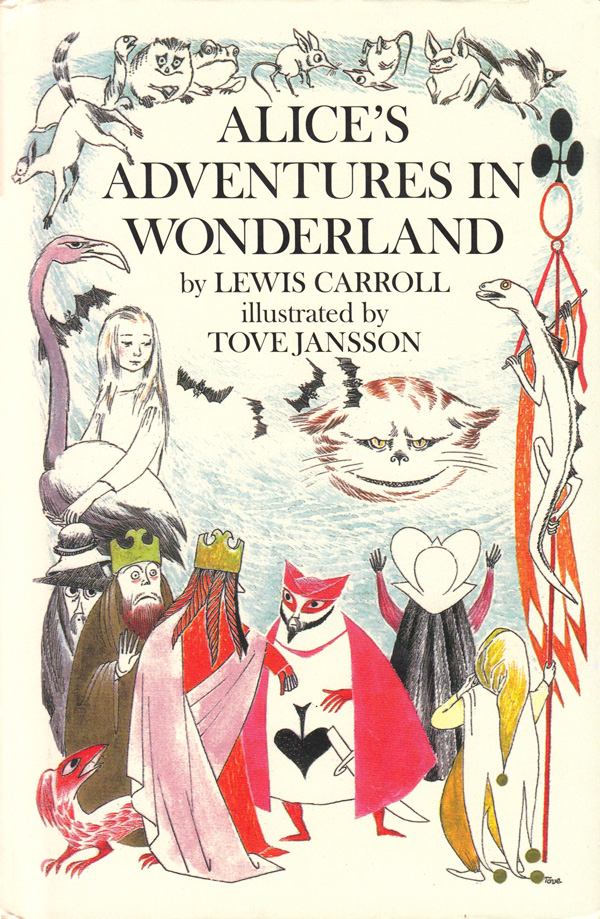

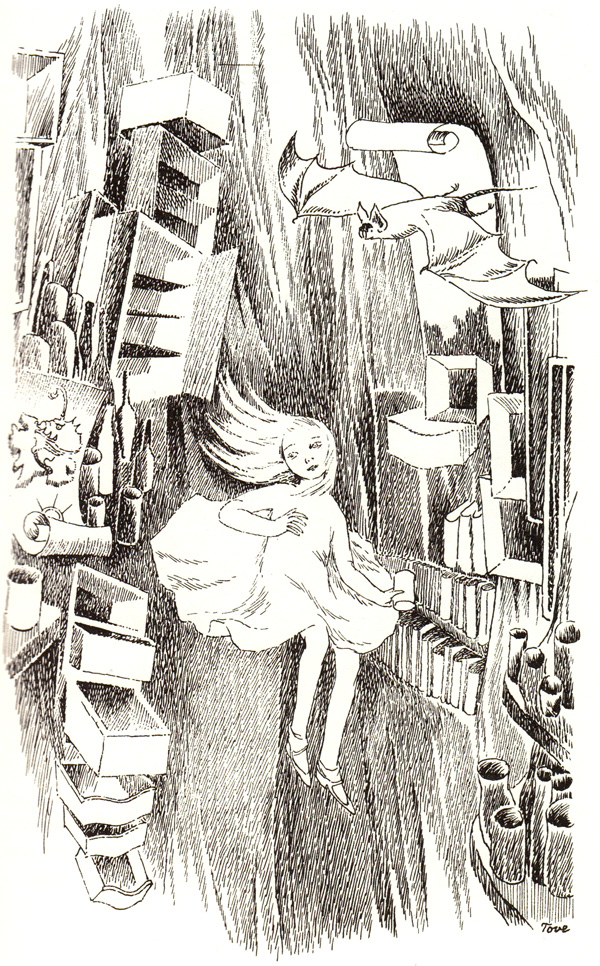

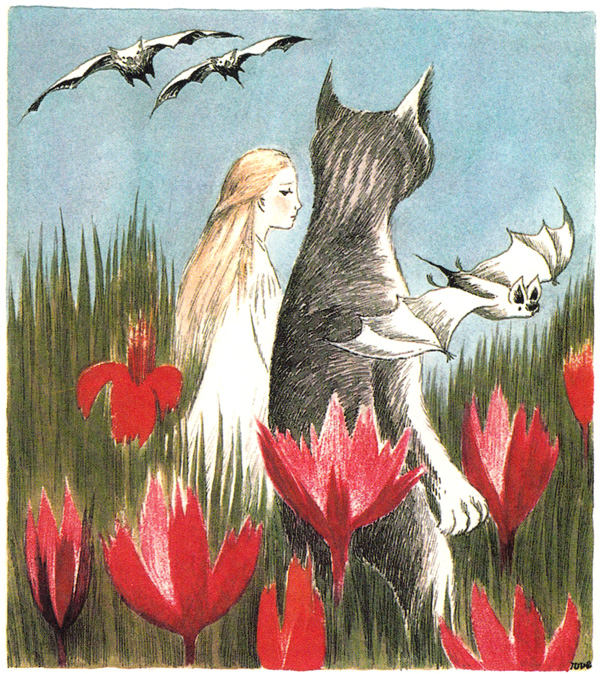

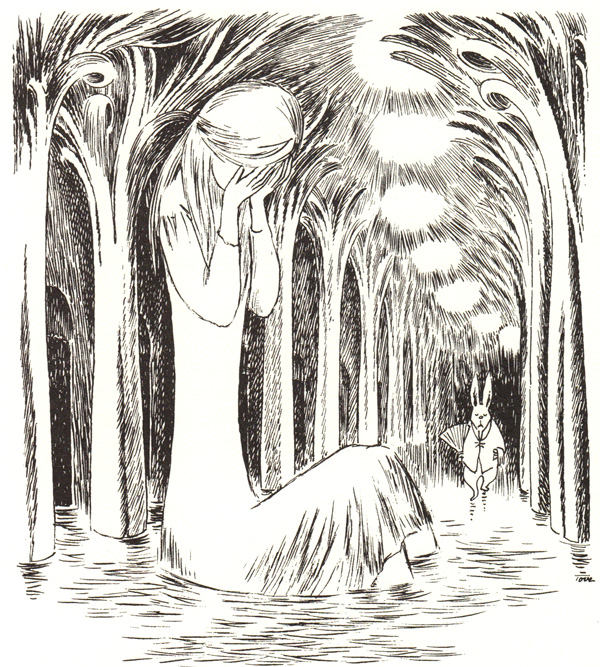

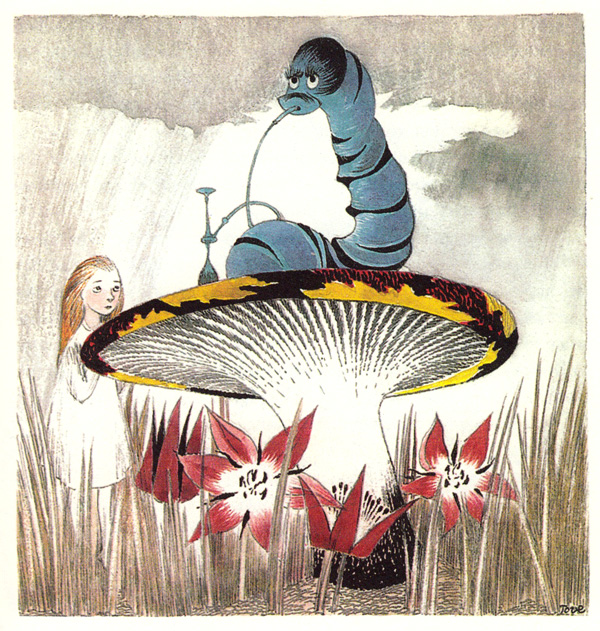

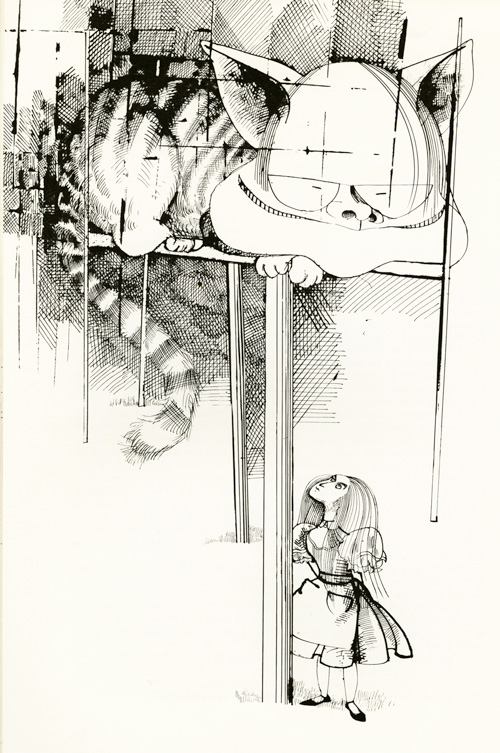

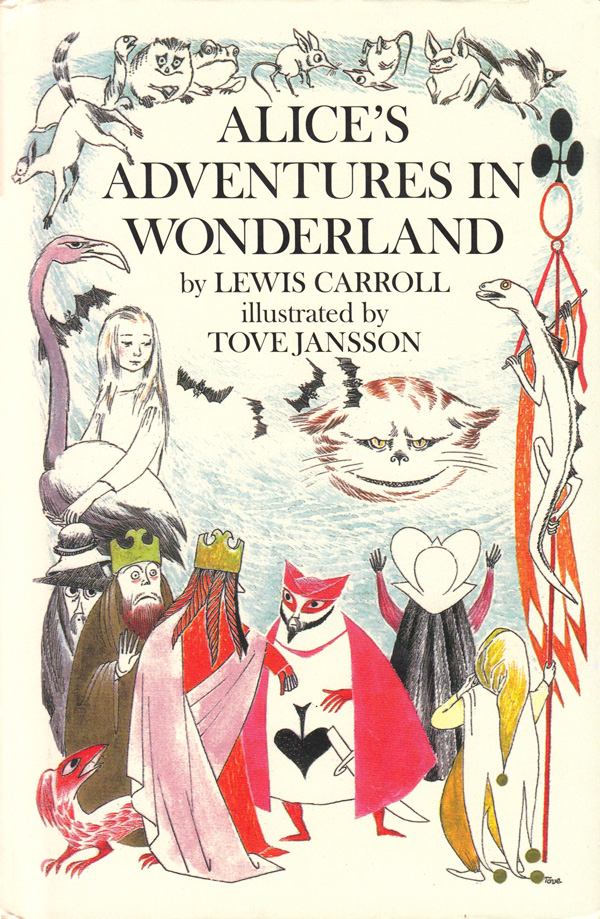

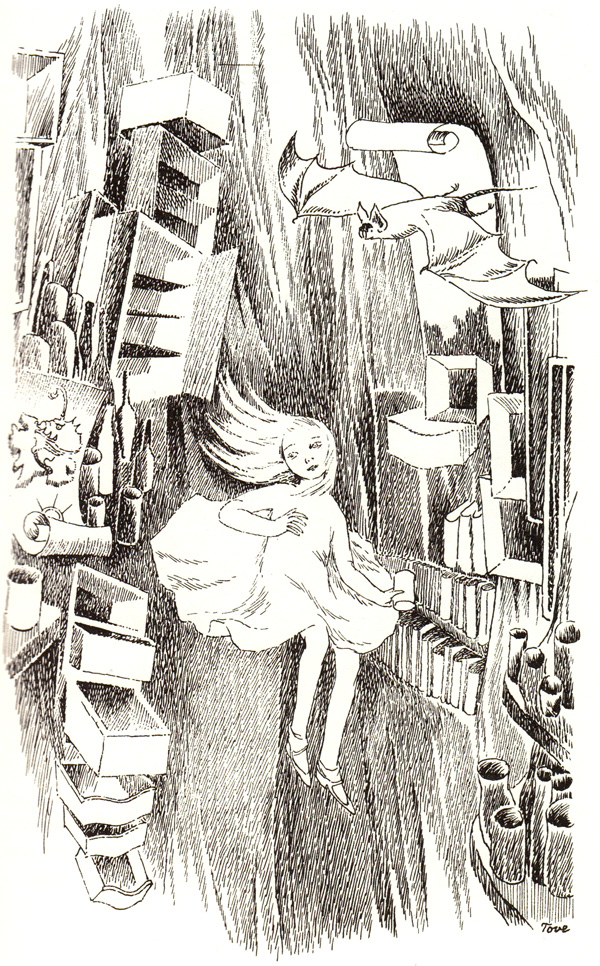

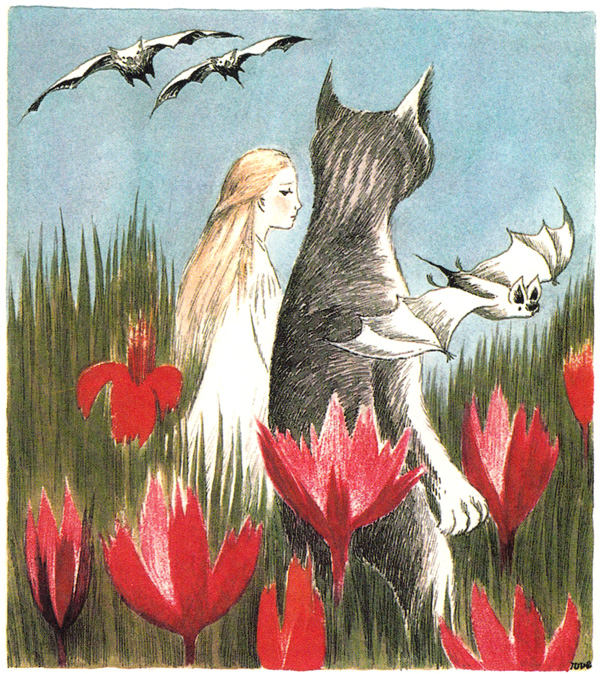

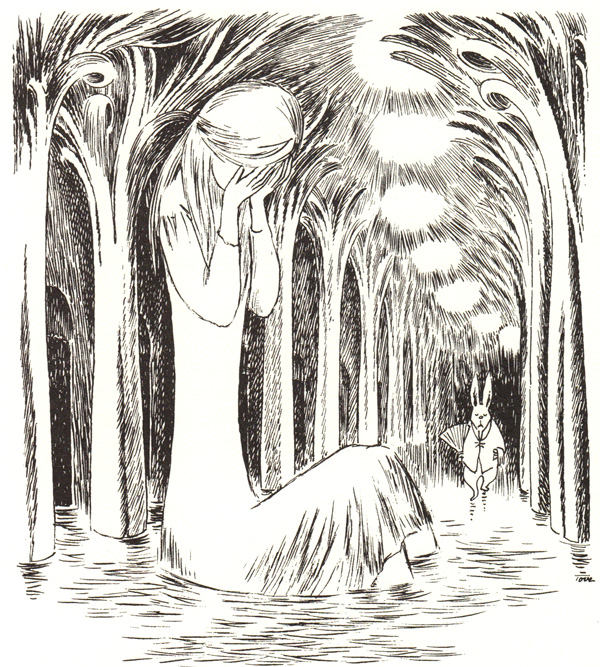

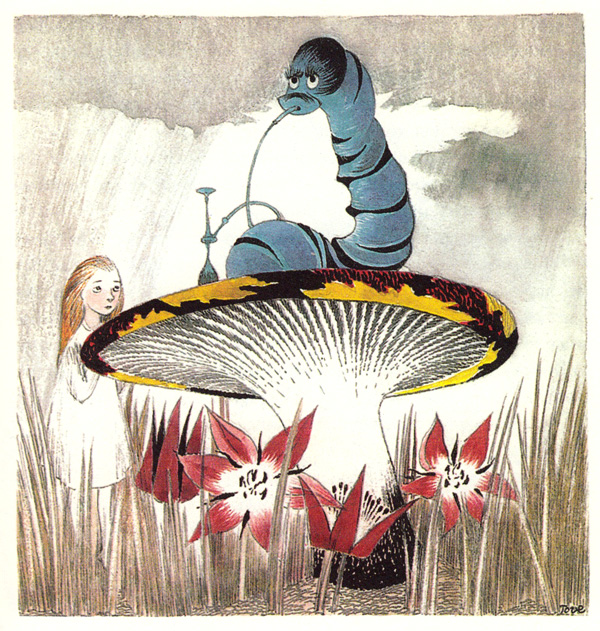

TOVE JANSSON (1966)

In 1959, three years before the publication of her gorgeous illustrations for The Hobbit and nearly two decades after her iconic Moomin characters were born, celebrated Swedish-speaking Finnish artist Tove Jansson was commissioned to illustrate a now-rare Swedish edition of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (public library), crafting a sublime fantasy experience that fuses Carroll's Wonderland with Jansson's Moomin Valley. The publisher, Åke Runnquist, thought Jansson would be a perfect fit for the project, as she had previously illustrated a Swedish translation of Carroll's The Hunting of the Snark – the 1874 book in which the word "snark" actually originated – at Runnquist's own request.

