Hey bob sefcik! If you missed last week's edition – Leonard Cohen and the art of stillness, Anne Lamott on friendship and what it really means to let yourself be seen, my conversation with Amanda Palmer on the art of asking, Maira Kalman's design-history alphabet book, and more – you can catch up right here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation – every little bit helps, and comes enormously appreciated.

Hey bob sefcik! If you missed last week's edition – Leonard Cohen and the art of stillness, Anne Lamott on friendship and what it really means to let yourself be seen, my conversation with Amanda Palmer on the art of asking, Maira Kalman's design-history alphabet book, and more – you can catch up right here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation – every little bit helps, and comes enormously appreciated.

"I don't write for children," Maurice Sendak scoffed in his final interview. "I write – and somebody says, 'That's for children!'"

"I don't write for children," Maurice Sendak scoffed in his final interview. "I write – and somebody says, 'That's for children!'"

"It is an error," wrote J.R.R. Tolkien seven decades earlier in his superb meditation on fantasy and why there's no such thing as writing for children, "to think of children as a special kind of creature, almost a different race, rather than as normal, if immature, members of a particular family, and of the human family at large." Indeed, books that bewitch young hearts and tickle young minds aren't "children's books" but simply great books – hearts that beat in the chest of another, even if that chest is slightly smaller.

This is certainly the case with the most intelligent and imaginative "children's" and picture-books published this year. (Because the best children's books provide, as Tolkien believed, perennial delight, step into the time machine and revisit previous selections for 2013, 2012, 2011, and 2010.)

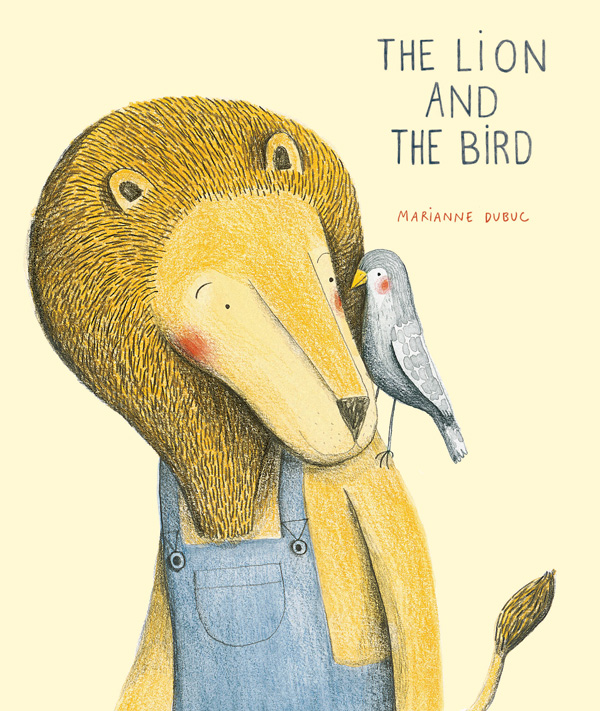

1. THE LION AND THE BIRD

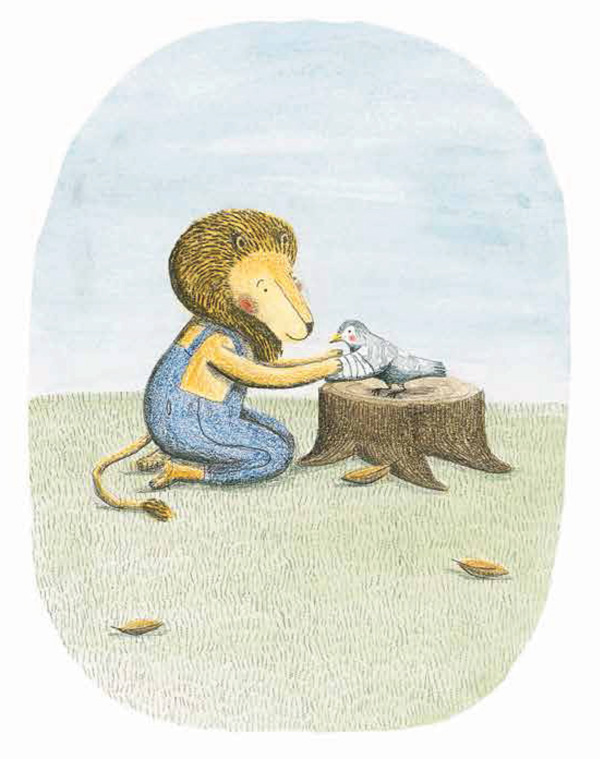

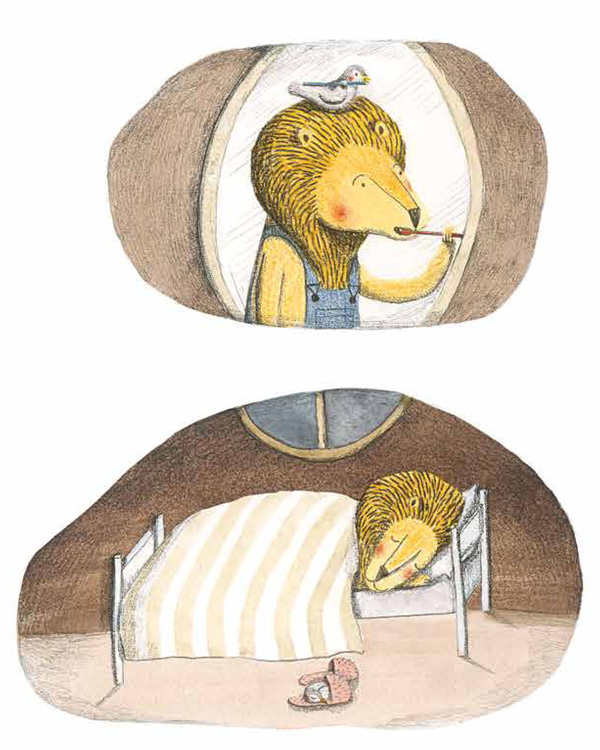

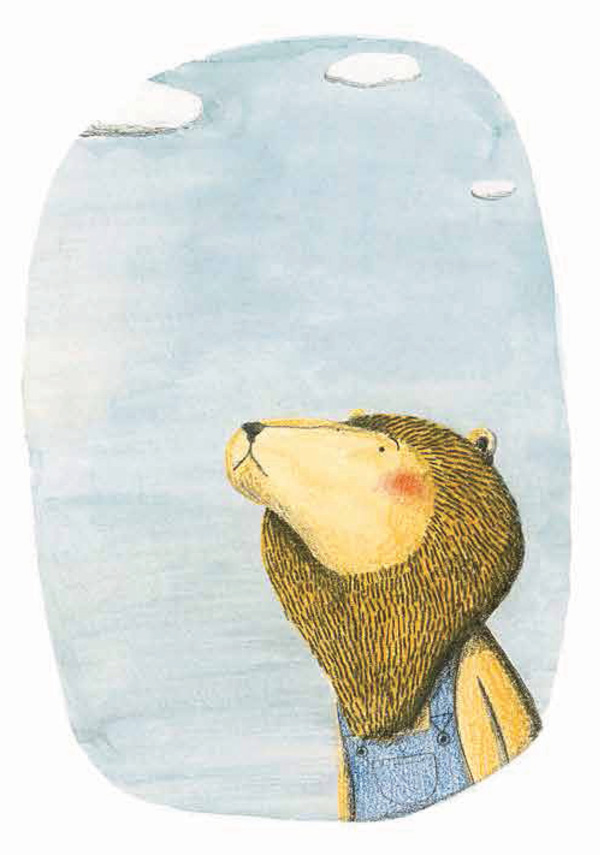

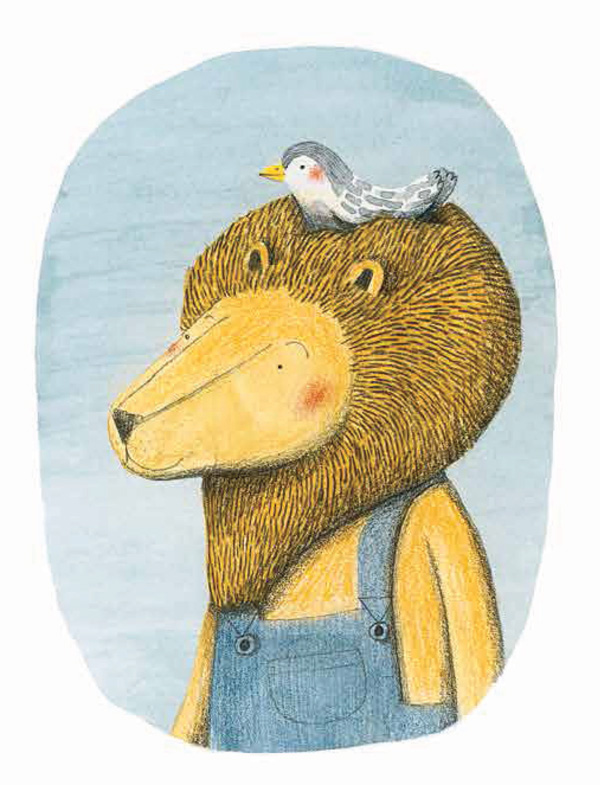

Once in a long while, a children's book comes by that is so gorgeous in sight and spirit, so timelessly and agelessly enchanting, that it takes my breath away. The Lion and the Bird (public library | IndieBound) by French Canadian graphic designer and illustrator Marianne Dubuc is one such rare gem – an ode to life's moments between the words via the tender and melodic story of a lion who finds a wounded bird in his garden one autumn day and nurses it back to flight. In the act of helping and being helped, the two deliver one another from the soul-wrenching pain of loneliness and build a beautiful friendship – the quiet and deeply rewarding kind.

