Hey bob sefcik! If you missed last week's edition – how melancholy expands our capacity for creativity, the best science books of the year, beautifully untranslatable words from around the world, Anne Lamott on grief, grace, and gratitude, and more – you can catch up right here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation – every little bit helps, and comes enormously appreciated. (NOTE: Most email programs get grumpy about messages exceeding a certain number of characters, so due to their length, some articles in this week's email digest have been truncated – you can read the full versions on the site by following the respective "READ MORE" links.)

Hey bob sefcik! If you missed last week's edition – how melancholy expands our capacity for creativity, the best science books of the year, beautifully untranslatable words from around the world, Anne Lamott on grief, grace, and gratitude, and more – you can catch up right here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation – every little bit helps, and comes enormously appreciated. (NOTE: Most email programs get grumpy about messages exceeding a certain number of characters, so due to their length, some articles in this week's email digest have been truncated – you can read the full versions on the site by following the respective "READ MORE" links.)

After the year's most intelligent and imaginative children's books and best science books, here are my favorite books on psychology and philosophy published this year, along with the occasional letter and personal essay – genres that, at their most excellent, offer hearty helpings of both disciplines. Perhaps more precisely, these are the year's finest books on how to live sane, creative, meaningful lives. (And since the subject is of the most timeless kind, revisit the selections 2013, 2012, and 2011.)

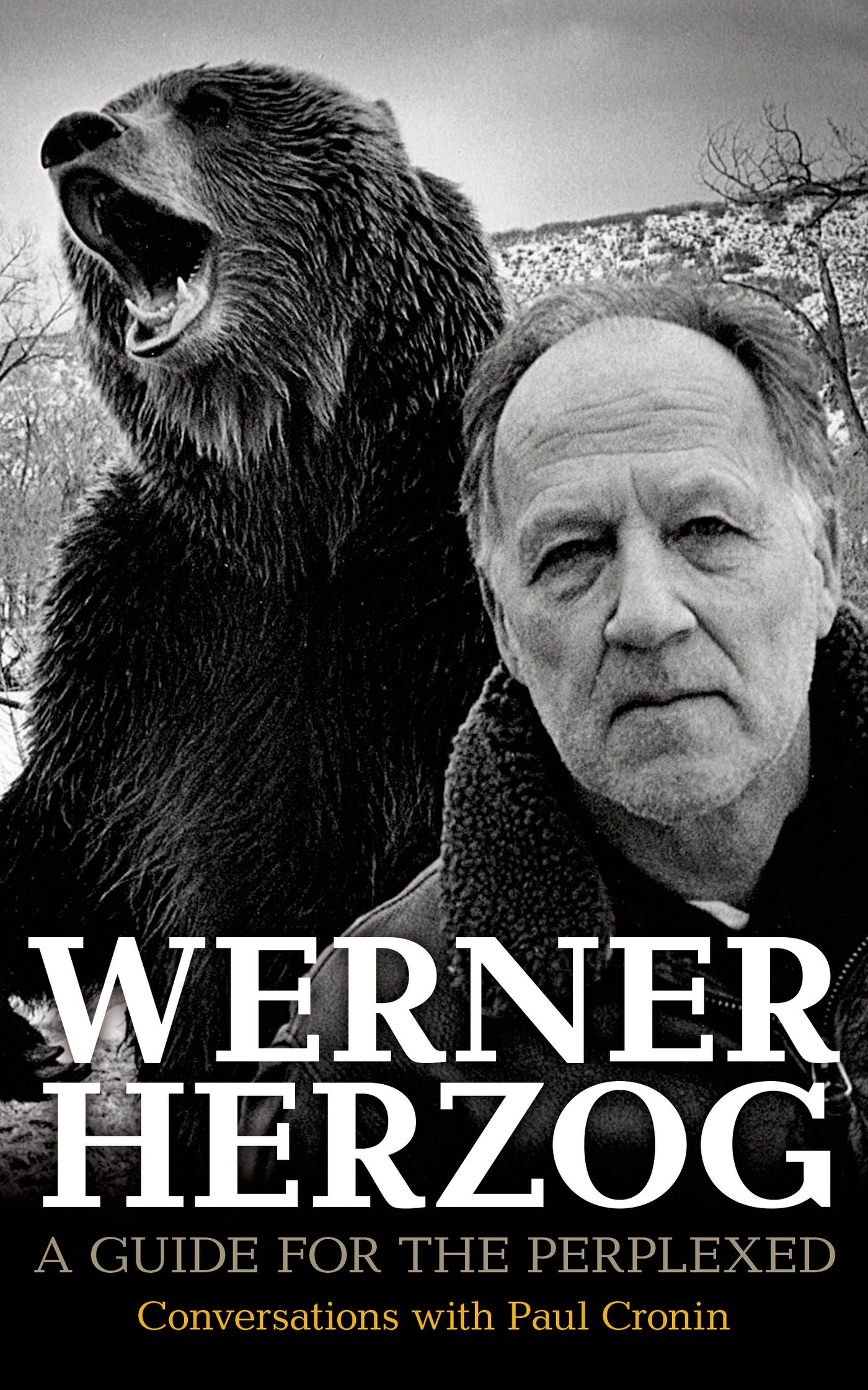

1. A GUIDE FOR THE PERPLEXED

Werner Herzog is celebrated as one of the most influential and innovative filmmakers of our time, but his ascent to acclaim was far from a straight trajectory from privilege to power. Abandoned by his father at an early age, Herzog survived a WWII bombing that demolished the house next door to his childhood home and was raised by a single mother in near-poverty. He found his calling in filmmaking after reading an encyclopedia entry on the subject as a teenager and took a job as a welder in a steel factory in his late teens to fund his first films. These building blocks of his character – tenacity, self-reliance, imaginative curiosity – shine with blinding brilliance in the richest and most revealing of Herzog's interviews. Werner Herzog: A Guide for the Perplexed (public library) – not to be confused with E.F. Schumacher's excellent 1978 philosophy book of the same title – presents the director's extensive, wide-ranging conversation with writer and filmmaker Paul Cronin. His answers are unfiltered and to-the-point, often poignant but always unsentimental, not rude but refusing to infest the garden of honest human communication with the Victorian-seeded, American-sprouted weed of pointless politeness.

Werner Herzog is celebrated as one of the most influential and innovative filmmakers of our time, but his ascent to acclaim was far from a straight trajectory from privilege to power. Abandoned by his father at an early age, Herzog survived a WWII bombing that demolished the house next door to his childhood home and was raised by a single mother in near-poverty. He found his calling in filmmaking after reading an encyclopedia entry on the subject as a teenager and took a job as a welder in a steel factory in his late teens to fund his first films. These building blocks of his character – tenacity, self-reliance, imaginative curiosity – shine with blinding brilliance in the richest and most revealing of Herzog's interviews. Werner Herzog: A Guide for the Perplexed (public library) – not to be confused with E.F. Schumacher's excellent 1978 philosophy book of the same title – presents the director's extensive, wide-ranging conversation with writer and filmmaker Paul Cronin. His answers are unfiltered and to-the-point, often poignant but always unsentimental, not rude but refusing to infest the garden of honest human communication with the Victorian-seeded, American-sprouted weed of pointless politeness.

Herzog's insights coalesce into a kind of manifesto for following one's particular calling, a form of intelligent, irreverent self-help for the modern creative spirit – indeed, even though Herzog is a humanist fully detached from religion, there is a strong spiritual undertone to his wisdom, rooted in what Cronin calls "unadulterated intuition" and spanning everything from what it really means to find your purpose and do what you love to the psychology and practicalities of worrying less about money to the art of living with presence with an age of productivity. As Cronin points out in the introduction, Herzog's thoughts collected in the book are "a decades-long outpouring, a response to the clarion call, to the fervent requests for guidance."

And yet in many ways, A Guide for the Perplexed could well have been titled A Guide to the Perplexed, for Herzog is as much a product of his "cumulative humiliations and defeats," as he himself phrases it, as of his own "chronic perplexity," to borrow E.B. White's unforgettable term – Herzog possesses that rare, paradoxical combination of absolute clarity of conviction and wholehearted willingness to inhabit his own inner contradictions, to pursue life's open-endedness with equal parts focus of vision and nimbleness of navigation.