In 1959, three years before the publication of her gorgeous illustrations for The Hobbit and nearly two decades after her iconic Moomin characters were born, celebrated Swedish-speaking Finnish artist Tove Jansson was commissioned to illustrate a now-rare Swedish edition of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (public library), crafting a sublime fantasy experience that fuses Carroll's Wonderland with Jansson's Moomin Valley. The publisher, Åke Runnquist, thought Jansson would be a perfect fit for the project, as she had previously illustrated a Swedish translation of Carroll's The Hunting of the Snark – the 1874 book in which the word "snark" actually originated – at Runnquist's own request.

When Runnquist received her finished illustrations in the fall of 1966, he immediately fired off an excited telegram to Jansson: "Congratulations for Alice – you have produced a masterpiece." What an understatement.

See more here.

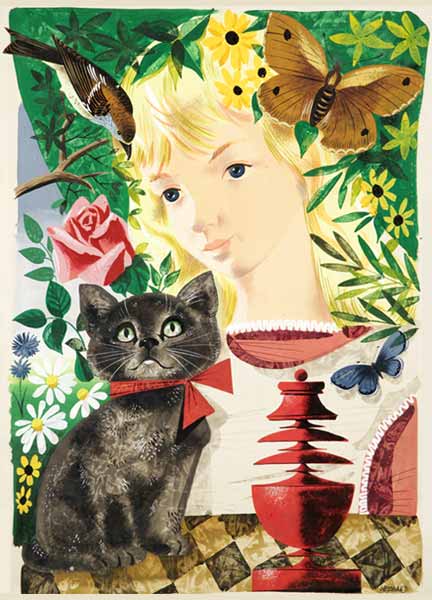

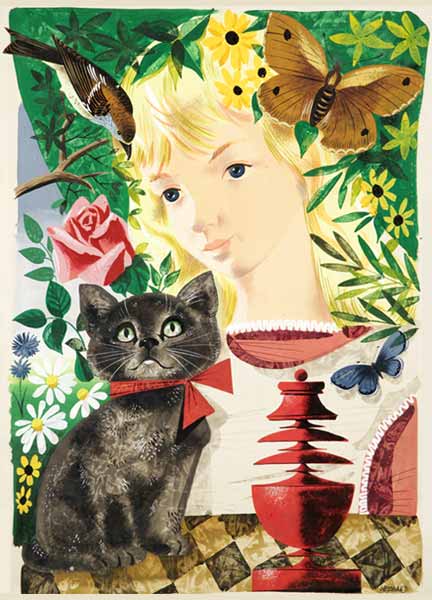

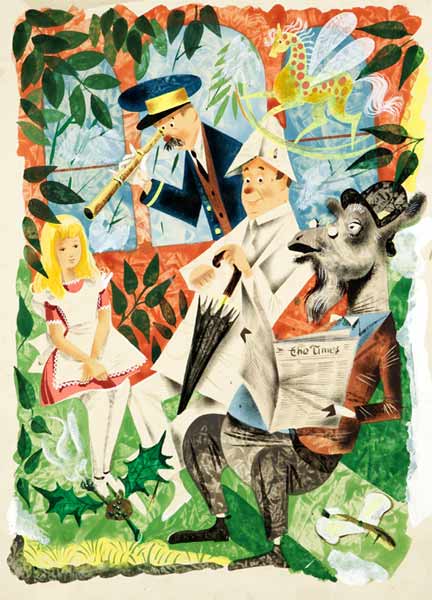

LEONARD WEISGARD (1949)

One of the most beautiful editions of the Carroll classic is also one of the earliest color ones – a glorious 1949 edition of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass (public library), illustrated by artist Leonard Weisgard. The vibrant, textured artwork exudes a certain mid-century boldness that makes it as much a timeless celebration of the iconic children's book as it is a time-capsule of bygone aesthetic from the golden age of illustration and graphic design.

See more here.