Once in a long while, a children's book comes by that is so gorgeous in sight and spirit, so timelessly and agelessly enchanting, that it takes my breath away. The Lion and the Bird (public library | IndieBound) by French Canadian graphic designer and illustrator Marianne Dubuc is one such rare gem – an ode to life's moments between the words via the tender and melodic story of a lion who finds a wounded bird in his garden one autumn day and nurses it back to flight. In the act of helping and being helped, the two deliver one another from the soul-wrenching pain of loneliness and build a beautiful friendship – the quiet and deeply rewarding kind.

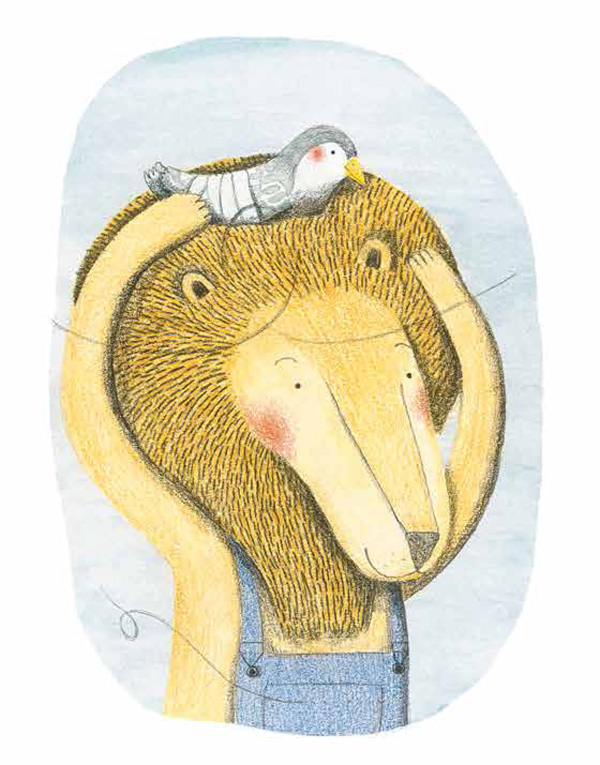

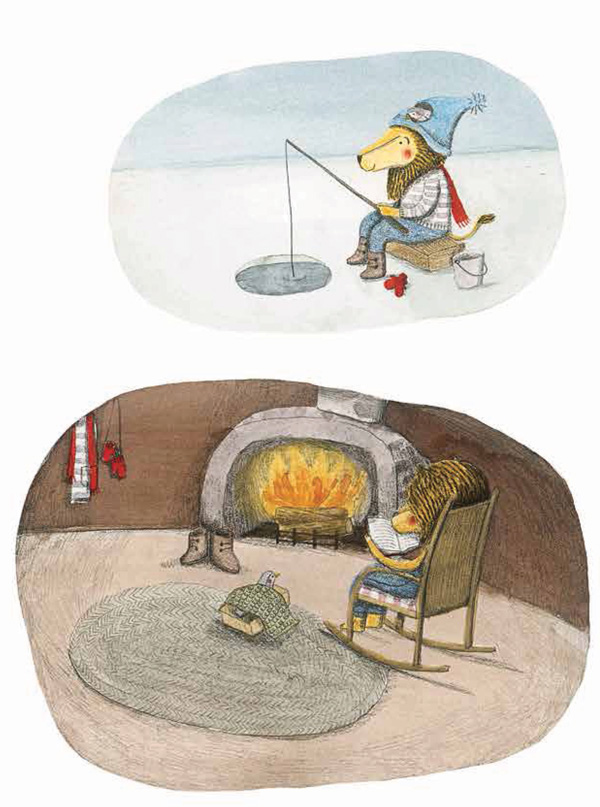

Dubuc's warm and generous illustrations are not only magical in that singular way that only someone who understands both childhood and loneliness can afford, but also lend a mesmerizing musical quality to the story. She plays with scale and negative space in a courageous and uncommon way – scenes fade into opacity as time passes, Lion shrinks as Bird flies away, and three blank pages punctuate the story as brilliantly placed pauses that capture the wistfulness of waiting and longing. What emerges is an entrancing sing-song rhythm of storytelling and of emotion.

As an endless winter descends upon Lion and Bird, they share a world of warmth and playful fellowship.

But a bittersweet awareness lurks in the shadow of their union – Lion knows that as soon as her broken wing heals, Bird will take to the spring skies with her flock, leaving him to his lonesome life.

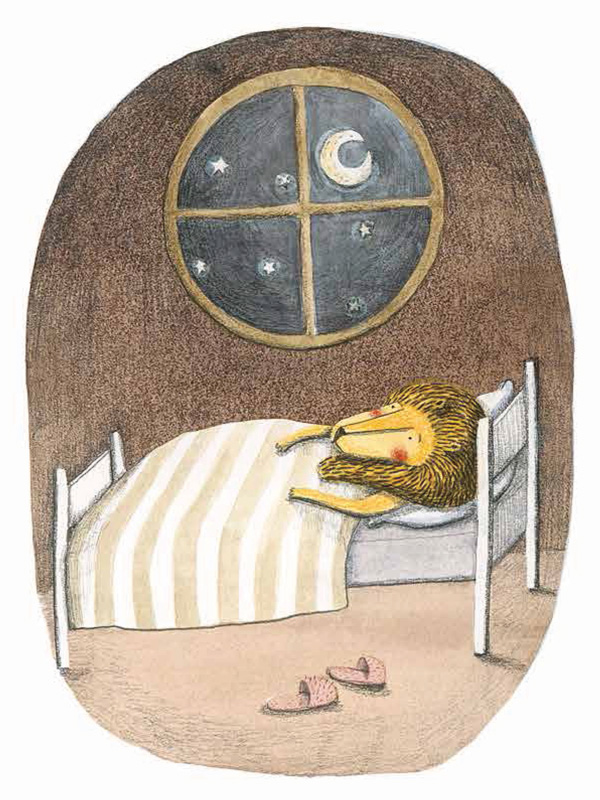

Dubuc's eloquent pictures advance the nearly wordless story, true to those moments in life that render words unnecessary. When spring arrives, we see Bird wave farewell to Lion.

"Yes," says Lion. "I know."

"Yes," says Lion. "I know."

Nothing else is said, and yet we too instantly know – we know the universe of unspoken and ineffable emotion that envelops each and beams between them like silent starlight in that fateful moment.

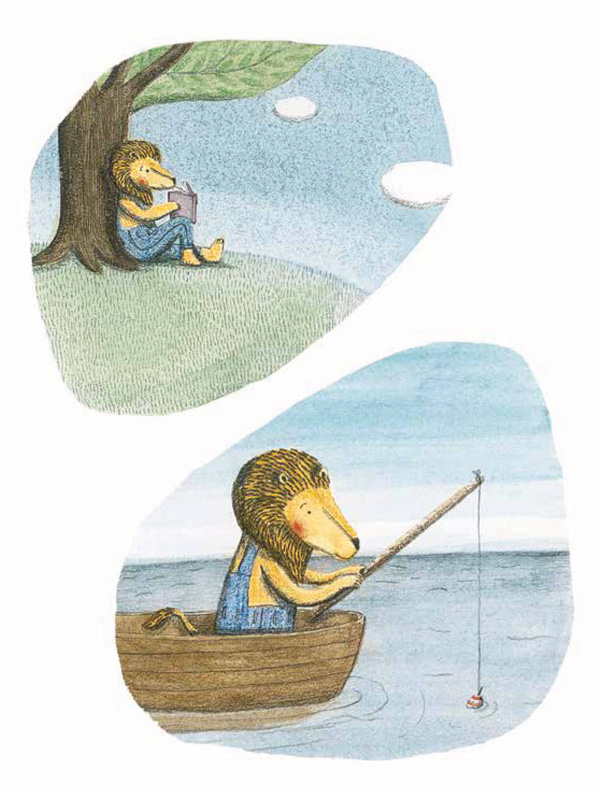

The seasons roll by and Lion tends to his garden quietly, solemnly.

Summer passes slowly, softly.

Summer passes slowly, softly.

Wistfully, he wonders where Bird might be. Until one autumn day…

…he hears a familiar sound.

It is Bird, returning for another winter of warmth and friendship.

The Lion and the Bird is ineffably wonderful, the kind of treasure to which the screen and the attempted explanation do no justice – a book that, as it was once said of The Little Prince, will shine upon your soul, whether child or grown-up, "with a sidewise gleam" and strike you "in some place that is not the mind" to glowing there with inextinguishable light.

Originally featured here.