A certain self-reliance that permeates his films and his mind, a refusal to let the fear of failure inhibit trying – a sensibility the voiceover in the final scene of Herzog's The Unprecedented Defence of the Fortress Deutschkreuz captures perfectly: "Even a defeat is better than nothing at all."

Sample this magnificent tome with Herzog on creativity, self-reliance, and making a living out of what you love and his no-bullshit advice to aspiring filmmakers, which applies just as brilliantly to any field of creative endeavor.

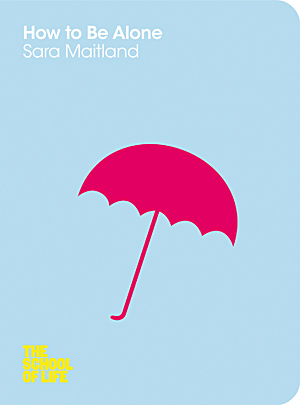

2. HOW TO BE ALONE

If the odds of finding one's soul mate are so dreadfully dismal and the secret of lasting love is largely a matter of concession, is it any wonder that a growing number of people choose to go solo? The choice of solitude, of active aloneness, has relevance not only to romance but to all human bonds – even Emerson, perhaps the most eloquent champion of friendship in the English language, lived a significant portion of his life in active solitude, the very state that enabled him to produce his enduring essays and journals. And yet that choice is one our culture treats with equal parts apprehension and contempt, particularly in our age of fetishistic connectivity. Hemingway's famous assertion that solitude is essential for creative work is perhaps so oft-cited precisely because it is so radical and unnerving in its proposition.

If the odds of finding one's soul mate are so dreadfully dismal and the secret of lasting love is largely a matter of concession, is it any wonder that a growing number of people choose to go solo? The choice of solitude, of active aloneness, has relevance not only to romance but to all human bonds – even Emerson, perhaps the most eloquent champion of friendship in the English language, lived a significant portion of his life in active solitude, the very state that enabled him to produce his enduring essays and journals. And yet that choice is one our culture treats with equal parts apprehension and contempt, particularly in our age of fetishistic connectivity. Hemingway's famous assertion that solitude is essential for creative work is perhaps so oft-cited precisely because it is so radical and unnerving in its proposition.

Solitude, the kind we elect ourselves, is met with judgment and enslaved by stigma. It is also a capacity absolutely essential for a full life.

That paradox is what British author Sara Maitland explores in How to Be Alone (public library | IndieBound) – the latest installment in The School of Life's thoughtful crusade to reclaim the traditional self-help genre in a series of intelligent, non-self-helpy yet immeasurably helpful guides to such aspects of modern living as finding fulfilling work, cultivating a healthier relationship with sex, worrying less about money, and staying sane.

While Maitland lives in a region of Scotland with one of the lowest population densities in Europe, where the nearest supermarket is more than twenty miles away and there is no cell service (pause on that for a moment), she wasn't always a loner – she grew up in a big, close-knit family as one of six children. It was only when she became transfixed by the notion of silence, the subject of her previous book, that she arrived, obliquely, at solitude. She writes:

I got fascinated by silence; by what happens to the human spirit, to identity and personality when the talking stops, when you press the off button, when you venture out into that enormous emptiness. I was interested in silence as a lost cultural phenomenon, as a thing of beauty and as a space that had been explored and used over and over again by different individuals, for different reasons and with wildly differing results. I began to use my own life as a sort of laboratory to test some ideas and to find out what it felt like. Almost to my surprise, I found I loved silence. It suited me. I got greedy for more. In my hunt for more silence, I found this valley and built a house here, on the ruins of an old shepherd's cottage.

I got fascinated by silence; by what happens to the human spirit, to identity and personality when the talking stops, when you press the off button, when you venture out into that enormous emptiness. I was interested in silence as a lost cultural phenomenon, as a thing of beauty and as a space that had been explored and used over and over again by different individuals, for different reasons and with wildly differing results. I began to use my own life as a sort of laboratory to test some ideas and to find out what it felt like. Almost to my surprise, I found I loved silence. It suited me. I got greedy for more. In my hunt for more silence, I found this valley and built a house here, on the ruins of an old shepherd's cottage.

Illustration by Marianne Dubuc from 'The Lion and the Bird,' one of the best children's books of the year

Maitland's interest in solitude, however, is somewhat different from that in silence – while private in its origin, it springs from a public-facing concern about the need to address "a serious social and psychological problem around solitude," a desire to "allay people's fears and then help them actively enjoy time spent in solitude." And so she does, posing the central, "slippery" question of this predicament:

Being alone in our present society raises an important question about identity and well-being...

Being alone in our present society raises an important question about identity and well-being...

How have we arrived, in the relatively prosperous developed world, at least, at a cultural moment which values autonomy, personal freedom, fulfillment and human rights, and above all individualism, more highly than they have ever been valued before in human history, but at the same time these autonomous, free, self-fulfilling individuals are terrified of being alone with themselves? ... We live in a society which sees high self-esteem as a proof of well-being, but we do not want to be intimate with this admirable and desirable person.

We see moral and social conventions as inhibitions on our personal freedoms, and yet we are frightened of anyone who goes away from the crowd and develops "eccentric" habits.

We believe that everyone has a singular personal "voice" and is, moreover, unquestionably creative, but we treat with dark suspicion (at best) anyone who uses one of the most clearly established methods of developing that creativity – solitude.

We think we are unique, special and deserving of happiness, but we are terrified of being alone... We are supposed now to seek our own fulfillment, to act on our feelings, to achieve authenticity and personal happiness – but mysteriously not do it on our own.

Today, more than ever, the charge carries both moral judgement and weak logic.

Maitland goes on to explore the underlying psychology of our unease from the fall of the Roman Empire to the rise of the "male spinster" and how to cultivate the five deepest rewards of solitude. Read more here.

3. WAKING UP

Nietzsche's famous proclamation that "God is dead" is among modern history's most oft-cited aphorisms, and yet as is often the case with its ilk, such quotations often miss the broader context in a way that bespeaks the lazy reductionism with which we tend to approach questions of spirituality today. Nietzsche himself clarified the full dimension of his statement six years later, in a passage from The Twilight of Idols, where he explained that "God" simply signified the supersensory realm, or "true world," and wrote: "We have abolished the true world. What has remained? The apparent one perhaps? Oh no! With the true world we have also abolished the apparent one."

Nietzsche's famous proclamation that "God is dead" is among modern history's most oft-cited aphorisms, and yet as is often the case with its ilk, such quotations often miss the broader context in a way that bespeaks the lazy reductionism with which we tend to approach questions of spirituality today. Nietzsche himself clarified the full dimension of his statement six years later, in a passage from The Twilight of Idols, where he explained that "God" simply signified the supersensory realm, or "true world," and wrote: "We have abolished the true world. What has remained? The apparent one perhaps? Oh no! With the true world we have also abolished the apparent one."

Indeed, this struggle to integrate the sensory and the supersensory, the physical and the metaphysical, has been addressed with varying degrees of sensitivity by some of history's greatest minds – reflections like Carl Sagan on science and religion, Flannery O'Connor on dogma, belief, and the difference between religion and faith, Alan Lightman on science and spirituality, Albert Einstein on whether scientists pray, Ada Lovelace on the interconnectedness of everything, Alan Watts on the difference between belief and faith, C.S. Lewis on the paradox of free will, and Jane Goodall on science and spirit.

In Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality Without Religion (public library | IndieBound), philosopher, neuroscientist, and mindful skeptic Sam Harris offers a contemporary addition to this lineage of human inquiry – an extraordinary and ambitious masterwork of such integration between science and spirituality, which Harris himself describes as "by turns a seeker's memoir, an introduction to the brain, a manual of contemplative instruction, and a philosophical unraveling of what most people consider to be the center of their inner lives." Or, perhaps most aptly, an effort "to pluck the diamond from the dunghill of esoteric religion."