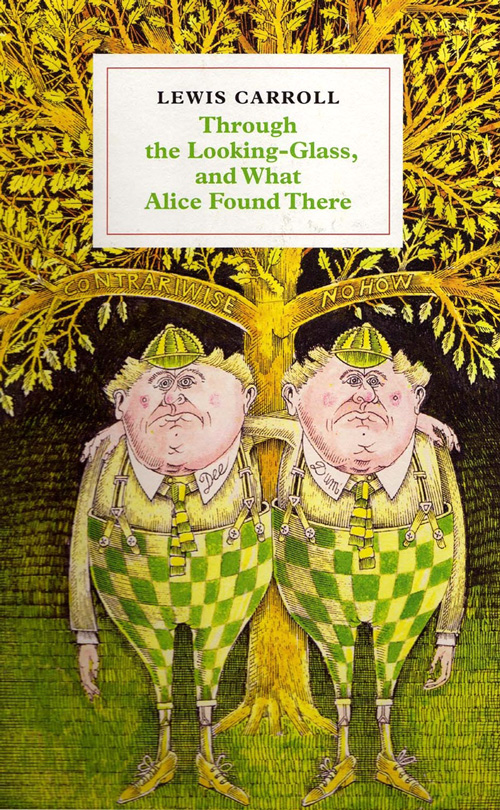

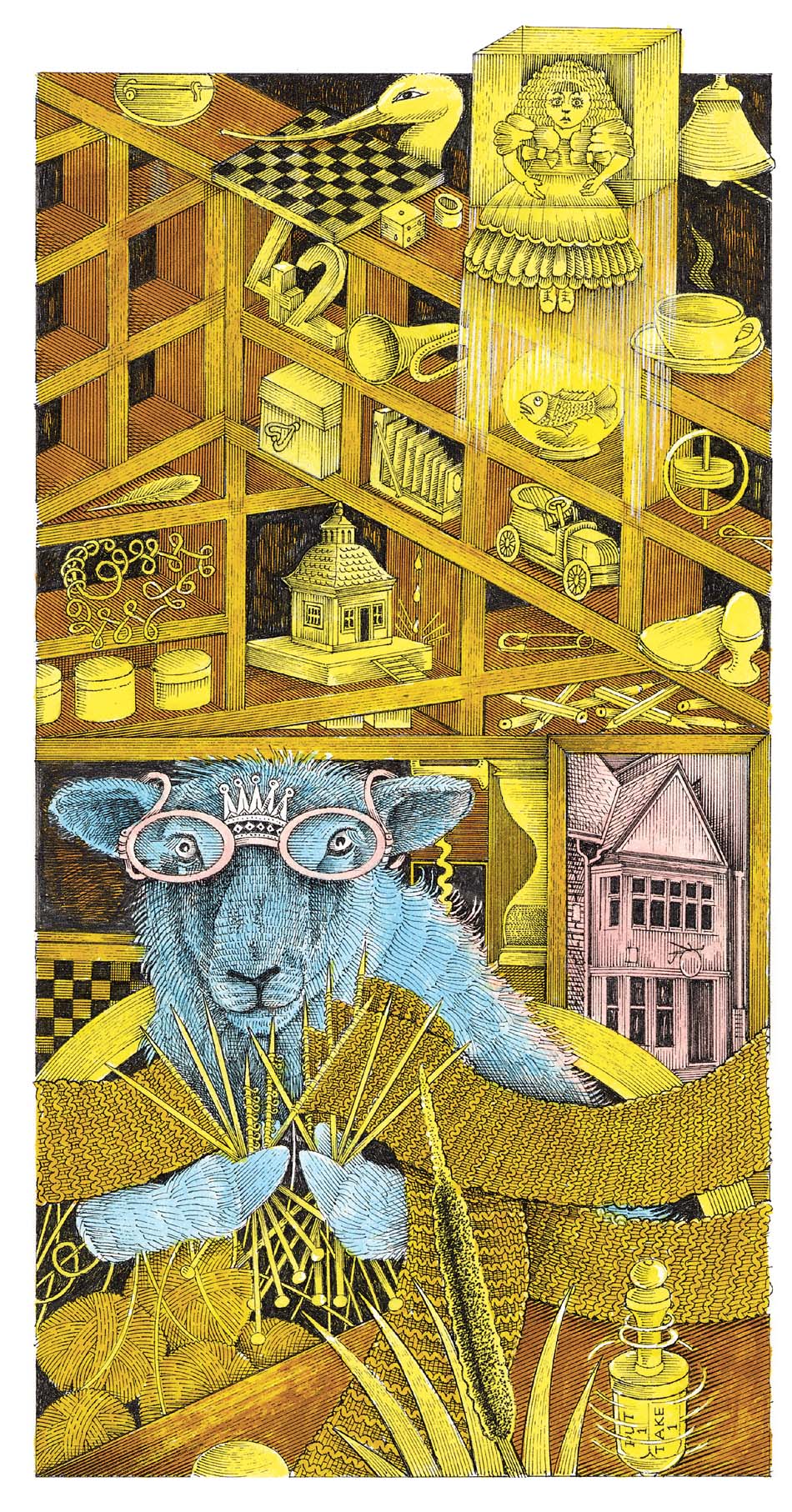

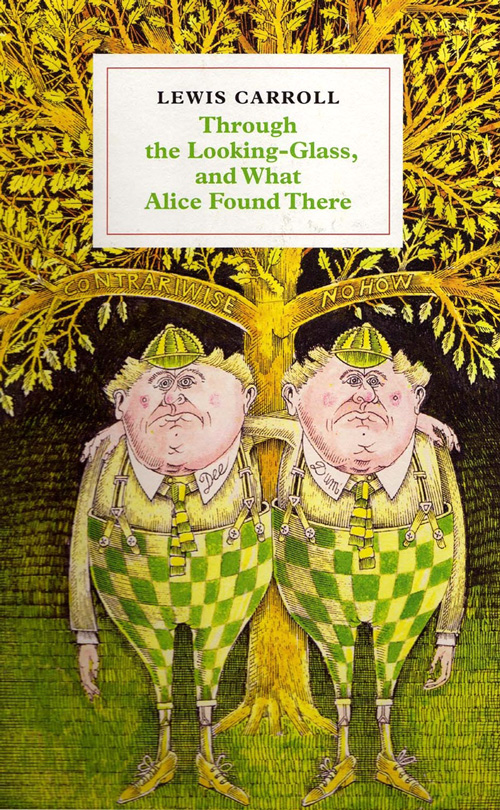

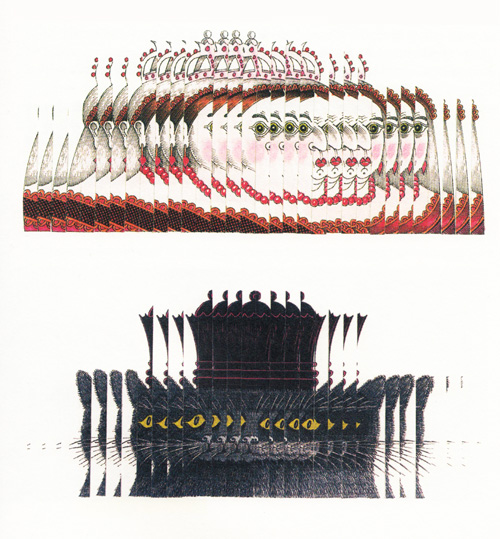

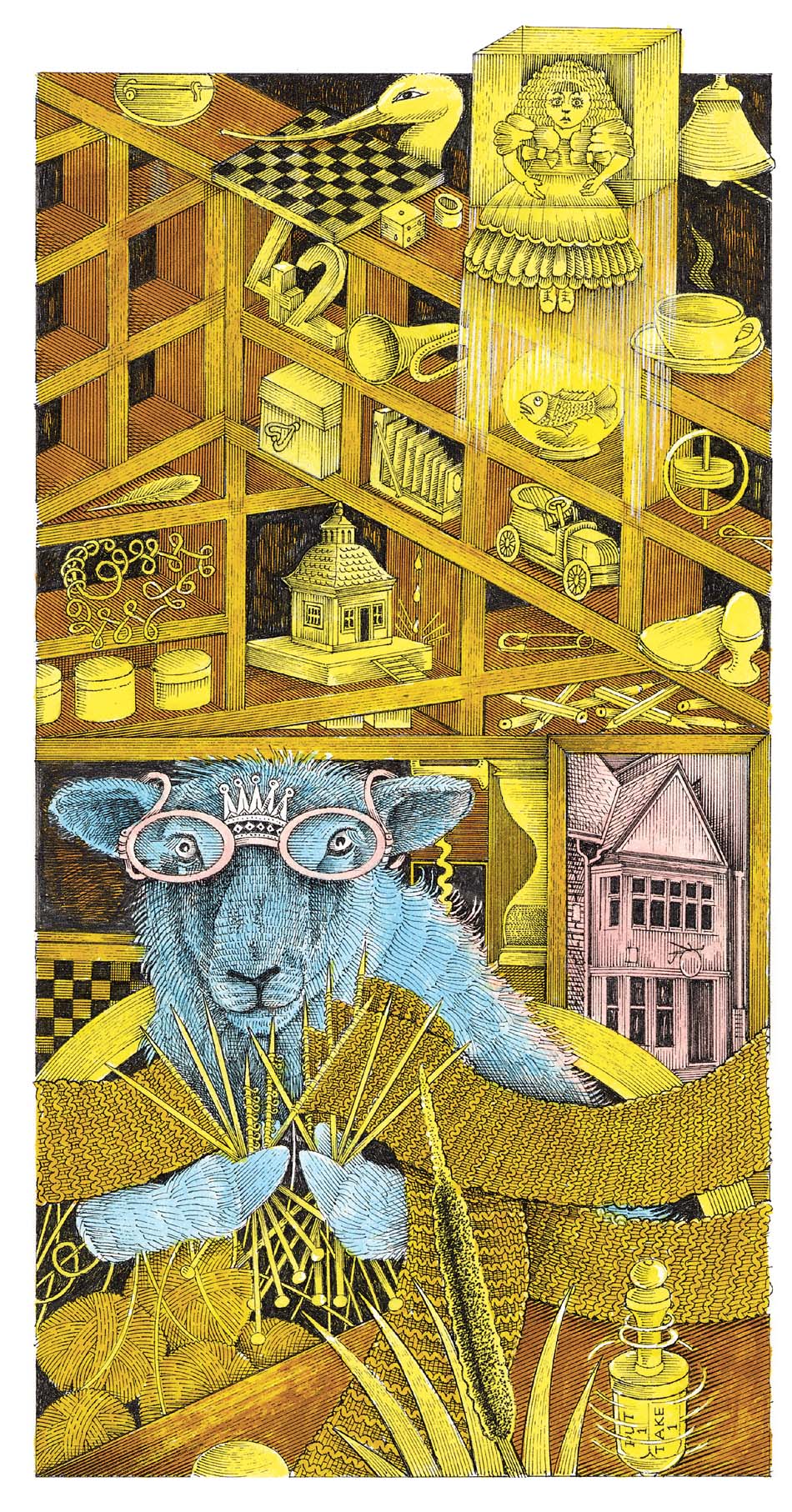

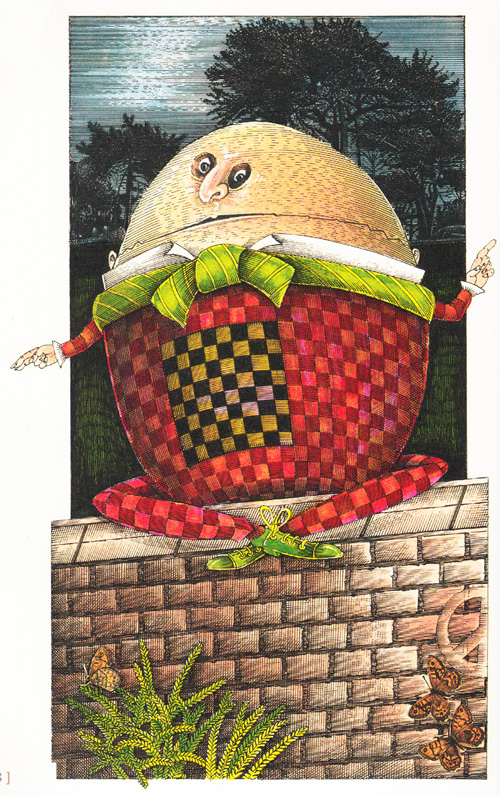

JOHN VERNON LORD (2011)

"Words mean more than we mean to express when we use them," Lewis Carroll once wrote in a letter to a friend, "so a whole book ought to mean a great deal more than the writer means."