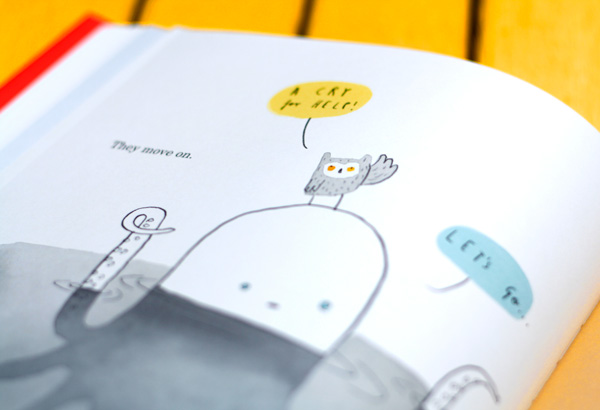

2. HUG ME

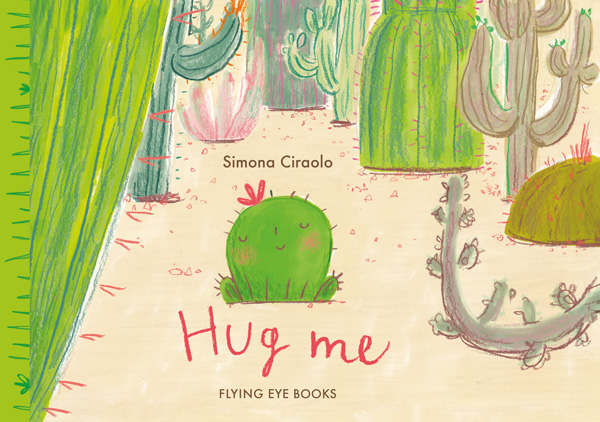

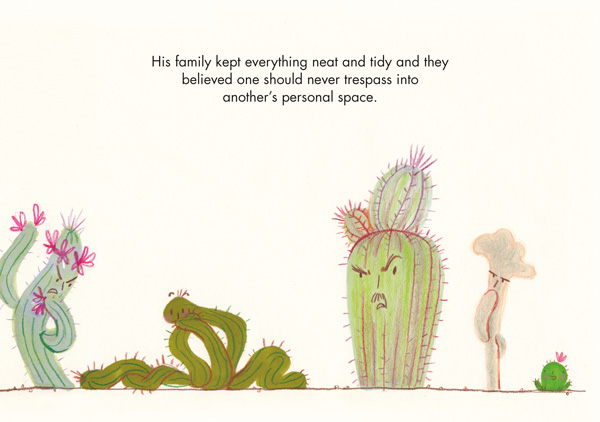

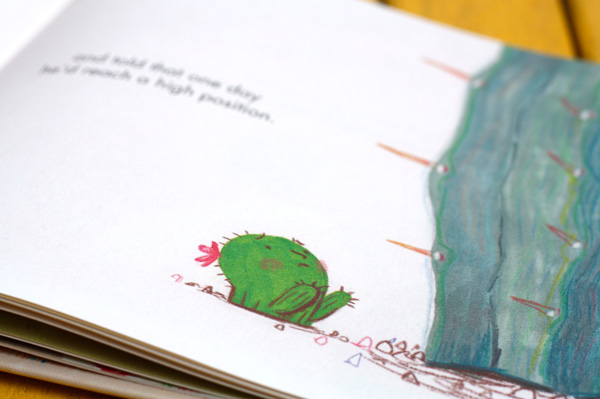

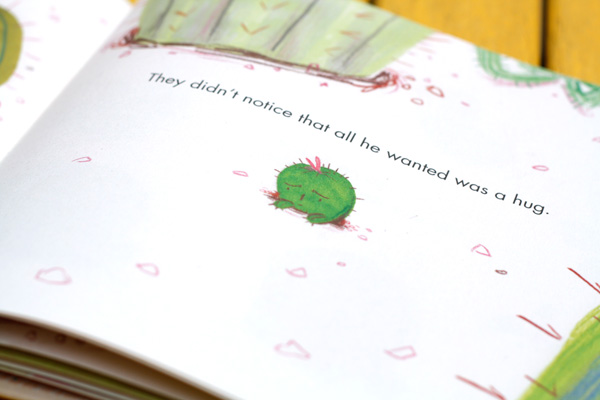

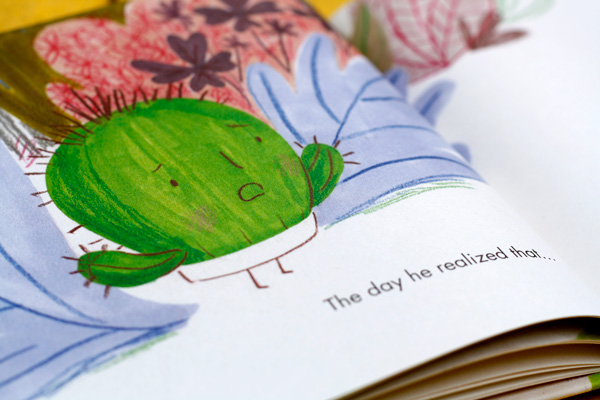

A hug is such a simple act. But how anguishing when one is denied this basic exchange of human goodwill and kindness. Surely, one doesn't even have to be human to feel the anguish of that denial. At first glance, this seems to be the premise behind Hug Me (public library | IndieBound) by animator-turned-children's-book-author Simona Ciraolo – a sweet story about a young cactus named Felipe, who longs for such softness of contact in a family that sees emotional expression as a sign of weakness. Felipe runs away, looking for a new family to give him the affection he yearns for, but only finds heartbreak and rejection.

A hug is such a simple act. But how anguishing when one is denied this basic exchange of human goodwill and kindness. Surely, one doesn't even have to be human to feel the anguish of that denial. At first glance, this seems to be the premise behind Hug Me (public library | IndieBound) by animator-turned-children's-book-author Simona Ciraolo – a sweet story about a young cactus named Felipe, who longs for such softness of contact in a family that sees emotional expression as a sign of weakness. Felipe runs away, looking for a new family to give him the affection he yearns for, but only finds heartbreak and rejection.

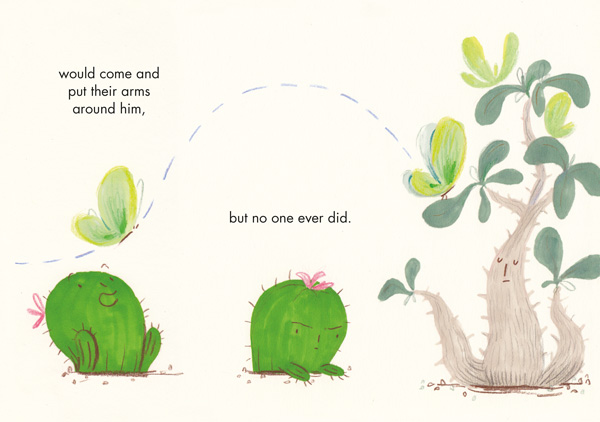

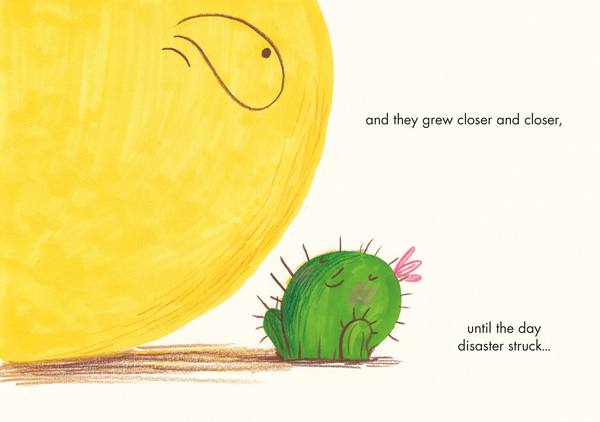

Felipe's lonesomeness grows deeper when his first friend, a "bold, confident" giant yellow balloon who hovers over Felipe's solitary patch of desert, succumbs to the inevitable outcome of the mismatched relationship. Even as he grieves his friend, Felipe is scolded for his emotional sensitivity rather than comforted with the very hug he needs.

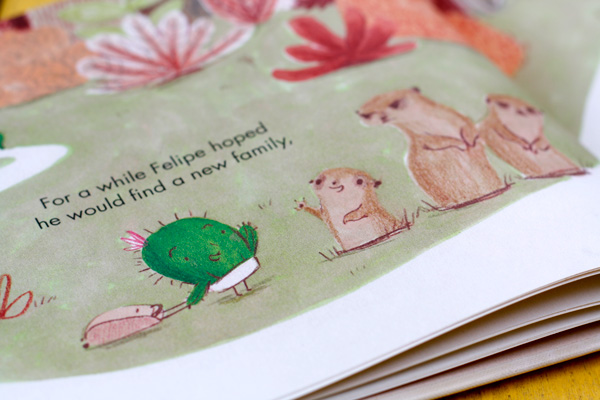

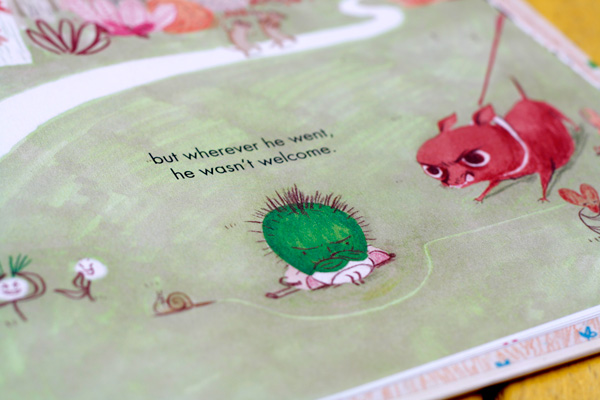

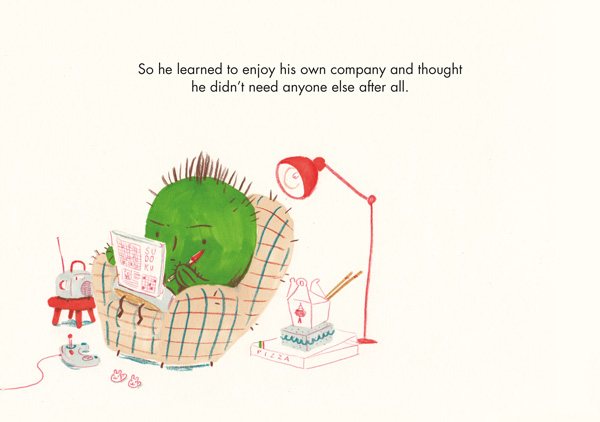

Reaching his emotional tipping point, he finally departs to look for a new family, but quickly realizes that he is unwelcome everywhere and is left with nothing but his own company – not the self-elected art of solitude that can be so nourishing, but a forced lonesomeness that saddens the soul.