Harris begins by recounting an experience he had at age sixteen – a three-day wilderness retreat designed to spur spiritual awakening of some sort, which instead left young Harris feeling like the contemplation of the existential mystery in the presence of his own company was "a source of perfect misery." This frustrating experience became "a sufficient provocation" that launched him into a lifelong pursuit of the kinds of transcendent experiences that gave rise to the world's major spiritual traditions, examining them instead with a scientist's vital blend of skepticism and openness and a philosopher's aspiration to be "scrupulously truthful."

Harris writes:

Our minds are all we have. They are all we have ever had. And they are all we can offer others... Every experience you have ever had has been shaped by your mind. Every relationship is as good or as bad as it is because of the minds involved.

Our minds are all we have. They are all we have ever had. And they are all we can offer others... Every experience you have ever had has been shaped by your mind. Every relationship is as good or as bad as it is because of the minds involved.

Noting that the entirety of our experience, as well as our satisfaction with that experience, is filtered through our minds – "If you are perpetually angry, depressed, confused, and unloving, or your attention is elsewhere, it won't matter how successful you become or who is in your life – you won't enjoy any of it." – Harris sets out to reconcile the quest to achieve one's goals with a deeper longing, a recognition, perhaps, that presence is far more rewarding than productivity. He writes:

Most of us spend our time seeking happiness and security without acknowledging the underlying purpose of our search. Each of us is looking for a path back to the present: We are trying to find good enough reasons to be satisfied now.

Most of us spend our time seeking happiness and security without acknowledging the underlying purpose of our search. Each of us is looking for a path back to the present: We are trying to find good enough reasons to be satisfied now.

Acknowledging that this is the structure of the game we are playing allows us to play it differently. How we pay attention to the present moment largely determines the character of our experience and, therefore, the quality of our lives.

This message, of course, is nothing new – half a century ago, Alan Watts made a spectacular case for it, building on millennia of Eastern philosophy. But what makes our era singular and this discourse particularly timely, Harris points out, is that there is now a growing body of scientific research substantiating these ancient intuitions, which he goes on to examine in fascinating detail.

Sample the book further with Harris on the paradox of meditation.

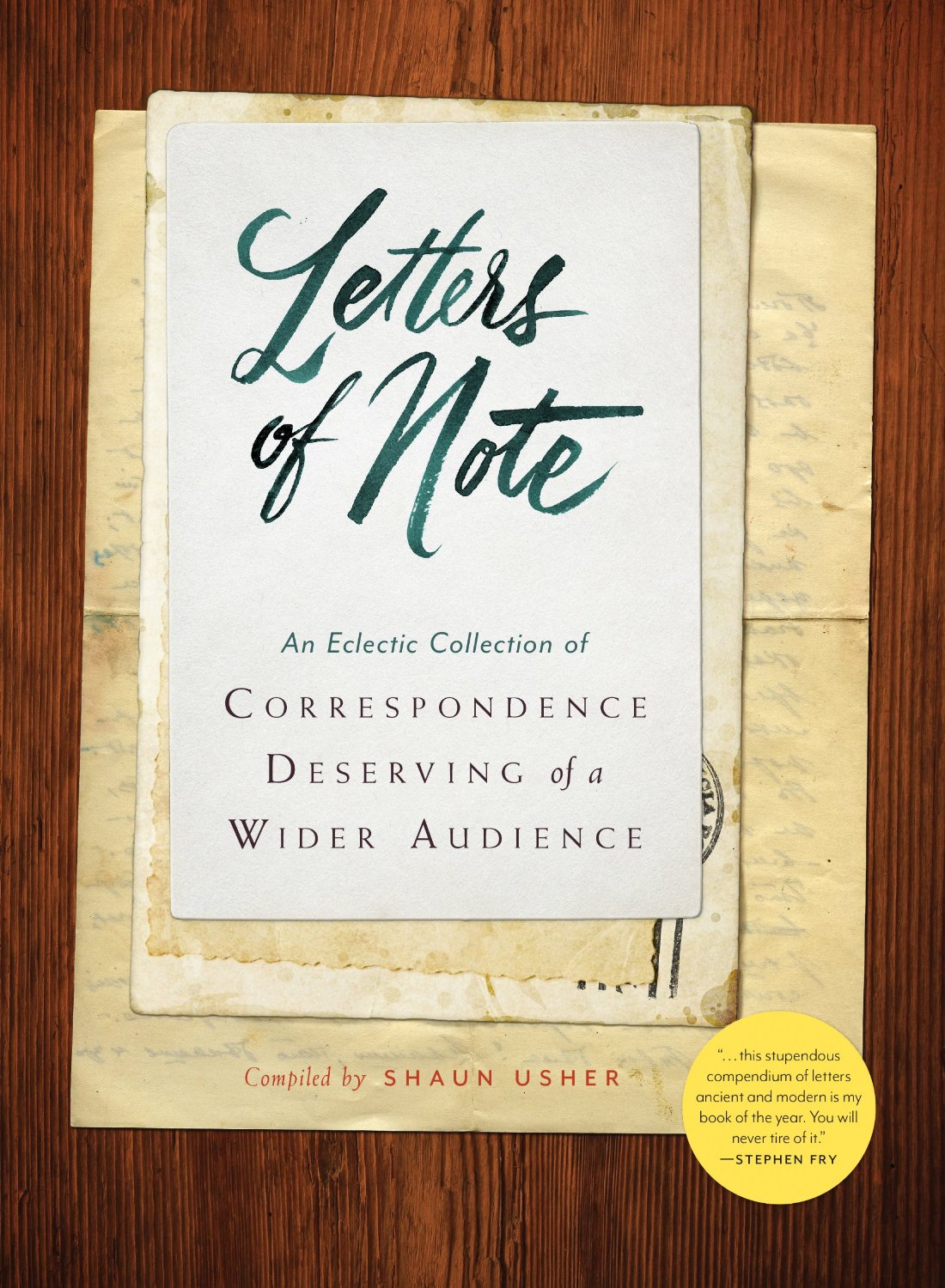

4. LETTERS OF NOTE

Virginia Woolf called letter-writing "the humane art" – an epithet only amplified today, in an age when we so frequently mistake reaction for response and succumb to expectations of immediacy that render impossible the beautiful, contemplative mutuality at the heart of the notion of co-respondence. This, perhaps, is why yesteryear's greatest letters appeal to us more irrepressibly than ever.

Virginia Woolf called letter-writing "the humane art" – an epithet only amplified today, in an age when we so frequently mistake reaction for response and succumb to expectations of immediacy that render impossible the beautiful, contemplative mutuality at the heart of the notion of co-respondence. This, perhaps, is why yesteryear's greatest letters appeal to us more irrepressibly than ever.

For years, Shaun Usher has been unearthing and highlighting brilliant, funny, poignant, exquisitely human letters from luminaries and ordinary people alike on his magnificent website. This year, the best of them were released in Letters of Note: Correspondence Deserving of a Wider Audience (public library | IndieBound) – the aptly titled, superb collection featuring contributions from such cultural icons as Virginia Woolf, Roald Dahl, Louis Armstrong, Kurt Vonnegut, Nick Cave, Richard Feynman, Jack Kerouac, and more.

Sample this treasure trove further with E.B. White's beautiful letter to a man who had lost faith in humanity, young Hunter S. Thompson's advice to a friend on how to find one's purpose and live a full life, comedian Bill Hicks's piercing missive to a censoring priest on what freedom of speech really means, and Eudora Welty's disarming job application to the New Yorker.

:: SEE NUMBERS 5-8

9. THE ART OF ASKING

"Have compassion for everyone you meet, even if they don't want it," Lucinda Williams sang from my headphones into my heart one rainy October morning on the train to Hudson. "What seems cynicism is always a sign, always a sign..." I was headed to Hudson for a conversation with a very different but no less brilliant musician, and a longtime kindred spirit – the talented and kind Amanda Palmer. In an abandoned schoolhouse across the street from her host's home, we sat down to talk about her magnificent and culturally necessary new book, The Art of Asking: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Let People Help (public library | IndieBound) – a beautifully written inquiry into why we have such a hard time accepting compassion in all of its permutations, from love to what it takes to make a living, what lies behind our cynicism in refusing it, and how learning to accept it makes possible the greatest gifts of our shared humanity.