"Words mean more than we mean to express when we use them," Lewis Carroll once wrote in a letter to a friend, "so a whole book ought to mean a great deal more than the writer means."

That's what British artist John Vernon Lord – one of the most imaginative literary illustrators working today, who also gave us those spectacular recent illustrations for James Joyce's Finnegans Wake – sought to embody in his special ultra-limited-edition Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There (public library), published in 2011 in a run of only 420 signed and numbered copies, of which 98 came with a special set of prints.

See more here.

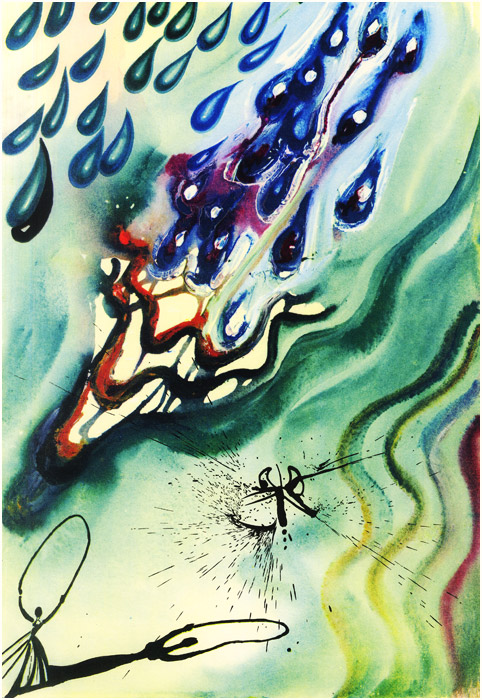

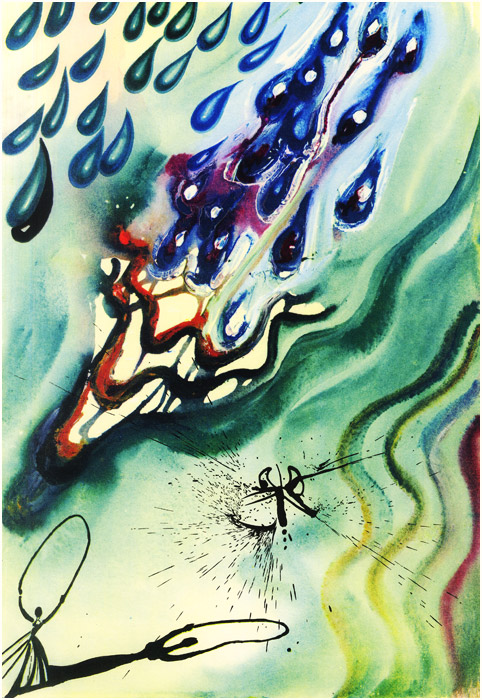

SALVADOR DALÍ (1969)

In 1969, Salvador Dalí was commissioned by New York's Maecenas Press-Random House to illustrate a special edition of the Carroll classic, consisting of 12 heliogravures – one for each chapter of the book and an original signed etching in four colors as the frontispiece. Distributed as the publisher's book of the month, the volume went on to become one of the most sought-after Dalí suites of all time – even rarer than Dalí's erotic vintage cookbook and his illustrations for Don Quixote, the essays of Montaigne, Romeo and Juliet, The Divine Comedy.

See more, including a hands-on video tour of the folio case, here.