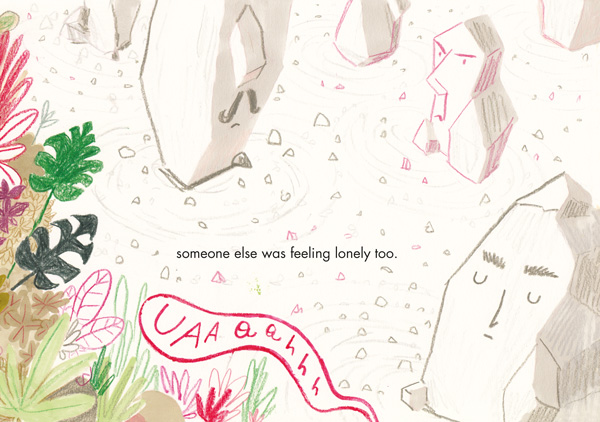

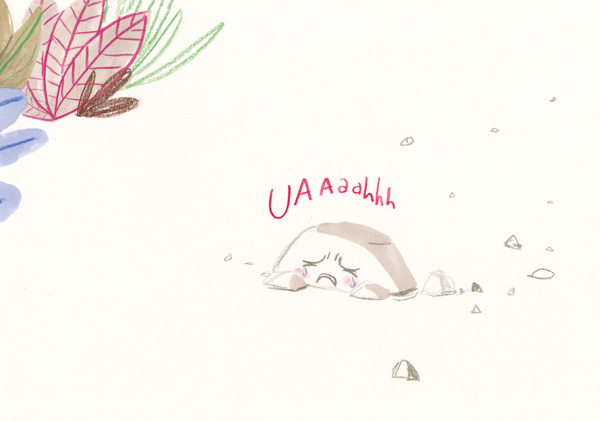

At last, Felipe finds a true friend in a little rock longing for affection amid a family as stiff and stern as his own, a kindred spirit whose cries for connection resonate in perfect unison with his own – a sweet finale reminding us that nothing dissolves loneliness like empathy and the awareness of shared experience.

There is, of course, a deeper allegorical undertone to the tale, beyond the surface interpretation of celebrating one's inner softness in a culture that encourages hard individualism and a prickly exterior. A subtle undercurrent celebrates the spiritual homecoming of finding one's tribe, the expansive embrace found in a kinship of souls. The story is also a celebration of free will, reminding us ever so gently that whatever our circumstances, we always have choices – and that our inability to see this is perhaps our gravest self-imposed limitation.

Originally featured here.

[ SEE NUMBERS 3-4 ]

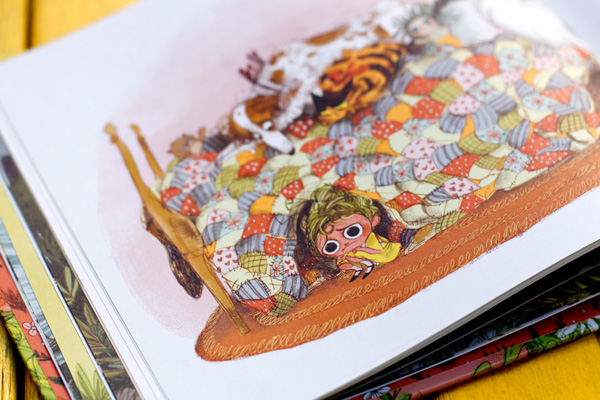

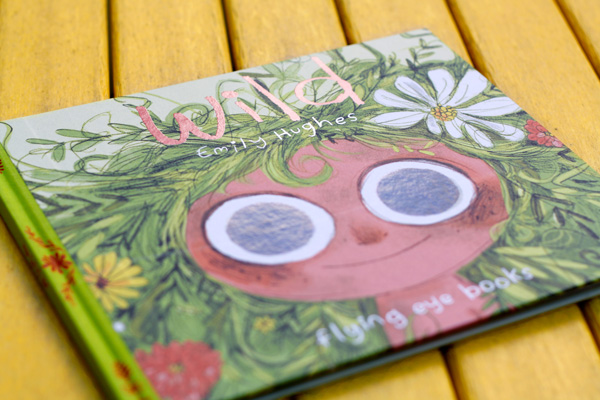

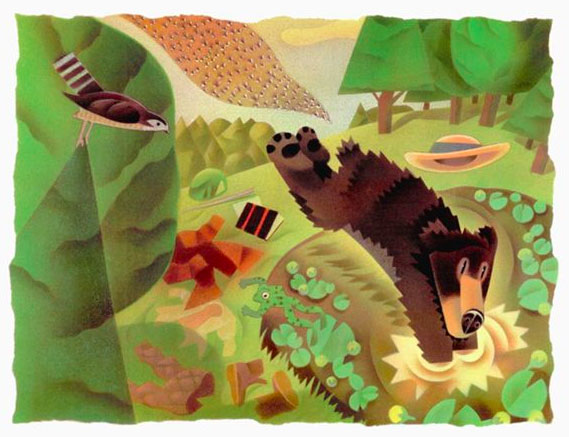

5. WILD

"All good things are wild and free," Thoreau wrote in his terrific treatise on walking. More than 150 years later, Hawaiian-born, British-based illustrator Emily Hughes makes an imaginative 21st-century case for this in Wild (public library | IndieBound) – an irreverent, charming, and oh-so-delightfully illustrated story, partway between Kipling's The Jungle Book and Sendak's Where the Wild Things Are, and one of the most endearing things to come by in decades.

"All good things are wild and free," Thoreau wrote in his terrific treatise on walking. More than 150 years later, Hawaiian-born, British-based illustrator Emily Hughes makes an imaginative 21st-century case for this in Wild (public library | IndieBound) – an irreverent, charming, and oh-so-delightfully illustrated story, partway between Kipling's The Jungle Book and Sendak's Where the Wild Things Are, and one of the most endearing things to come by in decades.

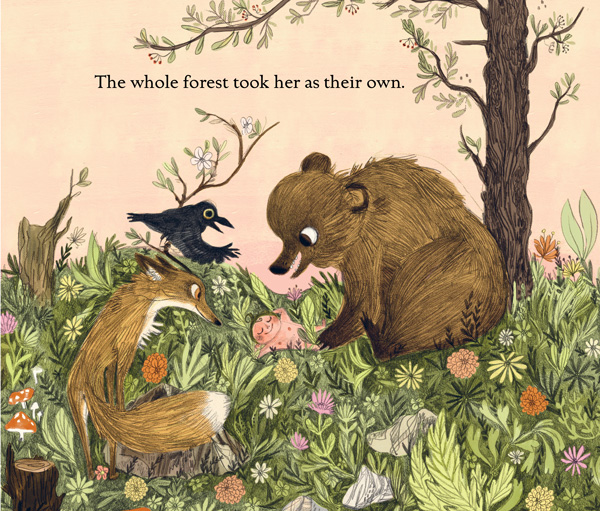

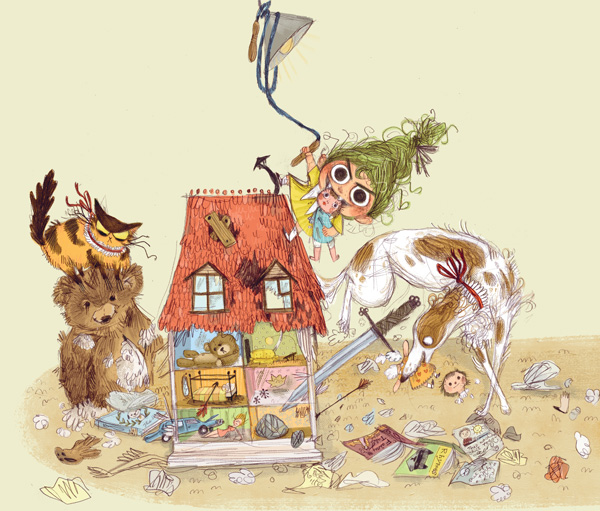

The story opens with a joyful and carefree little girl native to the woods, raised by the creatures of the whole forest. She is boundlessly, ebulliently wild, and wholly unashamed of her wildness.

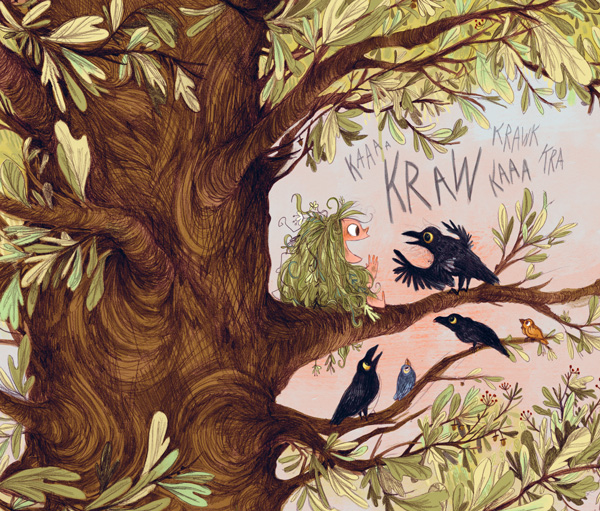

Bird taught her to speak.

Bird taught her to speak.

Bear taught her how to eat.

Fox taught her how to play.

And she understood, and was happy.

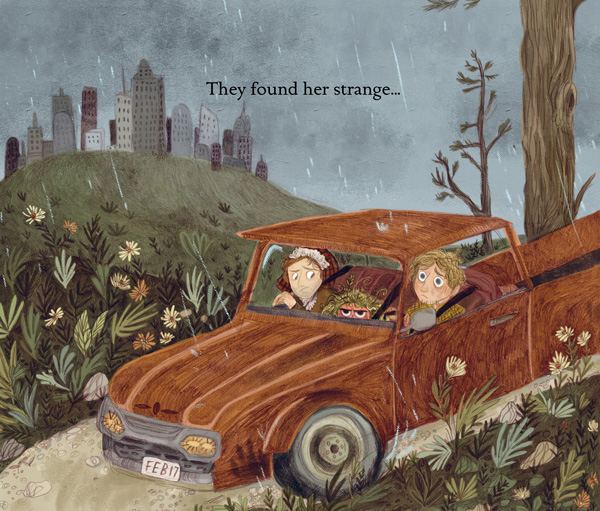

One day, two creatures who look an awful lot like her, only bigger, appear out of nowhere, put her in the belly of their metal beast, and hurl her into a wholly different new life – a civilized one.