"Have compassion for everyone you meet, even if they don't want it," Lucinda Williams sang from my headphones into my heart one rainy October morning on the train to Hudson. "What seems cynicism is always a sign, always a sign..." I was headed to Hudson for a conversation with a very different but no less brilliant musician, and a longtime kindred spirit – the talented and kind Amanda Palmer. In an abandoned schoolhouse across the street from her host's home, we sat down to talk about her magnificent and culturally necessary new book, The Art of Asking: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Let People Help (public library | IndieBound) – a beautifully written inquiry into why we have such a hard time accepting compassion in all of its permutations, from love to what it takes to make a living, what lies behind our cynicism in refusing it, and how learning to accept it makes possible the greatest gifts of our shared humanity.

I am partial, perhaps, because my own sustenance depends on accepting help. But I also deeply believe and actively partake in both the yin and the yang of that vitalizing osmosis of giving and receiving that keeps today's creative economy alive, binding artists and audiences, writers and readers, musicians and fans, into the shared cause of creative culture. "It's only when we demand that we are hurt," Henry Miller wrote in contemplating the circles of giving and receiving in 1942, but we still seem woefully caught in the paradoxical trap of too much entitlement to what we feel we want and too little capacity to accept what we truly need. The unhinging of that trap is what Amanda explores with equal parts deep personal vulnerability, profound insight into the private and public lives of art, and courageous conviction about the future of creative culture.

The most urgent clarion call echoing throughout the book, which builds on Amanda's terrific TED talk, is for loosening our harsh and narrow criteria for what it means to be an artist, and, most of all, for undoing our punishing ideas about what renders one a not-artist, or – worse yet – a not-artist-enough. Amanda writes of the anguishing Impostor Syndrome epidemic such limiting notions spawn:

People working in the arts engage in street combat with The Fraud Police on a daily basis, because much of our work is new and not readily or conventionally categorized. When you're an artist, nobody ever tells you or hits you with the magic wand of legitimacy. You have to hit your own head with your own handmade wand. And you feel stupid doing it.

People working in the arts engage in street combat with The Fraud Police on a daily basis, because much of our work is new and not readily or conventionally categorized. When you're an artist, nobody ever tells you or hits you with the magic wand of legitimacy. You have to hit your own head with your own handmade wand. And you feel stupid doing it.

There's no "correct path" to becoming a real artist. You might think you'll gain legitimacy by going to university, getting published, getting signed to a record label. But it's all bullshit, and it's all in your head. You're an artist when you say you are. And you're a good artist when you make somebody else experience or feel something deep or unexpected.

Read more and watch my conversation with Palmer here.

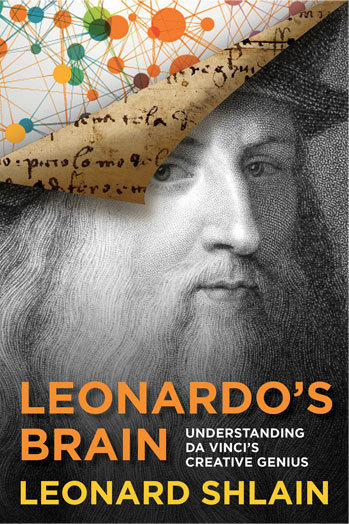

10. LEONARDO'S BRAIN

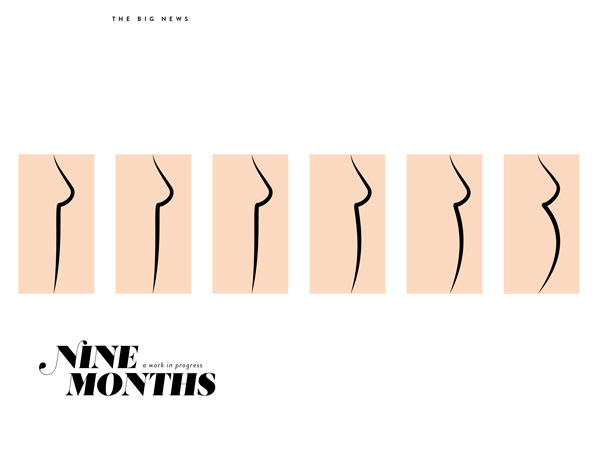

One September day in 2008, Leonard Shlain found himself having trouble buttoning his shirt with his right hand. He was admitted into the emergency room, diagnosed with Stage 4 brain cancer, and given nine months to live. Shlain – a surgeon by training and a self-described "synthesizer by nature" with an intense interest in the ennobling intersection of art and science, author of the now-legendary Art & Physics – had spent the previous seven years working on what he considered his magnum opus: a sort of postmortem brain scan of Leonardo da Vinci, performed six centuries after his death and fused with a detective story about his life, exploring what the unique neuroanatomy of the man commonly considered humanity's greatest creative genius might reveal about the essence of creativity itself.

One September day in 2008, Leonard Shlain found himself having trouble buttoning his shirt with his right hand. He was admitted into the emergency room, diagnosed with Stage 4 brain cancer, and given nine months to live. Shlain – a surgeon by training and a self-described "synthesizer by nature" with an intense interest in the ennobling intersection of art and science, author of the now-legendary Art & Physics – had spent the previous seven years working on what he considered his magnum opus: a sort of postmortem brain scan of Leonardo da Vinci, performed six centuries after his death and fused with a detective story about his life, exploring what the unique neuroanatomy of the man commonly considered humanity's greatest creative genius might reveal about the essence of creativity itself.

Shlain finished the book on May 3, 2009. He died a week later. His three children – Kimberly, Jordan, and filmmaker Tiffany Shlain – spent the next five years bringing their father's final legacy to life. The result is Leonardo's Brain: Understanding Da Vinci's Creative Genius (public library | IndieBound) – an astonishing intellectual, and at times spiritual, journey into the center of human creativity via the particular brain of one undereducated, left-handed, nearly ambidextrous, vegetarian, pacifist, gay, singularly creative Renaissance male, who Shlain proposes was able to attain a different state of consciousness than "practically all other humans."

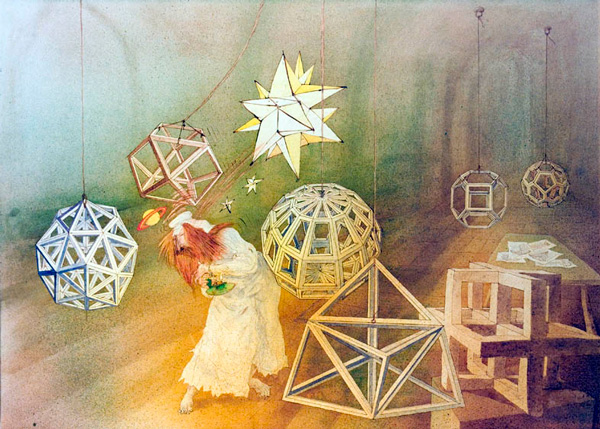

Illustration by Ralph Steadman from I, Leonardo

Noting that "a writer is always refining his ideas," Shlain points out that the book is a synthesis of his three previous books, and an effort to live up to Kafka's famous proclamation that "a book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us." It is also a beautiful celebration of the idea that art and science belong together and enrich one another whenever they converge.

Shlain argues that Leonardo – who painted the eternally mysterious Mona Lisa, created visionary anatomical drawings long before medical anatomy existed, made observations of bird flight in greater detailed than any previous scientist, mastered engineering, architecture, mathematics, botany, and cartography, might be considered history's first true scientist long before Mary Somerville coined the word, presaged Newton's Third Law, Bernoulli's law, and elements of chaos theory, and was a deft composer who sang "divinely," among countless other domains of mastery – is the individual most worthy of the title "genius" in both science and art:

The divergent flow of art and science in the historical record provides evidence of a distinct compartmentalization of genius. The river of art rarely intersected with the meander of science.