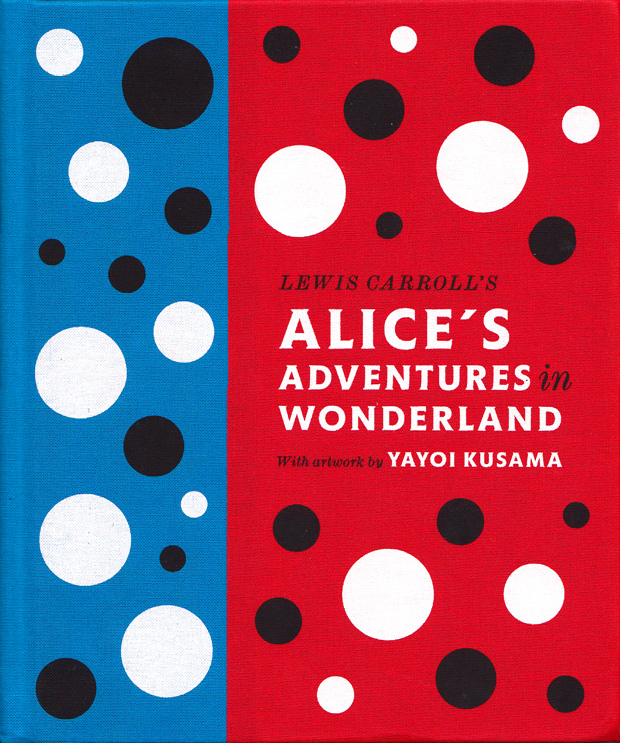

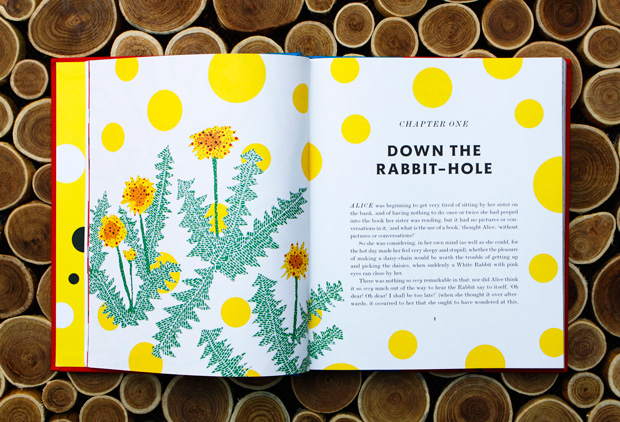

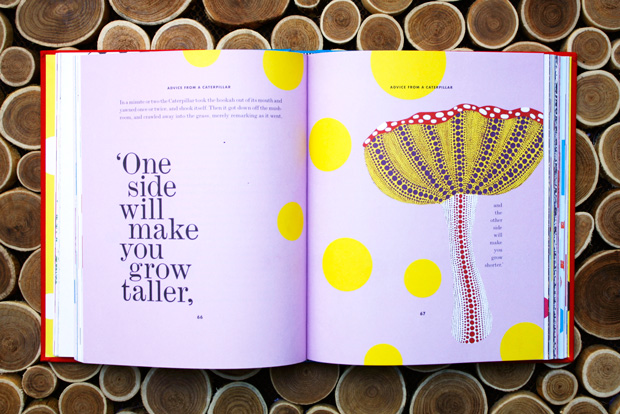

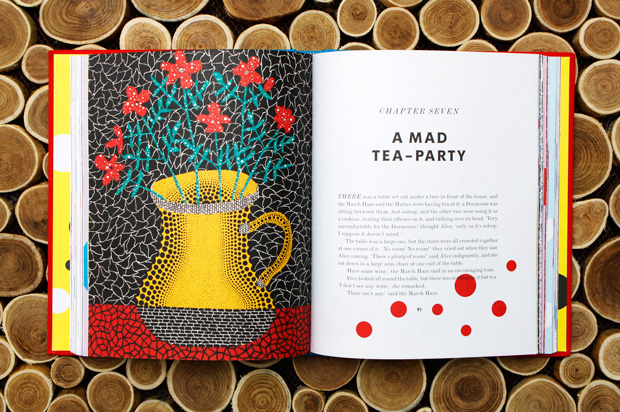

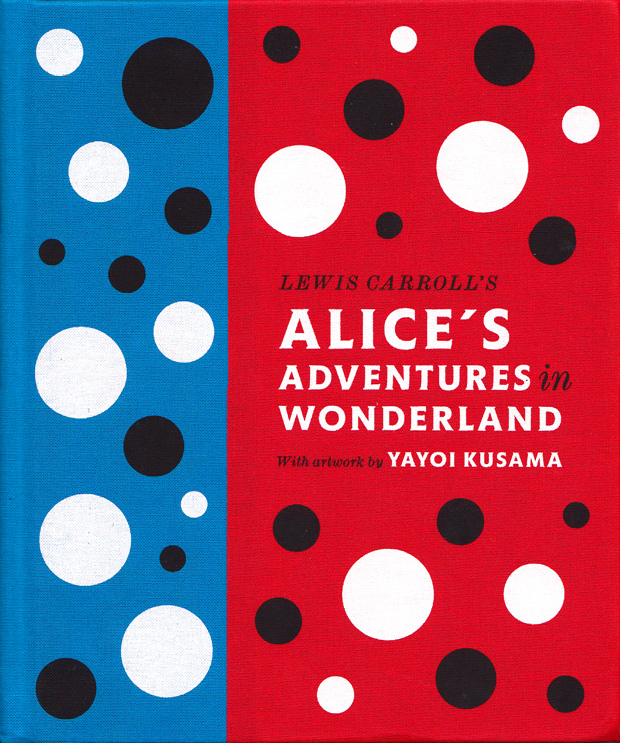

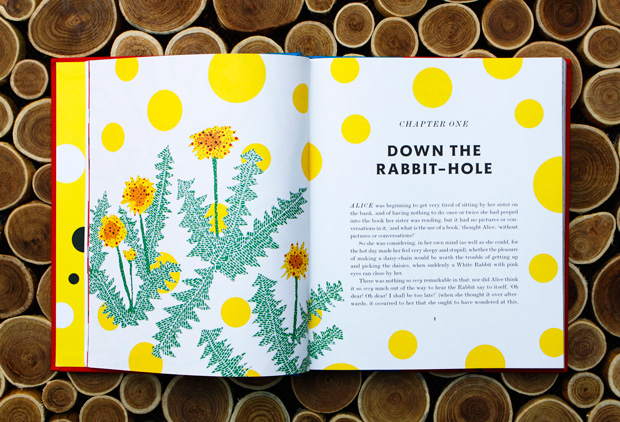

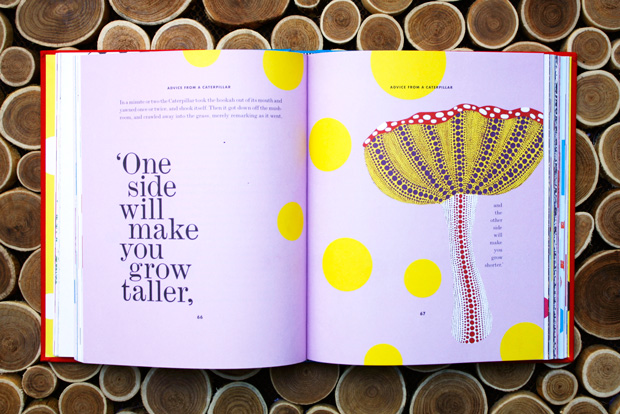

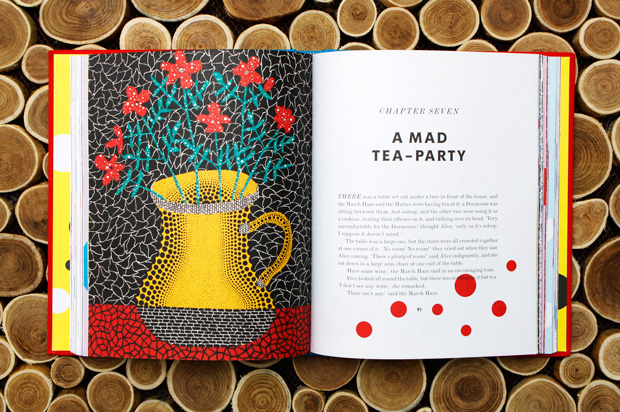

YAYOI KUSAMA (2012)

In 2012, Yayoi Kusama, Japan's most celebrated contemporary artist, unleashed her signature dotted magic onto a gorgeous edition of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (public library) from Penguin UK and book-designer-by-day, analog-data-visualization-artist-by-night Stefanie Posavec.

In 2012, Yayoi Kusama, Japan's most celebrated contemporary artist, unleashed her signature dotted magic onto a gorgeous edition of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (public library) from Penguin UK and book-designer-by-day, analog-data-visualization-artist-by-night Stefanie Posavec.

Since childhood, Kusama has had a rare condition that makes her see colorful spots on everything she looks at. Her vision, both literally and creatively, is thus naturally surreal, almost hallucinogenic. Her vibrant Alice artwork, sewn together in a magnificent fabric-bound hardcover tome, becomes an exquisite embodiment of Carroll's story and his fascination with the extraordinary way in which children see and explore the ordinary world.

See more, including a short trailer, here.

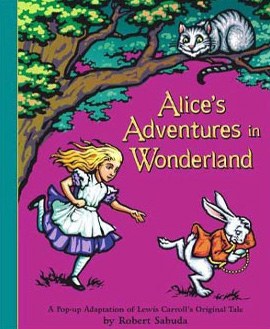

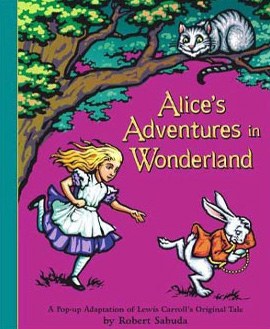

BONUS: ALICE IN WONDERLAND POP-UP BOOK (2003)

Those of us enchanted by imaginative pop-up books – from an adaptation of The Little Prince to the life of Leonardo da Vinci to a naughty Victoriana – are bound to fall in love with Alice's Adventures in Wonderland: A Pop-up Adaptation (public library) by pop-up book artist and paper engineer Robert Sabuda. Originally published in 2003 – three years after Sabuda's equally enchanting adaptation of The Wizard of Oz and five years before his take on Peter Pan – the book is a kind of "Victorian peep show" version of the Lewis Carroll classic.

Those of us enchanted by imaginative pop-up books – from an adaptation of The Little Prince to the life of Leonardo da Vinci to a naughty Victoriana – are bound to fall in love with Alice's Adventures in Wonderland: A Pop-up Adaptation (public library) by pop-up book artist and paper engineer Robert Sabuda. Originally published in 2003 – three years after Sabuda's equally enchanting adaptation of The Wizard of Oz and five years before his take on Peter Pan – the book is a kind of "Victorian peep show" version of the Lewis Carroll classic.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

"A writer," E.B. White asserted in a fantastic 1969 interview, "should tend to lift people up, not lower them down. Writers do not merely reflect and interpret life, they inform and shape life." A quarter century later, another literary titan articulated the same sentiment even more beautifully, a remarkable feat in my book, where dear old Elwyn Brooks reigns supreme.

"A writer," E.B. White asserted in a fantastic 1969 interview, "should tend to lift people up, not lower them down. Writers do not merely reflect and interpret life, they inform and shape life." A quarter century later, another literary titan articulated the same sentiment even more beautifully, a remarkable feat in my book, where dear old Elwyn Brooks reigns supreme.