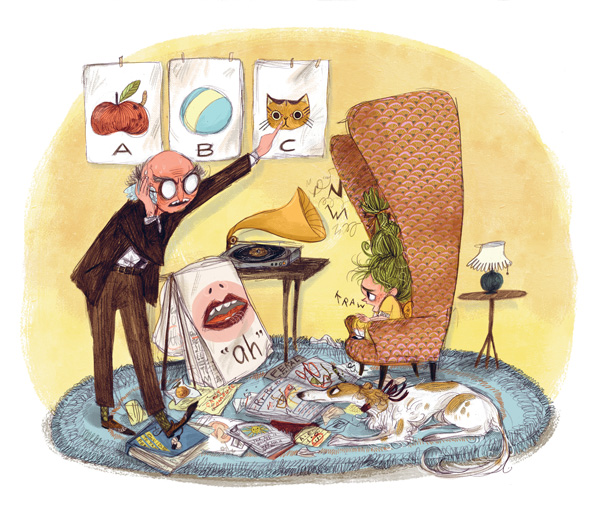

Off in the big city, a somewhat well-meaning but rather dictatorial elderly couple sets out to de-wild her. "FAMED PSYCHIATRIST TAKES IN FERAL CHILD," a newspaper headline proclaims.

The little girl is frightened, but mostly perplexed.

They spoke wrong.

They spoke wrong.

They ate wrong.

They played wrong.

And she did not understand, and she was not happy.

One day, she has had enough.

Because you cannot tame something so happily wild...

Because you cannot tame something so happily wild...

Emanating from the playful and poetic story is a clarion call to shake off the external should's that shackle us and stop keeping ourselves small by trying to please others, to celebrate what John Steinbeck called "the freedom of the mind to take any direction it wishes, undirected". It is an invitation, at once tender and mischievous, to pause and ask, as Mary Oliver memorably did: "What is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?"

Originally featured here.

[ SEE NUMBERS 6-7 ]

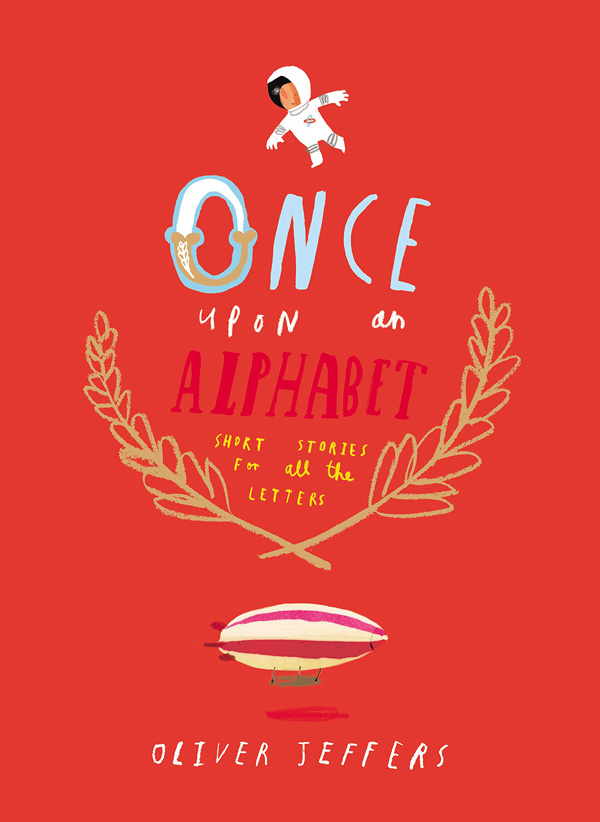

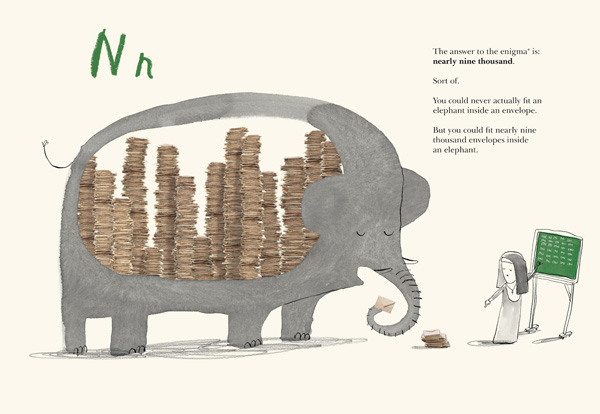

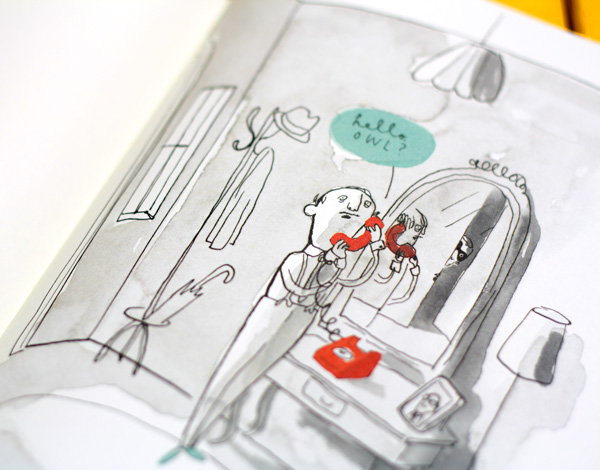

8. ONCE UPON AN ALPHABET

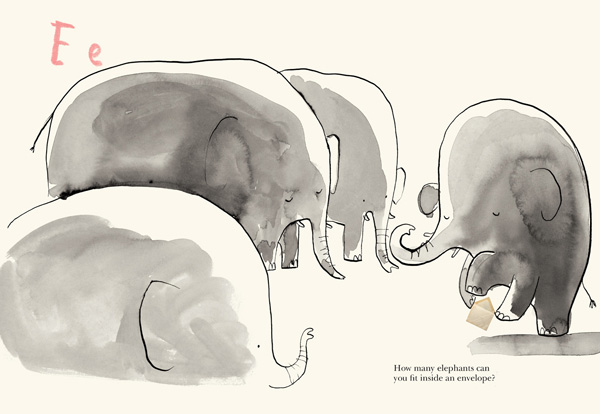

In the 1990s, three decades after the debut of his now-iconic grim alphabet book, the great Edward Gorey reimagined the letters in a series of 26-word cryptic stories. Now comes a worthy modern counterpart by one of the most original and imaginative children's book storytellers and artists of our time: Once Upon an Alphabet: Short Stories for All the Letters (public library | IndieBound) by Oliver Jeffers – an unusual and utterly wonderful tour of the familiar letters that takes a whimsical detour via quirky, lyrical, delightfully alliterative tales for each, and makes a fine addition to the canon of offbeat alphabet books.

In the 1990s, three decades after the debut of his now-iconic grim alphabet book, the great Edward Gorey reimagined the letters in a series of 26-word cryptic stories. Now comes a worthy modern counterpart by one of the most original and imaginative children's book storytellers and artists of our time: Once Upon an Alphabet: Short Stories for All the Letters (public library | IndieBound) by Oliver Jeffers – an unusual and utterly wonderful tour of the familiar letters that takes a whimsical detour via quirky, lyrical, delightfully alliterative tales for each, and makes a fine addition to the canon of offbeat alphabet books.

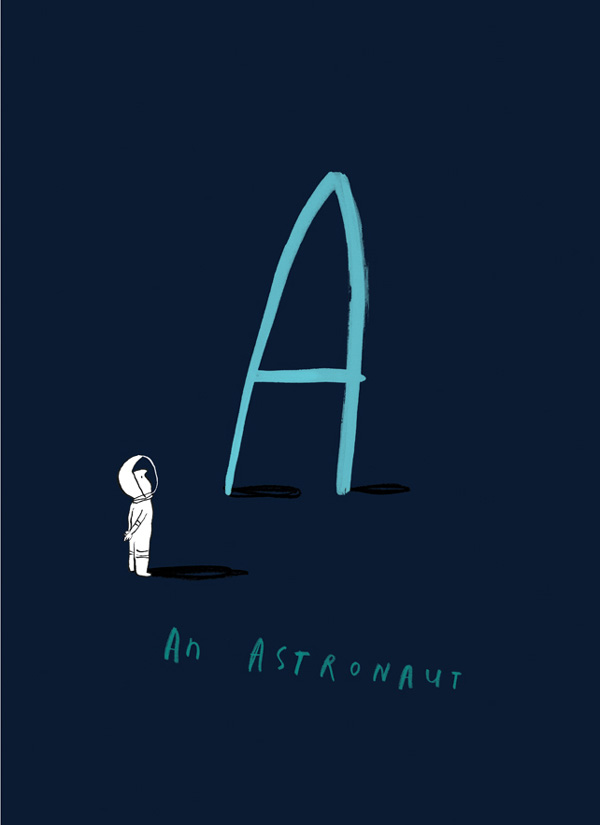

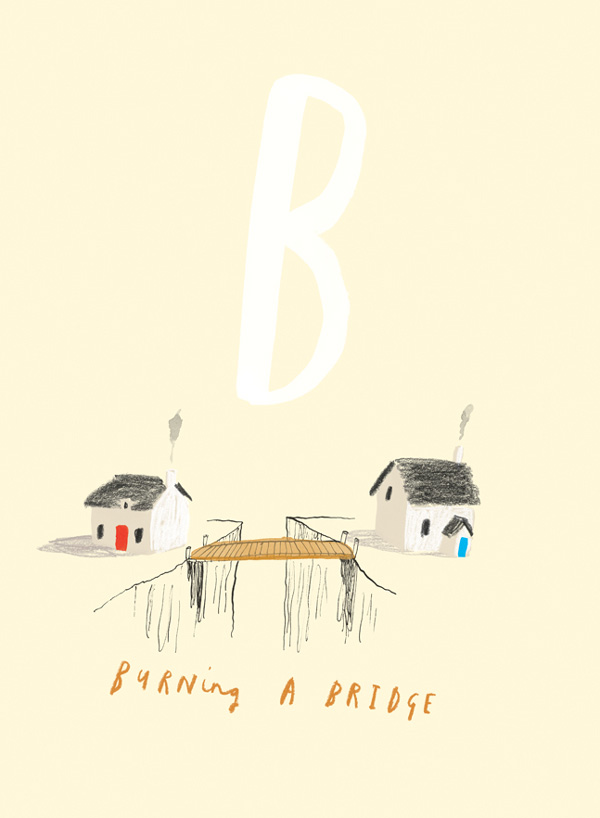

Jeffers's art is subtle yet immeasurably expressive. His stories brim with the fallible and heartening humanity that makes up our vastly imperfect but mostly noble selves – our paradoxes (A is for "astronaut," and Edmund the astronaut is afraid of heights), the silly stubbornnesses (B is for "burning a bridge" and we meet neighbors Bernard and Bob, who have spent years "battling each other for reasons neither could remember"), the playful flights of curiosity (E is for "enigma," like the question of how many elephants can fit inside an envelope), the existential perplexities (in P, a "puzzled parsnip" spirals into anguish over realizing that he is neither a carrot nor a potato), the self-defeating control tactics we employ in attempting to assuage our fear of impermanence (the robots in R are so terrified of rusting that they steal the rainclouds from the sky and lug them around in carts).