The divergent flow of art and science in the historical record provides evidence of a distinct compartmentalization of genius. The river of art rarely intersected with the meander of science.

[...]

Although both art and science require a high degree of creativity, the difference between them is stark. For visionaries to change the domain of art, they must make a breakthrough that can only be judged through the lens of posterity. Great science, on the other hand, must be able to predict the future. If a scientist's hypotheses cannot be turned into a law that can be verified by future investigators, it is not scientifically sound. Another contrast: Art and science represent the difference between "being" and "doing." Art's raison d'être is to evoke an emotion. Science seeks to solve problems by advancing knowledge.

[...]

Leonardo's story continues to compel because he represents the highest excellence all of us lesser mortals strive to achieve – to be intellectually, creatively, and emotionally well-rounded. No other individual in the known history of the human species attained such distinction both in science and art as the hyper-curious, undereducated, illegitimate country boy from Vinci.

Using a wealth of available information from Leonardo's notebooks, various biographical resources, and some well-reasoned speculation, Shlain goes on to perform a "posthumous brain scan" seeking to illuminate the unique wiring of Da Vinci's brain and how it explains his unparalleled creativity.

Peek inside his findings here.

:: SEE FULL LIST 1–14 / SHARE ::

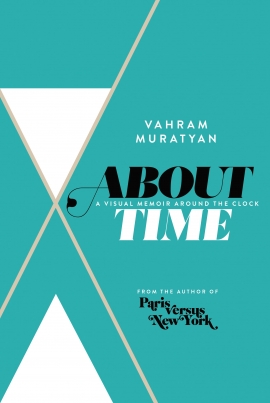

"I can see no reason to be bound by chronological time," Jeanette Winterson wrote in her spectacular essay on time and language. "As far as we know, the universe is not bound by it." And yet ever since Galileo invented modern timekeeping, the tyranny of the clock has not only bound but shackled us to the invisible dimension in everything from our internal rhythms to our ideal creative routines. Meanwhile, time, with its remarkable elasticity, continues to mystify us – unsurprisingly, perhaps, given that the capacity to imagine it made us human.

"I can see no reason to be bound by chronological time," Jeanette Winterson wrote in her spectacular essay on time and language. "As far as we know, the universe is not bound by it." And yet ever since Galileo invented modern timekeeping, the tyranny of the clock has not only bound but shackled us to the invisible dimension in everything from our internal rhythms to our ideal creative routines. Meanwhile, time, with its remarkable elasticity, continues to mystify us – unsurprisingly, perhaps, given that the capacity to imagine it made us human.

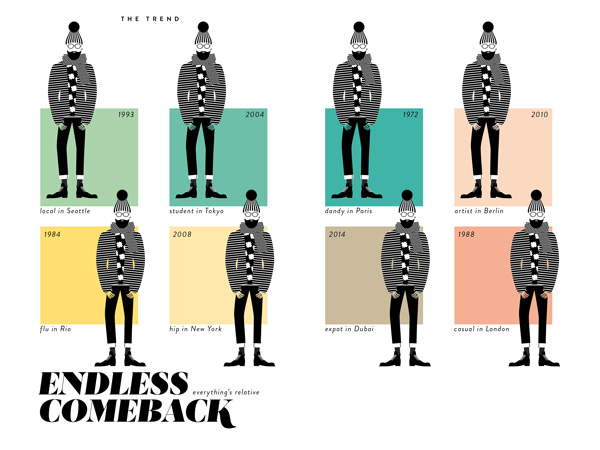

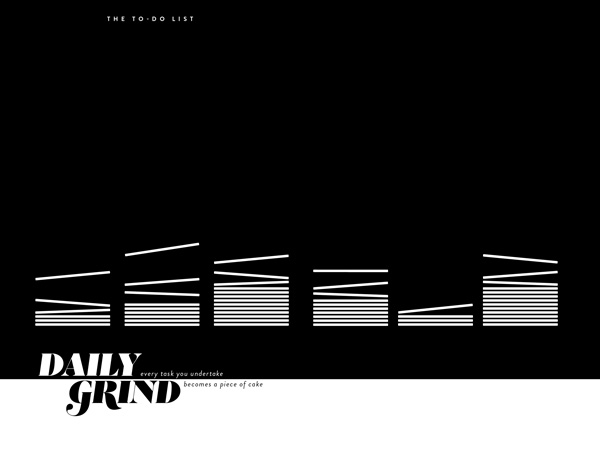

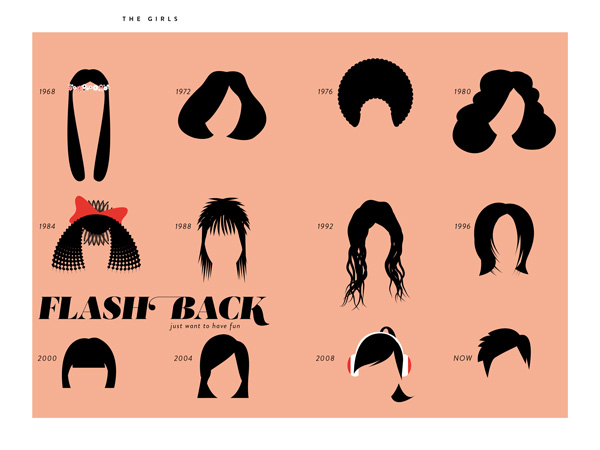

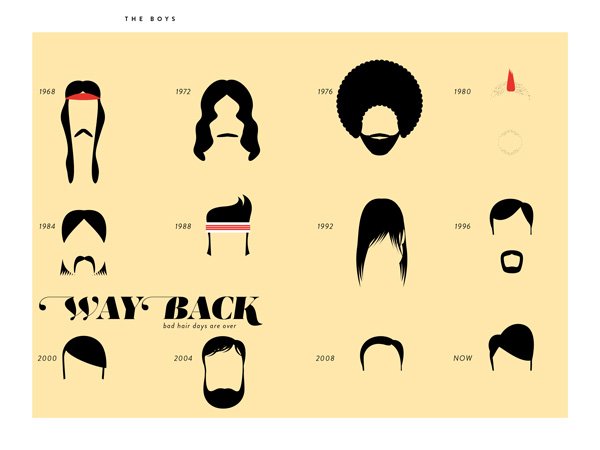

In About Time: A Visual Memoir Around the Clock (public library | IndieBound), French-Armenian graphic designer Vahram Muratyan – who gave us the 2012 delight Paris vs. New York – builds on humanity's long history of visualizing time, exploring its enduring mesmerism with great humor, sensitivity, and insight into modern life.

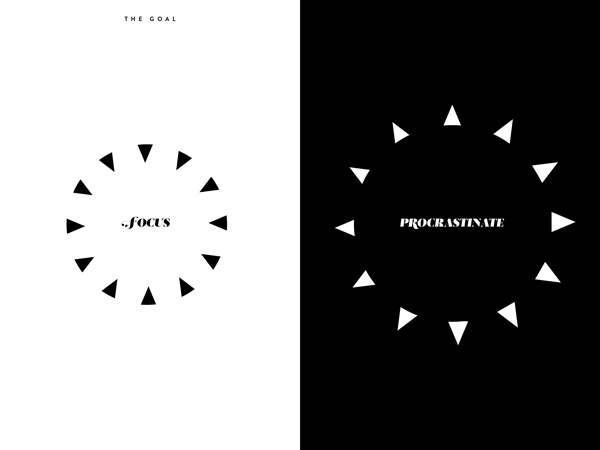

From the predictable cycles of our routines, relationships, and our fashions to our psychological tussles with the flow of life, Muratyan captures the profound anticipatory anxiety that defines our relationship with time – the expectation that there is always something more, or more important, to do, that the next moment must bring what this one lacks. He pokes gentle fun at our preoccupation with productivity at the expense of presence and at the chronic civilizational busyness making us forget that, in the unforgettable words of Annie Dillard, "how we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives."