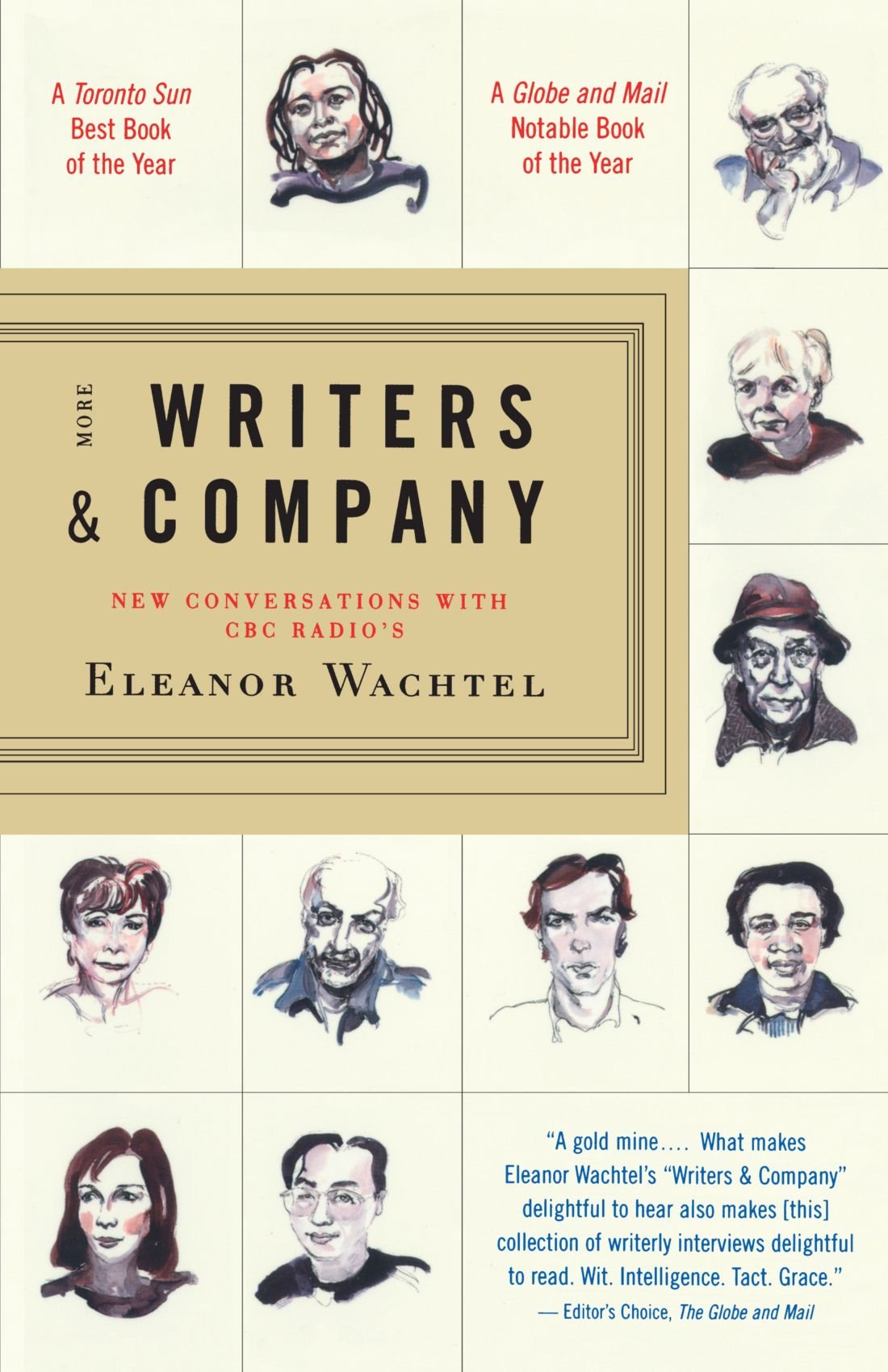

In a 1994 conversation with Canadian broadcaster Eleanor Wachtel, found in the altogether excellent More Writers & Company: New Conversations with CBC Radio's Eleanor Wachtel (public library), the great Nigerian novelist, poet, and critic Chinua Achebe (November 16, 1930–March 21, 2013) echoes White's wisdom with his own bend of poetic conviction – conviction all the more urgent in our age of increasingly despairing clickbait "journalism."

When Wachtel asks how the prominent South African writer and political activist Nadine Gordimer's description of Achebe as "a moralist and an idealist" has fared after years of political and personal struggle, he answers:

[My idealism is] still alive and well because without it the business of the writer would be meaningless. I don't think the world needs to be told stories of despair; there is enough despair as it is without anyone adding to it. If we have any role at all, I think it's the role of optimism, not blind or stupid optimism, but the kind which is meaningful, one that is rather close to that notion of the world which is not perfect, but which can be improved. In other words, we don't just sit and hope that things will work out; we have a role to play to make that come about. That seems to me to be the reason for the existence of the writer.

[My idealism is] still alive and well because without it the business of the writer would be meaningless. I don't think the world needs to be told stories of despair; there is enough despair as it is without anyone adding to it. If we have any role at all, I think it's the role of optimism, not blind or stupid optimism, but the kind which is meaningful, one that is rather close to that notion of the world which is not perfect, but which can be improved. In other words, we don't just sit and hope that things will work out; we have a role to play to make that come about. That seems to me to be the reason for the existence of the writer.

Achebe builds on this thought in his response to Wachtel's inquiry about how he convinces people of "the redemptive power of fiction":

Good stories attract us and good stories are also moral stories. I've never seen a really good story that is immoral, and I think there is something in us which impels us towards good stories. If we have people who produce them, we are lucky…

Good stories attract us and good stories are also moral stories. I've never seen a really good story that is immoral, and I think there is something in us which impels us towards good stories. If we have people who produce them, we are lucky…

I feel that there has to be a purpose to what we do. If there was no hope at all, we should just sleep or drink and wait for death. But we don't want to do that. And why? I think something tells us that we should struggle. We don't really know why we should struggle, but we do, because we think it's better than sitting down and waiting for calamity. So that's my sense of the meaning of life. That's really how I would put it, that we struggle, and because we struggle, that struggle has to be told, the story of that struggle has to be conveyed to another generation. You have struggle and story, and these two are quite enough for me.

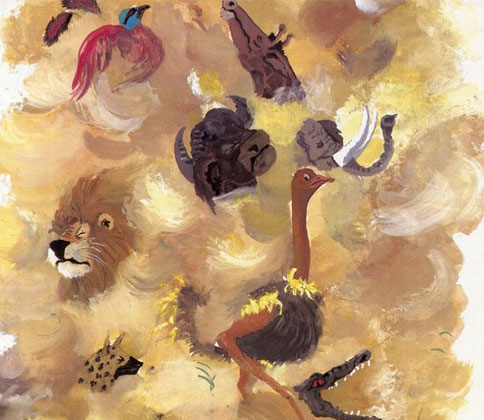

Illustration from Beneath the Rainbow, a collection of mystical children's stories featuring motifs and characters from traditional African myths reimagined by contemporary writers and artists

One of Achebe's novels, Anthills of the Savannah, features a poignant fable that illustrates his point about the meaningfulness of the struggle itself, which he relays to Wachtel:

The leopard had been looking for the tortoise and hadn't found him for a long time. On this day, on a lonely road, he suddenly chanced upon Tortoise, and so he said, "Aha! At last, I've caught you. Now get ready to die." Tortoise of course knew that the game was up and so he said, "Okay, but can I ask you a favor?" and Leopard said, "Well, why not?" Tortoise said, "Before you kill me, could you give me a few moments just to reflect on things?" Leopard thought about it – he wasn't very bright – and he said, "Well, I don't see anything wrong with that. You can have a little time." And so Tortoise, instead of standing still and thinking, began to do something very strange: he began to scratch the soil all around him and throw sand around in all directions. Leopard was mystified by this. He said, "What are you doing? Why are you doing that?" Tortoise said: "I'm doing this because when I'm dead, I want anybody who passes by this place to stop and say, 'Two people struggled here. A man met his match here.

The leopard had been looking for the tortoise and hadn't found him for a long time. On this day, on a lonely road, he suddenly chanced upon Tortoise, and so he said, "Aha! At last, I've caught you. Now get ready to die." Tortoise of course knew that the game was up and so he said, "Okay, but can I ask you a favor?" and Leopard said, "Well, why not?" Tortoise said, "Before you kill me, could you give me a few moments just to reflect on things?" Leopard thought about it – he wasn't very bright – and he said, "Well, I don't see anything wrong with that. You can have a little time." And so Tortoise, instead of standing still and thinking, began to do something very strange: he began to scratch the soil all around him and throw sand around in all directions. Leopard was mystified by this. He said, "What are you doing? Why are you doing that?" Tortoise said: "I'm doing this because when I'm dead, I want anybody who passes by this place to stop and say, 'Two people struggled here. A man met his match here.