There are touches of loveliness and thoughtfulness: The budding scientist (M is for "made of matter") is a little girl and the manly lumberjack (L) lucubrates by lamplight, reading a copy of Once Upon an Alphabet.

There are also charming winks at continuity: The nun in N flips the enigma from E and posits that "nearly nine thousand" envelopes can fit inside an elephant; the fearless owl and octopus duo in O, who roam the ocean searching for problems to solve, come to the rescue when a regular cucumber plunges into the ocean in S (for "sink or swim") because he "watched a program about sea cucumbers and thought it might be a better life for him," only to realize he didn't know how to swim; when Xavier in X wakes up one morning and is devastated to find out that his prized X-ray spectacles have been stolen, he rings the owl and the octopus for help.

There is, too, a sprinkle of Goreyesque darkness alongside the delight, speaking to Maurice Sendak's conviction that children shouldn't be sheltered from the dark: In T, a writer sits in front of his "terrible typewriter," which has the uncanny ability to make his stories come true, until one day he is eaten by a monster he wrote. (The creature, coincidentally, is reminiscent of Sendak's Wild Things.) In H, Helen lives in a half house, the other half having been swept into...

:: SEE FULL LIST 1-15 / SHARE ::

Since long before the question of where good ideas come from became the psychologists' favorite sport, readers, fans, and audiences have been hurling it at authors and artists, much to their frustration. A few brave souls like Neil Gaiman, Albert Einstein, and David Lynch have attempted to answer it directly, or in Leonard Cohen's case to delightfully non-answer it directly, but none have done so with greater vigor of mind and heart than Ursula K. Le Guin – a writer of extraordinary wisdom delivered with irresistible wit, and the eloquent recipient of the National Book Foundation's 2014 Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters.

Since long before the question of where good ideas come from became the psychologists' favorite sport, readers, fans, and audiences have been hurling it at authors and artists, much to their frustration. A few brave souls like Neil Gaiman, Albert Einstein, and David Lynch have attempted to answer it directly, or in Leonard Cohen's case to delightfully non-answer it directly, but none have done so with greater vigor of mind and heart than Ursula K. Le Guin – a writer of extraordinary wisdom delivered with irresistible wit, and the eloquent recipient of the National Book Foundation's 2014 Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters.

In 1987, Le Guin addressed the eternal question in an essay titled "Where Do You Get Your Ideas From?," found in the altogether fantastic 1989 collection of her speeches, essays, and reviews, Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places (public library | IndieBound).

Noting that audiences frequently ask her the canonical question after lectures and talks, she considers the two reasons that make it impossible to answer:

The reason why it is unanswerable is, I think, that it involves at least two false notions, myths, about how fiction is written.

The reason why it is unanswerable is, I think, that it involves at least two false notions, myths, about how fiction is written.

First myth: There is a secret to being a writer. If you can just learn the secret, you will instantly be a writer; and the secret might be where the ideas come from.

Second myth: Stories start from ideas; the origin of a story is an idea.

Well before psychologists' pioneering findings to that effect, Le Guin writes:

I will dispose of the first myth as quickly as possible. The "secret" is skill. If you haven't learned how to do something, the people who have may seem to be magicians, possessors of mysterious secrets. In a fairly simple art, such as making pie crust, there are certain teachable "secrets" of method that lead almost infallibly to good results; but in any complex art, such as housekeeping, piano-playing, clothes-making, or story-writing, there are so many techniques, skills, choices of method, so many variables, so many "secrets," some teachable and some not, that you can learn them only by methodical, repeated, long-continued practice – in other words, by work.

I will dispose of the first myth as quickly as possible. The "secret" is skill. If you haven't learned how to do something, the people who have may seem to be magicians, possessors of mysterious secrets. In a fairly simple art, such as making pie crust, there are certain teachable "secrets" of method that lead almost infallibly to good results; but in any complex art, such as housekeeping, piano-playing, clothes-making, or story-writing, there are so many techniques, skills, choices of method, so many variables, so many "secrets," some teachable and some not, that you can learn them only by methodical, repeated, long-continued practice – in other words, by work.

[...]

Some of the secretiveness of many artists about their techniques, recipes, etc., may be taken as a warning to the unskilled: What works for me isn't going to work for you unless you've worked for it.

Seconding Jack Kerouac's question of whether writers are born or made, Le Guin considers the role of what we call natural talent and what it lies beneath it:

My talent and inclination for writing stories and keeping house were strong from the start, and my gift for and interest in music and sewing were weak; so that I doubt that I would ever have been a good seamstress or pianist, no matter how hard I worked. But nothing I know about how I learned to do the things I am good at doing leads me to believe that there are "secrets" to the piano or the sewing machine or any art I'm no good at. There is just the obstinate, continuous cultivation of a disposition, leading to skill in performance.

My talent and inclination for writing stories and keeping house were strong from the start, and my gift for and interest in music and sewing were weak; so that I doubt that I would ever have been a good seamstress or pianist, no matter how hard I worked. But nothing I know about how I learned to do the things I am good at doing leads me to believe that there are "secrets" to the piano or the sewing machine or any art I'm no good at. There is just the obstinate, continuous cultivation of a disposition, leading to skill in performance.

She then turns to the second central fallacy of the origin-of-ideas question, namely the notion of the "idea" itself:

The more I think about the word "idea," the less idea I have what it means. ... I think this is a kind of shorthand use of "idea" to stand for the complicated, obscure, un-understood process of the conception and formation of what is going to be a story when it gets written down. The process may not involve ideas in the sense of intelligible thoughts; it may well not even involve words. It may be a matter of mood, resonances, mental glimpses, voices, emotions, visions, dreams, anything. It is different in every writer, and in many of us it is different every time. It is extremely difficult to talk about, because we have very little terminology for such processes.

The more I think about the word "idea," the less idea I have what it means. ... I think this is a kind of shorthand use of "idea" to stand for the complicated, obscure, un-understood process of the conception and formation of what is going to be a story when it gets written down. The process may not involve ideas in the sense of intelligible thoughts; it may well not even involve words. It may be a matter of mood, resonances, mental glimpses, voices, emotions, visions, dreams, anything. It is different in every writer, and in many of us it is different every time. It is extremely difficult to talk about, because we have very little terminology for such processes.

Echoing Einstein's idea of "combinatory play" and artist Francis Bacon's notion that original art is the product of finely "grinding up" one's influences, Le Guin speaks to the combinatorial nature of the creative process:

I would say that as a general rule, though an external event may trigger it, this inceptive state or story-beginning phase does not come from anywhere outside the mind that can be pointed to; it arises in the mind, from psychic contents that have become unavailable to the conscious mind, inner or outer experience that has been, in Gary Snyder's lovely phrase, composted. I don't believe that a writer "gets" (takes into the head) an "idea" (some sort of mental object) "from" somewhere, and then turns it into words and writes them on paper. At least in my experience, it doesn't work that way. The stuff has to be transformed into oneself, it has to be composted, before it can grow a story.

I would say that as a general rule, though an external event may trigger it, this inceptive state or story-beginning phase does not come from anywhere outside the mind that can be pointed to; it arises in the mind, from psychic contents that have become unavailable to the conscious mind, inner or outer experience that has been, in Gary Snyder's lovely phrase, composted. I don't believe that a writer "gets" (takes into the head) an "idea" (some sort of mental object) "from" somewhere, and then turns it into words and writes them on paper. At least in my experience, it doesn't work that way. The stuff has to be transformed into oneself, it has to be composted, before it can grow a story.

Mystical as the process may be, Le Guin goes on to outline its "five principal elements," which must "work in one insoluble unitary movement" in order to produce great writing:

- The patterns of the language – the sounds of words.

- The patterns of syntax and grammar; the way the words and sentences connect themselves together; the ways their connections interconnect to form the larger units (paragraphs, sections, chapters); hence the movement of the work, its tempo, pace, gait, and shape in time.

- The patterns of the images: what the words make us or let us see with the mind's eye or sense imaginatively.

- The patterns of the ideas: what the words and the narration of events make us understand, or use our understanding upon.

- The patterns of the feelings: what the words and the narration, by using all the above means, make us experience emotionally or spiritually, in areas of our being not directly accessible to or expressible in words.