One can almost hear Alan Watts's voice booming from Muratyan's minimalist vignettes, admonishing once more that "hurrying and delaying are alike ways of trying to resist the present."

There is also a meta-element commenting on the cyclical nature of time and our resistance to its flow – Muratyan's visual sensibility is intentionally reminiscent of mid-century graphic design, vintage children's books, and the aesthetic of the Mad Men era, as if to remind us that nostalgia is our most stubborn and wistful hedge against time's merciless forward motion.

Although his project is undeniably intended to delight with visual humor, Muratyan rewards those willing to attend to what remains after the initial chuckle – a number of his vignettes explore the darker reaches of our relationship with time, reminding us that despite all of our efforts to control and constrain it, time itself inevitably has the upper hand in that play-pretend power dynamic.

In our recent conversation at Brooklyn's BookCourt, Muratyan and I dove deeper into the heart of the project by discussing how the tyranny of the clock has enslaved our capacity for spontaneity and presence, why the a-ha! moments of creative breakthrough arrive when we least expect them, the relationship between motion and meditative contemplation, and how life's most challenging experiences demolish all of our defenses and control strategies, leaving time as our only master. Please enjoy.

Complement About Time with Alan Watts on the art of timing, a visual history of mapping time and the psychology of why time slows down when we're afraid, speeds up as we age, and gets warped while we vacation, then counter the frantic modern rhythms Muratyan teases with a lesson in stillness from Leonard Cohen.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

"Someone has a great fire in his soul and nobody ever comes to warm themselves at it, and passers-by see nothing but a little smoke at the top of the chimney," young Vincent van Gogh wrote in a letter as he floundered to find his purpose. For the century and a half since, and undoubtedly the many centuries before, the question of how to kindle that soul-warming fire by finding one's purpose and making a living out of meaningful work has continued to frustrate not only the young, not only aspiring artists, but people of all ages, abilities, and walks of life. How to navigate that existential maze with grace is what Parker J. Palmer – founder of the Center for Courage & Renewal and a man of great insight into the elusive art of inner wholeness – explores with compassionate warmth and wisdom in his 1999 book Let Your Life Speak: Listening for the Voice of Vocation (public library | IndieBound).

"Someone has a great fire in his soul and nobody ever comes to warm themselves at it, and passers-by see nothing but a little smoke at the top of the chimney," young Vincent van Gogh wrote in a letter as he floundered to find his purpose. For the century and a half since, and undoubtedly the many centuries before, the question of how to kindle that soul-warming fire by finding one's purpose and making a living out of meaningful work has continued to frustrate not only the young, not only aspiring artists, but people of all ages, abilities, and walks of life. How to navigate that existential maze with grace is what Parker J. Palmer – founder of the Center for Courage & Renewal and a man of great insight into the elusive art of inner wholeness – explores with compassionate warmth and wisdom in his 1999 book Let Your Life Speak: Listening for the Voice of Vocation (public library | IndieBound).

In his own youth, Palmer had come to know intimately the soul-splitting rift between being good at one's work and being fulfilled in one's purpose. As an aspiring "ad man" in the Mad Men era, lured by "the fast car and other large toys that seemed to be the accessories [of] selfhood" – something supplanted today, perhaps, by the startup-lifestyle fetishism afflicting many young people – he awoke one day to a distinct and chilling realization:

The life I am living is not the same as the life that wants to live in me.

The life I am living is not the same as the life that wants to live in me.

Speaking to the notion that a large part of success is defining it for ourselves, and defining it in terms as close to Thoreau's as possible, Palmer reflects on his youth:

I lined up the loftiest ideals I could find and set out to achieve them. The results were rarely admirable, often laughable, and sometimes grotesque... I had simply found a "noble" way to live a life that was not my own, a life spent imitating heroes instead of listening to my heart...

I lined up the loftiest ideals I could find and set out to achieve them. The results were rarely admirable, often laughable, and sometimes grotesque... I had simply found a "noble" way to live a life that was not my own, a life spent imitating heroes instead of listening to my heart...

My youthful understanding of "Let your life speak" led me to conjure up the highest values I could imagine and then try to conform my life to them whether they were mine or not. If that sounds like what we are supposed to do with values, it is because that is what we are too often taught. There is a simplistic brand of moralism among us that wants to reduce the ethical life to making a list, checking it twice – against the index in some best-selling book of virtues, perhaps – and then trying very hard to be not naughty but nice.

There may be moments in life when we are so unformed that we need to use values like an exoskeleton to keep us from collapsing. But something is very wrong if such moments recur often in adulthood. Trying to live someone else's life, or to live by an abstract norm, will invariably fail – and may even do great damage.

Illustration from Herman and Rosie by Gus Gordon

Thirty years later, he arrives at a deeper, more ennobling, hard-earned interpretation of the old Quaker phrase after which the book is titled:

Before you tell your life what you intend to do with it, listen for what it intends to do with you. Before you tell your life what truths and values you have decided to live up to, let your life tell you what truths you embody, what values you represent.

Before you tell your life what you intend to do with it, listen for what it intends to do with you. Before you tell your life what truths and values you have decided to live up to, let your life tell you what truths you embody, what values you represent.

To be sure, this way of relating to life isn't about passivity or resignation or an illusory belief in fatedness, but about deconditioning our tendency to try to bend the world to our will and instead hear the quieter, deeper voices that speak to us from behind the ego's proclamations of will. In fact, the disposition Palmer advocates is something akin to Jeanette Winterson's notion of "active surrender" – the same paradoxical state we need to attain in order to experience the transformational power of art appears to be the one needed in discerning our true vocation. Palmer writes:

If the self seeks not pathology but wholeness, as I believe it does, then the willful pursuit of vocation is an act of violence toward ourselves – violence in the name of a vision that, however lofty, is forced on the self from without rather than grown from within. True self, when violated, will always resist us, sometimes at great cost, holding our lives in check until we honor its truth. Vocation does not come from willfulness. It comes from listening. I must listen to my life and try to understand what it is truly about – quite apart from what I would like it to be about – or my life will never represent anything real in the world, no matter how earnest my intentions.

If the self seeks not pathology but wholeness, as I believe it does, then the willful pursuit of vocation is an act of violence toward ourselves – violence in the name of a vision that, however lofty, is forced on the self from without rather than grown from within. True self, when violated, will always resist us, sometimes at great cost, holding our lives in check until we honor its truth. Vocation does not come from willfulness. It comes from listening. I must listen to my life and try to understand what it is truly about – quite apart from what I would like it to be about – or my life will never represent anything real in the world, no matter how earnest my intentions.

Listening, Palmer suggests, is a matter of shaking off the tyranny of "should" – whether socially imposed or self-inflicted. He offers a beautiful definition of what vocation really means and what it stands to give:

Vocation does not mean a goal that I pursue. It means a calling that I hear. Before I can tell my life what I want to do with it, I must listen to my life telling the who I am. I must listen for the truths and values at the heart of my own identity, not the standards by which I must live – but the standards by which I cannot help but live if I am living my own life.

Vocation does not mean a goal that I pursue. It means a calling that I hear. Before I can tell my life what I want to do with it, I must listen to my life telling the who I am. I must listen for the truths and values at the heart of my own identity, not the standards by which I must live – but the standards by which I cannot help but live if I am living my own life.

In a sentiment reminiscent of Thoreau's famous lament about borrowed opinions and one particularly poignant in our culture of confusing repetition and regurgitation for reflection and integration, Palmer adds:

We listen for guidance everywhere except from within.

We listen for guidance everywhere except from within.

And yet, Palmer cautions, what we hear might not always be a mellifluous serenade by our highest selves – but giving voice to the parts of ourselves we least like is essential to the process:

My life is not only about my strengths and virtues; it is also about my liabilities and my limits, my trespasses and my shadow. An inevitable though often ignored dimension of the quest for "wholeness" is that we must embrace what we dislike or find shameful about ourselves as well as what we are confident and proud of.

My life is not only about my strengths and virtues; it is also about my liabilities and my limits, my trespasses and my shadow. An inevitable though often ignored dimension of the quest for "wholeness" is that we must embrace what we dislike or find shameful about ourselves as well as what we are confident and proud of.