Wachtel's More Writers & Company, a sequel to her first compendium of interviews, is a treasure trove of wisdom from cover to cover, featuring remarkably wide-ranging and dimensional conversations with such literary icons as Harold Bloom, Oliver Sacks, Isabel Allende, Alice Walker, and John Berger.

For more meditations on the meaning of life, see these timeless reflections by Maya Angelou, David Foster Wallace, Milton Glaser, Viktor Frankl, Leo Tolstoy, Carl Sagan, Anaïs Nin, Richard Feynman, Henry Miller and John Steinbeck.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

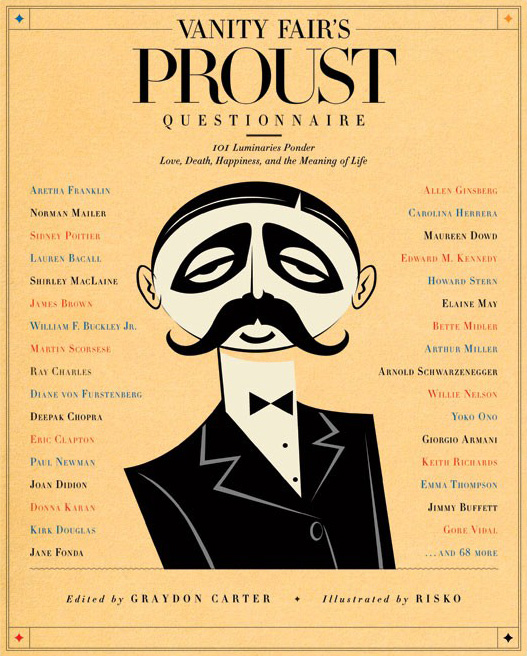

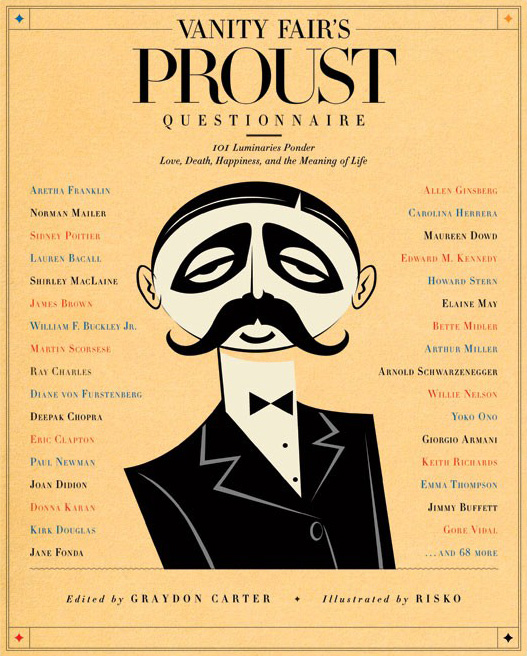

In the 1880s, long before he claimed his status as one of the greatest authors of all time, teenage Marcel Proust (July 10, 1871–November 18, 1922) filled out an English-language questionnaire given to him by his friend Antoinette, the daughter of France's then-president, as part of her "confession album" – a Victorian version of today's popular personality tests, designed to reveal the answerer's tastes, aspirations, and sensibility in a series of simple questions. Proust's original manuscript, titled "by Marcel Proust himself," wasn't discovered until 1924, two years after his death. Decades later, the French television host Bernard Pivot, whose work inspired James Lipton's Inside the Actor's Studio, saw in the questionnaire an excellent lubricant for his interviews and began administering it to his guests in the 1970s and 1980s. In 1993, Vanity Fair resurrected the tradition and started publishing various public figures' answers to the Proust Questionnaire on the last page of each issue.

In the 1880s, long before he claimed his status as one of the greatest authors of all time, teenage Marcel Proust (July 10, 1871–November 18, 1922) filled out an English-language questionnaire given to him by his friend Antoinette, the daughter of France's then-president, as part of her "confession album" – a Victorian version of today's popular personality tests, designed to reveal the answerer's tastes, aspirations, and sensibility in a series of simple questions. Proust's original manuscript, titled "by Marcel Proust himself," wasn't discovered until 1924, two years after his death. Decades later, the French television host Bernard Pivot, whose work inspired James Lipton's Inside the Actor's Studio, saw in the questionnaire an excellent lubricant for his interviews and began administering it to his guests in the 1970s and 1980s. In 1993, Vanity Fair resurrected the tradition and started publishing various public figures' answers to the Proust Questionnaire on the last page of each issue.

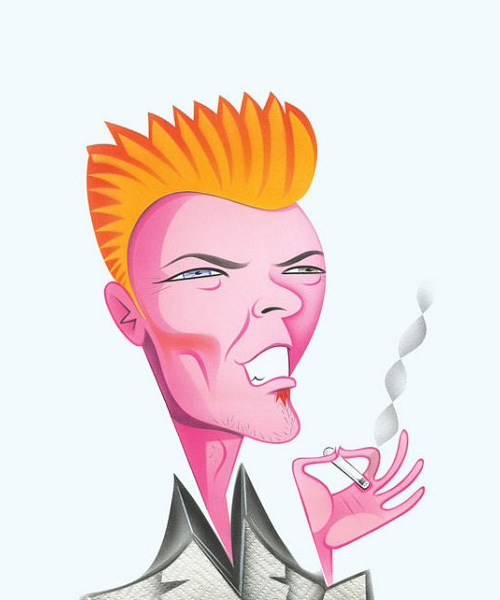

In 2009, the magazine released Vanity Fair's Proust Questionnaire: 101 Luminaries Ponder Love, Death, Happiness, and the Meaning of Life (public library) – a charming compendium featuring answers by such cultural icons as Jane Goodall, Allen Ginsberg, Hedy Lamarr, Gore Vidal, Julia Child, and Joan Didion. Among the most wonderful answers, equal parts playful and profound, are those by David Bowie – himself a vocal lover of literature – published in the magazine in August of 1998.

Portrait of David Bowie by Robert Risko

What is your idea of perfect happiness? Reading.

What is your idea of perfect happiness? Reading.

What is your most marked characteristic?

Getting a word in edgewise.

What do you consider your greatest achievement?

Discovering morning.

What is your greatest fear?

Converting kilometers to miles.

What historical figure do you most identify with?

Santa Claus.

Which living person do you most admire?

Elvis.

Who are your heroes in real life?

The consumer.

What is the trait you most deplore in yourself?

While in New York, tolerance. Outside New York, intolerance.

What is the trait you most deplore in others?

Talent.

What is your favorite journey?

The road of artistic excess.

What do you consider the most overrated virtue?

Sympathy and originality.

Which word or phrases do you most overuse?

"Chthonic," "miasma."

What is your greatest regret?

That I never wore bellbottoms.

What is your current state of mind?

Pregnant.

If you could change one thing about your family, what would it be?

My fear of them (wife and son excluded).

What is your most treasured possession?

A photograph held together by cellophane tape of Little Richard that I bought in 1958, and a pressed and dried chrysanthemum picked on my honeymoon in Kyoto.

What do you regard as the lowest depth of misery?

Living in fear.

Where would you like to live?

Northeast Bali or south Java.

What is your favorite occupation?

Squishing paint on a senseless canvas.

What is the quality you most like in a man?

The ability to return books.

What is the quality you most like in a woman?

The ability to burp on command.

What are your favorite names?

Sears & Roebuck.

What is your motto?

"What" is my motto.

Vanity Fair's Proust Questionnaire is a treat in its colorful totality. For a similar compendium of wisdom from cultural icons, see LIFE Magazine's 1991 volume The Meaning of Life, then revisit Bowie's 75 must-read books.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

If you enjoyed this week's newsletter, please consider helping with a small donation.

Hey bob sefcik! If you missed last week's edition – Paul Graham on how to make wealth, the science of our mental time travel and how it makes us human, Maya Angelou's beautiful letter to her younger self, how to get out of your own way and unblock the "spiritual electricity" of creative flow, and more – you can catch up

Hey bob sefcik! If you missed last week's edition – Paul Graham on how to make wealth, the science of our mental time travel and how it makes us human, Maya Angelou's beautiful letter to her younger self, how to get out of your own way and unblock the "spiritual electricity" of creative flow, and more – you can catch up