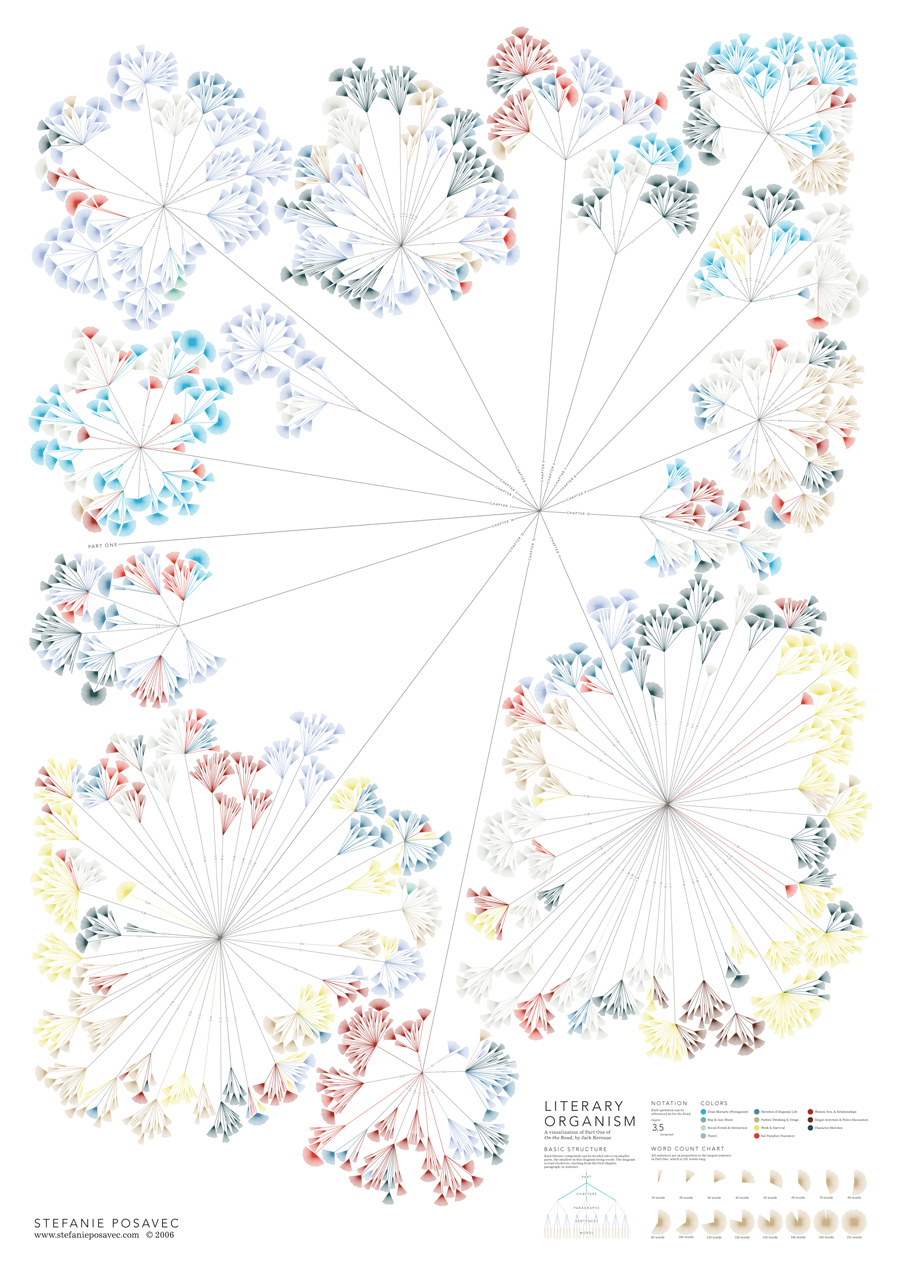

Artwork from Stefanie Posavec's Writing Without Words, visualizing the patterns of sentences, paragraphs, and words in a text.

Echoing T.S. Eliot's notion of idea incubation, she adds:

All these kinds of patterning – sound, syntax, images, ideas, feelings – have to work together; and they all have to be there in some degree. The inception of the work, that mysterious stage, is perhaps their coming together: when in the author's mind a feeling begins to connect itself to an image that will express it, and that image leads to an idea, until now half-formed, that begins to find words for itself, and the words lead to other words that make new images, perhaps of people, characters of a story, who are doing things that express the underlying feelings and ideas that are now resonating with each other.

All these kinds of patterning – sound, syntax, images, ideas, feelings – have to work together; and they all have to be there in some degree. The inception of the work, that mysterious stage, is perhaps their coming together: when in the author's mind a feeling begins to connect itself to an image that will express it, and that image leads to an idea, until now half-formed, that begins to find words for itself, and the words lead to other words that make new images, perhaps of people, characters of a story, who are doing things that express the underlying feelings and ideas that are now resonating with each other.

Considering the lopsiding of that five-point balance, Le Guin speaks to the importance of failure in growth:

If any of these processes get scanted badly or left out, in the conception stage, in the writing stage, or in the revising stage, the result will be a weak or failed story. Failure often allows us to analyze what success triumphantly hides from us.

If any of these processes get scanted badly or left out, in the conception stage, in the writing stage, or in the revising stage, the result will be a weak or failed story. Failure often allows us to analyze what success triumphantly hides from us.

In a sentiment that Rebecca Solnit would come to second decades later in reflecting on the shared intimacy of reading and writing, Le Guin deploys one of her characteristically animated metaphors that can't help but put a smile on the soul:

Beginners' failures are often the result of trying to work with strong feelings and ideas without having found the images to embody them, or without even knowing how to find the words and string them together. Ignorance of English vocabulary and grammar is a considerable liability to a writer of English. The best cure for it is, I believe, reading. People who learned to talk at two or so and have been practicing talking ever since feel with some justification that they know their language; but what they know is their spoken language, and if they read little, or read schlock, and haven't written much, their writing is going to be pretty much what their talking was when they were two.

Beginners' failures are often the result of trying to work with strong feelings and ideas without having found the images to embody them, or without even knowing how to find the words and string them together. Ignorance of English vocabulary and grammar is a considerable liability to a writer of English. The best cure for it is, I believe, reading. People who learned to talk at two or so and have been practicing talking ever since feel with some justification that they know their language; but what they know is their spoken language, and if they read little, or read schlock, and haven't written much, their writing is going to be pretty much what their talking was when they were two.

She returns to the vital balance of those five elements:

There is a relationship, a reciprocity between the words and the images, ideas, and emotions evoked by those words: the stronger that relationship, the stronger the work. To believe that you can achieve meaning or feeling without coherent, integrated patterning of the sounds, the rhythms, the sentence structures, the images, is like believing you can go for a walk without bones.

There is a relationship, a reciprocity between the words and the images, ideas, and emotions evoked by those words: the stronger that relationship, the stronger the work. To believe that you can achieve meaning or feeling without coherent, integrated patterning of the sounds, the rhythms, the sentence structures, the images, is like believing you can go for a walk without bones.

Le Guin considers the epicenter of that relationship – of the elements, of reader and writer:

Imagery takes place in "the imagination," which I take to be the meeting place of the thinking mind with the sensing body... In the imagination we can share a capacity for experience and an understanding of truth far greater than our own. The great writers share theirs souls with us – "literally."

Imagery takes place in "the imagination," which I take to be the meeting place of the thinking mind with the sensing body... In the imagination we can share a capacity for experience and an understanding of truth far greater than our own. The great writers share theirs souls with us – "literally."

[...]

The intellect cannot do the work of the imagination; the emotions cannot do the work of the imagination; and neither of them can do anything much in fiction without the imagination.

Where the writer and the reader collaborate to make the work of fiction is perhaps, above all, in the imagination. In the joint creation of the fictive world.

With a self-effacing wink at her profession and the odd creative rituals of her ilk, Le Guin considers the writer's eternal tussle with his or her consciousness of, and often self-consciousness about, the audience – an audience that, today, is exponentially more able and willing to make its presence and opinion known via likes, tweets, and other innocuously named, spiritually toxic Pavlovian mechanisms:

Writers are egotists. All artists are. They can't be altruists and get their work done. And writers love to whine about the Solitude of the Author's Life, and lock themselves into cork-lined rooms or droop around in bars in order to whine better. But although most writing is done in solitude, I believe that it is done, like all the arts, for an audience. That is to say, with an audience. All the arts are performance arts, only some of them are sneakier about it than others.

Writers are egotists. All artists are. They can't be altruists and get their work done. And writers love to whine about the Solitude of the Author's Life, and lock themselves into cork-lined rooms or droop around in bars in order to whine better. But although most writing is done in solitude, I believe that it is done, like all the arts, for an audience. That is to say, with an audience. All the arts are performance arts, only some of them are sneakier about it than others.

Illustration by Jim Stoten from Mr. Tweed's Good Deeds

But her most piercing point – one she would come to echo three decades later in her National Book Award acceptance speech – is a monumental disclaimer:

I beg you please to attend carefully now to what I am not saying. I am not saying that you should think about your audience when you write. I am not saying that the writing writer should have in mind, "Who will read this? Who will buy it? Who am I aiming this at?" – as if it were a gun. No.

I beg you please to attend carefully now to what I am not saying. I am not saying that you should think about your audience when you write. I am not saying that the writing writer should have in mind, "Who will read this? Who will buy it? Who am I aiming this at?" – as if it were a gun. No.

While planning a work, the writer may and often must think about readers: particularly if it's something like a story for children, where you need to know whether your reader is likely to be a five-year-old or a ten-year old.* Considerations of who will or might read the piece are appropriate and sometimes actively useful in planning it, thinking about it, thinking it out, inviting images. But once you start writing, it is fatal to think about anything but the writing. True work is done for the sake of doing it. What is to be done with it afterwards is another matter, another job. A story rises from the springs of creation, from the pure will to be; it tells itself; it takes its own course, finds its own way, its own words; and the writer's job is to be its medium.

And yet the reader, Le Guin argues, is an essential piece of the telling of the story. The writer's work should extend an invitation for collaboration to the reader:

The writer cannot do it alone. The unread story is not a story; it is little black marks on wood pulp. The reader, reading it, makes it alive: a live thing, a story. ... It comes down to collaboration, or sharing the gift: the writer tries to get the reader working with the text in the effort to keep the whole story all going along in one piece in the right direction (which is my general notion of a good piece of fiction).

The writer cannot do it alone. The unread story is not a story; it is little black marks on wood pulp. The reader, reading it, makes it alive: a live thing, a story. ... It comes down to collaboration, or sharing the gift: the writer tries to get the reader working with the text in the effort to keep the whole story all going along in one piece in the right direction (which is my general notion of a good piece of fiction).