Let's take a necessary pause here to acknowledge that few words in our culture elicit more cynicism when mentioned publicly and more profound longing when contemplated privately than "soul." We wince at soul-speak as the stuff of misguided mystics or, worse yet, motivational speakers. And yet hardly anyone with even the slightest semblance of aspiration toward happiness can deny the existence of this delicately sensitive, stubbornly resilient core of our humanity. What makes Palmer's writing – Palmer's mind – especially enchanting is the tenderness with which he holds both sides of this cultural duality, yet remains unflinchingly on the side of the soul:

In our culture, we tend to gather information in ways that do not work very well when the source is the human soul: the soul is not responsive to subpoenas or cross-examinations. At best it will stand in the dock only long enough to plead the Fifth Amendment. At worst it will jump bail and never be heard from again. The soul speaks its truth only under quiet, inviting, and trustworthy conditions.

In our culture, we tend to gather information in ways that do not work very well when the source is the human soul: the soul is not responsive to subpoenas or cross-examinations. At best it will stand in the dock only long enough to plead the Fifth Amendment. At worst it will jump bail and never be heard from again. The soul speaks its truth only under quiet, inviting, and trustworthy conditions.

The soul is like a wild animal – tough, resilient, savvy, self-sufficient, and yet exceedingly shy. If we want to see a wild animal, the last thing we should do is to go crashing through the woods, shouting for the creature to come out. But if we are willing to walk quietly into the woods and sit silently for an hour or two at the base of a tree, the creature we are waiting for may well emerge, and out of the corner of an eye we will catch a glimpse of the precious wildness we seek.

With gentle compassion for our tendency to begin twenty years too late, Palmer writes:

What a long time it can take to become the person one has always been! How often in the process we mask ourselves in faces that are not our own. How much dissolving and shaking of ego we must endure before we discover our deep identity – the true self within every human being that is the seed of authentic vocation.

What a long time it can take to become the person one has always been! How often in the process we mask ourselves in faces that are not our own. How much dissolving and shaking of ego we must endure before we discover our deep identity – the true self within every human being that is the seed of authentic vocation.

He issues an especially passionate admonition against buying into the myth that a vocation is something bestowed upon us by an external force, some booming voice outside ourselves that does the "calling." Instead, echoing Picasso's proclamation that "one must have the courage of one's vocation and the courage to make a living from one's vocation," he dismisses such misleading models of externalizing the quest for a calling:

That concept of vocation is rooted in a deep distrust of selfhood, in the belief that the sinful self will always be "self-ish" unless corrected by external forces of virtue. It is a notion that made me feel inadequate to the task of living my own life, creating guilt about the distance between who I was and who I was supposed to be, leaving me exhausted as I labored to close the gap.

That concept of vocation is rooted in a deep distrust of selfhood, in the belief that the sinful self will always be "self-ish" unless corrected by external forces of virtue. It is a notion that made me feel inadequate to the task of living my own life, creating guilt about the distance between who I was and who I was supposed to be, leaving me exhausted as I labored to close the gap.

Today I understand vocation quite differently – not as a goal to be achieved but as a gift to be received. Discovering vocation does not mean scrambling toward some prize just beyond my reach but accepting the treasure of true self I already possess. Vocation does not come from a voice "out there" calling me to become something I am not. It comes from a voice "in here" calling me to be the person I was born to be.

And yet, Palmer is careful to acknowledge, accepting that innermost gift "turns out to be even more demanding than attempting to become someone else" – overwhelmed by its demands, we often hide or flee from it, bury it in busywork, or simply ignore it. But, reflecting on his granddaughter's distinct personality even as a baby, he assures that this gift is in each of us awaiting discovery:

We are disabused of original giftedness in the first half of our lives. Then – if we are awake, aware, and able to admit our loss – we spend the second half trying to recover and reclaim the gift we once possessed.

We are disabused of original giftedness in the first half of our lives. Then – if we are awake, aware, and able to admit our loss – we spend the second half trying to recover and reclaim the gift we once possessed.

Let Your Life Speak remains an indispensable read. Complement it with philosopher Roman Krznaric on how to find fulfilling work and some thoughts on making a living of doing what you love, then revisit Palmer on the art of inner wholeness.

:: MORE / SHARE ::

"It gives me such a sense of peace to draw; more than prayer, walks, anything," Sylvia Plath wrote in her diary when she first began working on her little-known drawings. "The great benefit of drawing … is that when you look at something, you see it for the first time," the great Milton Glaser observed in sharing his wisdom on life. "And you can spend your life without ever seeing anything."

"It gives me such a sense of peace to draw; more than prayer, walks, anything," Sylvia Plath wrote in her diary when she first began working on her little-known drawings. "The great benefit of drawing … is that when you look at something, you see it for the first time," the great Milton Glaser observed in sharing his wisdom on life. "And you can spend your life without ever seeing anything."