In this effort, writers need all the help they can get. Even under the most skilled control, the words will never fully embody the vision. Even with the most sympathetic reader, the truth will falter and grow partial. Writers have to get used to launching something beautiful and watching it crash and burn. They also have to learn when to let go control, when the work takes off on its own and flies, farther than they ever planned or imagined, to places they didn't know they knew. All makers must leave room for the acts of the spirit. But they have to work hard and carefully, and wait patiently, to deserve them.

Dancing at the Edge of the World is a glorious read in its entirety. Complement it with Le Guin on being a man and on aging and what beauty really means.

Complement for more timeless wisdom on writing from some of history's greatest authors, see this ongoing omnibus of advice, including Elmore Leonard's ten tips on writing, Neil Gaiman's eight pointers, Nietzsche's ten rules, Walter Benjamin's thirteen doctrines, Henry Miller's eleven commandments, and Kurt Vonnegut's eight tips for writing with style, Zadie Smith on the two psychologies for writing, and Vladimir Nabokov on the three qualities of a great storyteller.

* C.S. Lewis would beg to vehemently differ, as would Tolkien, and Maurice Sendak would practically leap in protestation.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

"Go out and walk. That is the glory of life," Maira Kalman exhorted in her glorious visual memoir. A century and a half earlier, another remarkable mind made a beautiful and timeless case for that basic, infinitely rewarding, yet presently endangered human activity.

"Go out and walk. That is the glory of life," Maira Kalman exhorted in her glorious visual memoir. A century and a half earlier, another remarkable mind made a beautiful and timeless case for that basic, infinitely rewarding, yet presently endangered human activity.

Henry David Thoreau was a man of extraordinary wisdom on everything from optimism to the true meaning of "success" to the creative benefits of keeping a diary to the greatest gift of growing old. In his 1861 treatise Walking (free ebook | public library | IndieBound), penned seven years after Walden, he sets out to remind us of how that primal act of mobility connects us with our essential wildness, that spring of spiritual vitality methodically dried up by our sedentary civilization.

Illustration by D. B. Johnson from Henry Hikes to Fitchburg a children's book about Thoreau's philosophy

Intending to "regard man as an inhabitant, or a part and parcel of Nature, rather than a member of society," because "there are enough champions of civilization," Thoreau argues that the genius of walking lies not in mechanically putting one foot in front of the other en route to a destination but in mastering the art of sauntering. (In one of several wonderful asides, Thoreau offers what is perhaps the best definition of "genius": "Genius is a light which makes the darkness visible, like the lightning's flash, which perchance shatters the temple of knowledge itself – and not a taper lighted at the hearthstone of the race, which pales before the light of common day.") An avid practitioner of hiking, Thoreau extols sauntering as a different thing altogether:

I have met with but one or two persons in the course of my life who understood the art of Walking, that is, of taking walks – who had a genius, so to speak, for sauntering, which word is beautifully derived "from idle people who roved about the country, in the Middle Ages, and asked charity, under pretense of going a la Sainte Terre, to the Holy Land, till the children exclaimed, "There goes a Sainte-Terrer," a Saunterer, a Holy-Lander. They who never go to the Holy Land in their walks, as they pretend, are indeed mere idlers and vagabonds; but they who do go there are saunterers in the good sense, such as I mean. Some, however, would derive the word from sans terre, without land or a home, which, therefore, in the good sense, will mean, having no particular home, but equally at home everywhere. For this is the secret of successful sauntering. He who sits still in a house all the time may be the greatest vagrant of all; but the saunterer, in the good sense, is no more vagrant than the meandering river, which is all the while sedulously seeking the shortest course to the sea.

I have met with but one or two persons in the course of my life who understood the art of Walking, that is, of taking walks – who had a genius, so to speak, for sauntering, which word is beautifully derived "from idle people who roved about the country, in the Middle Ages, and asked charity, under pretense of going a la Sainte Terre, to the Holy Land, till the children exclaimed, "There goes a Sainte-Terrer," a Saunterer, a Holy-Lander. They who never go to the Holy Land in their walks, as they pretend, are indeed mere idlers and vagabonds; but they who do go there are saunterers in the good sense, such as I mean. Some, however, would derive the word from sans terre, without land or a home, which, therefore, in the good sense, will mean, having no particular home, but equally at home everywhere. For this is the secret of successful sauntering. He who sits still in a house all the time may be the greatest vagrant of all; but the saunterer, in the good sense, is no more vagrant than the meandering river, which is all the while sedulously seeking the shortest course to the sea.

Proclaiming that "every walk is a sort of crusade," Thoreau laments – note, a century and a half before our present sedentary society – our growing civilizational tameness, which has possessed us to cease undertaking "persevering, never-ending enterprises" so that even "our expeditions are but tours." With a dramatic flair, he lays out the spiritual conditions required of the true walker:

If you are ready to leave father and mother, and brother and sister, and wife and child and friends, and never see them again – if you have paid your debts, and made your will, and settled all your affairs, and are a free man – then you are ready for a walk.

If you are ready to leave father and mother, and brother and sister, and wife and child and friends, and never see them again – if you have paid your debts, and made your will, and settled all your affairs, and are a free man – then you are ready for a walk.

[...]

No wealth can buy the requisite leisure, freedom, and independence which are the capital in this profession... It requires a direct dispensation from Heaven to become a walker.

Thoreau's prescription, to be sure, is neither for the faint of body nor for the gainfully entrapped in the nine-to-five hamster wheel. Professing that the preservation of his "health and spirits" requires "sauntering through the woods and over the hills and fields" for at least four hours a day, he laments the fates of the less fortunate and leaves one wondering what he may have said of today's desk-bound office worker:

When sometimes I am reminded that the mechanics and shopkeepers stay in their shops not only all the forenoon, but all the afternoon too, sitting with crossed legs, so many of them – as if the legs were made to sit upon, and not to stand or walk upon – I think that they deserve some credit for not having all committed suicide long ago.

When sometimes I am reminded that the mechanics and shopkeepers stay in their shops not only all the forenoon, but all the afternoon too, sitting with crossed legs, so many of them – as if the legs were made to sit upon, and not to stand or walk upon – I think that they deserve some credit for not having all committed suicide long ago.

[...]

I am astonished at the power of endurance, to say nothing of the moral insensibility, of my neighbors who confine themselves to shops and offices the whole day for weeks and months, aye, and years almost together.

Of course, lest we forget, Thoreau was able to saunter through the woods and over the hills and fields in no small part thanks to support from his mom and sister, who fetched him fresh-baked donuts as he renounced civilization. In fact, he makes a sweetly compassionate aside, given the era he was writing in, about women's historical lack of mobility:

How womankind, who are confined to the house still more than men, stand it I do not know; but I have ground to suspect that most of them do not stand it at all.

How womankind, who are confined to the house still more than men, stand it I do not know; but I have ground to suspect that most of them do not stand it at all.

Thoreau is careful to point out that the walking he extols has nothing to do with transportational utility or physical exercise – rather it is a spiritual endeavor undertaken for its own sake:

The walking of which I speak has nothing in it akin to taking exercise, as it is called, as the sick take medicine at stated hours – as the Swinging of dumb-bells or chairs; but is itself the enterprise and adventure of the day. If you would get exercise, go in search of the springs of life. Think of a man's swinging dumbbells for his health, when those springs are bubbling up in far-off pastures unsought by him!

The walking of which I speak has nothing in it akin to taking exercise, as it is called, as the sick take medicine at stated hours – as the Swinging of dumb-bells or chairs; but is itself the enterprise and adventure of the day. If you would get exercise, go in search of the springs of life. Think of a man's swinging dumbbells for his health, when those springs are bubbling up in far-off pastures unsought by him!

Illustration by D. B. Johnson from Henry Hikes to Fitchburg

To engage in this kind of walking, Thoreau argues, we ought to reconnect with our wild nature:

When we walk, we naturally go to the fields and woods: what would become of us, if we walked only in a garden or a mall? ... Give me a wildness whose glance no civilization can endure – as if we lived on the marrow of koodoos devoured raw.

When we walk, we naturally go to the fields and woods: what would become of us, if we walked only in a garden or a mall? ... Give me a wildness whose glance no civilization can endure – as if we lived on the marrow of koodoos devoured raw.

[...]

Life consists with wildness. The most alive is the wildest.

[...]

All good things are wild and free.

One can only wonder how Thoreau would eviscerate this formidable set of civilizing regulations at Walden Pond, his beloved patch of wilderness. (Photograph: Karen Barbarossa)

But his most prescient point has to do with the idea that sauntering – like any soul-nourishing activity – should be approached with a mindset of presence rather than productivity. To think that a man who lived in a forest cabin in the middle of the 19th century might have such extraordinary insight into our toxic modern cult of busyness is hard to imagine, and yet he captures the idea that "busy is a decision" with astounding elegance:

I am alarmed when it happens that I have walked a mile into the woods bodily, without getting there in spirit. In my afternoon walk I would fain forget all my morning occupations and my obligations to Society. But it sometimes happens that I cannot easily shake off the village. The thought of some work will run in my head and I am not where my body is – I am out of my senses. In my walks I would fain return to my senses. What business have I in the woods, if I am thinking of something out of the woods?

I am alarmed when it happens that I have walked a mile into the woods bodily, without getting there in spirit. In my afternoon walk I would fain forget all my morning occupations and my obligations to Society. But it sometimes happens that I cannot easily shake off the village. The thought of some work will run in my head and I am not where my body is – I am out of my senses. In my walks I would fain return to my senses. What business have I in the woods, if I am thinking of something out of the woods?

Walking, which is available as a free ebook, is a brisk and immensely invigorating read in its entirety, as Thoreau goes on to explore the usefulness of useless knowledge, the uselessness of given names, and how private property is killing our capacity for wildness. Complement it with Maira Kalman on walking as a creative stimulant and the cognitive science of how a walk along a single city block can forever change the way you perceive the world.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

If you enjoyed this week's newsletter, please consider helping me keep it going with a small donation.