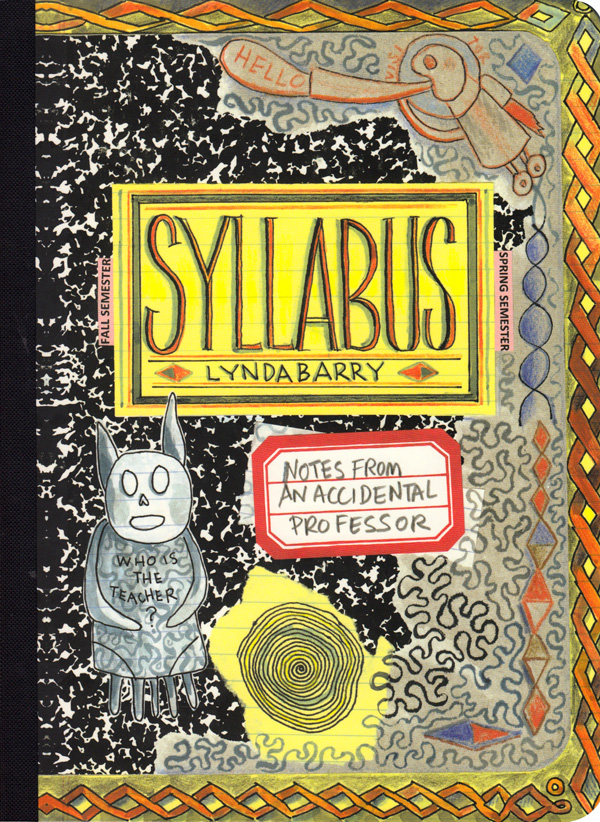

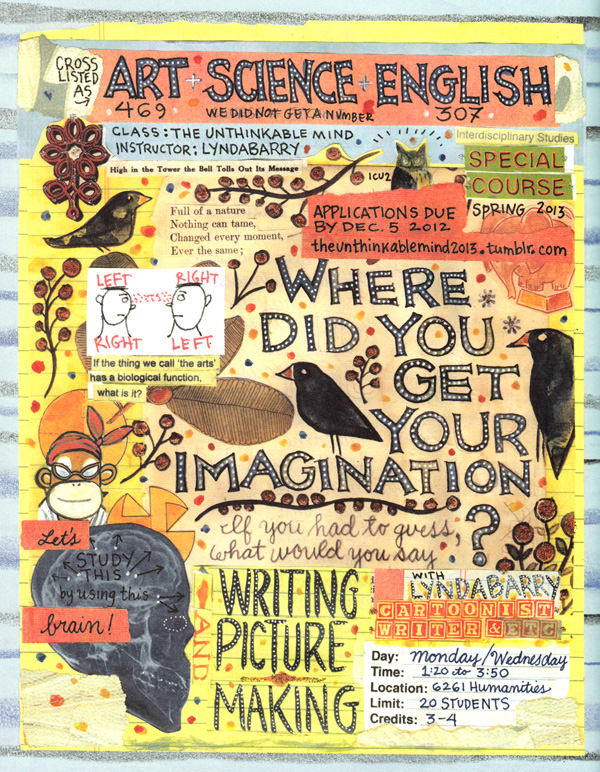

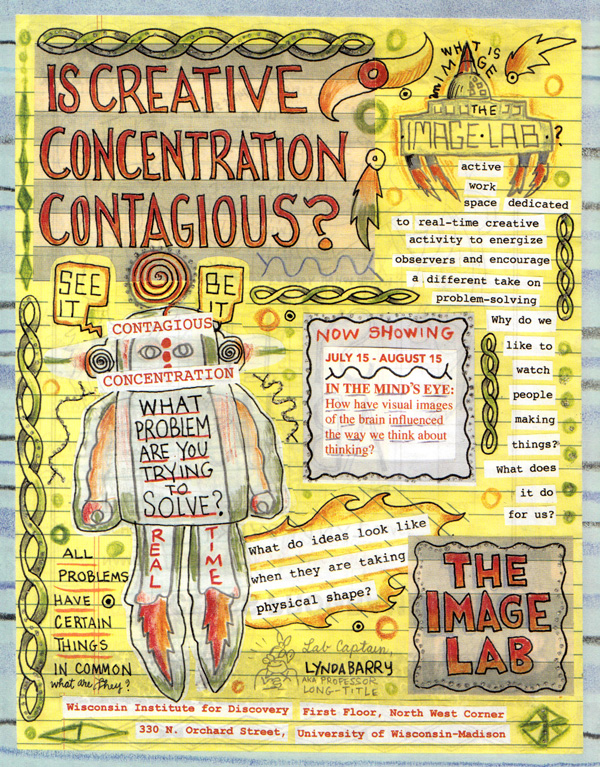

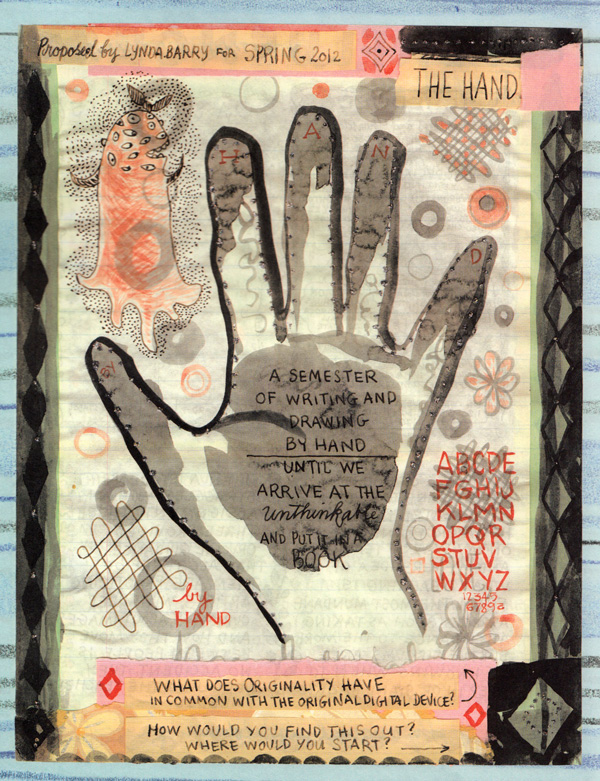

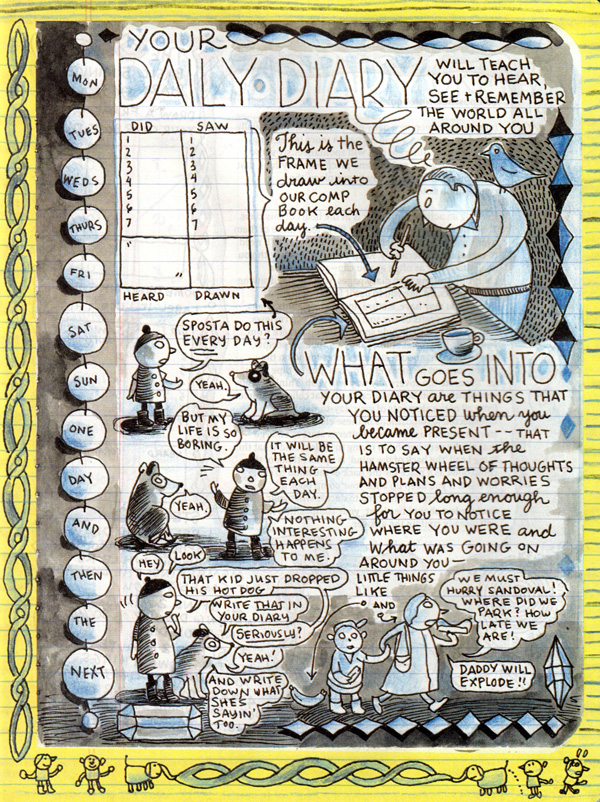

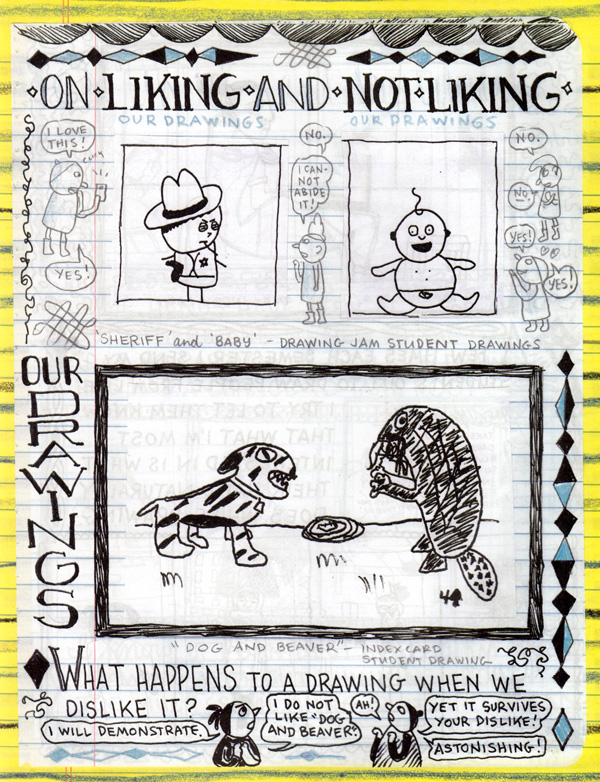

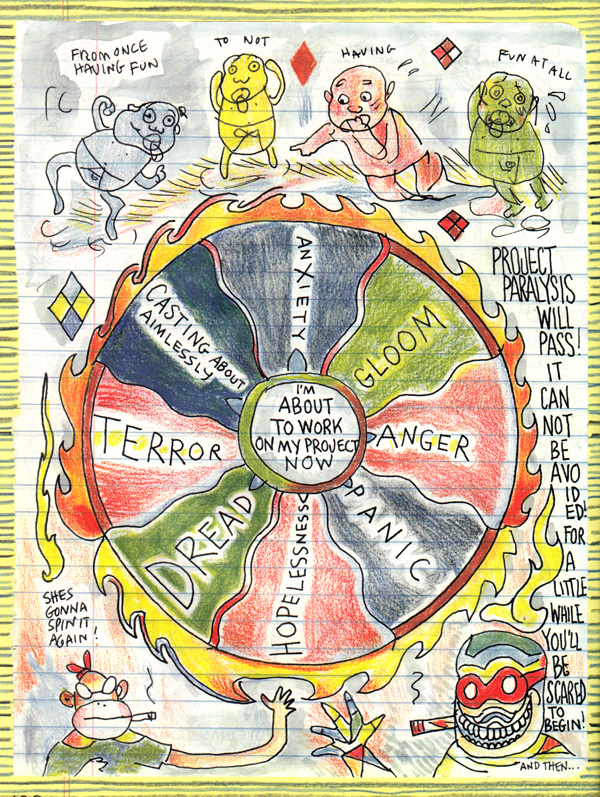

Hardly anyone has explored this delicate relationship between drawing and looking, drawing and experiencing, drawing and thinking with more rigor, wit, and insight than Lynda Barry, one of the greatest visual artists of our time. In 2011, Barry joined the faculty at the University of Wisconsin to teach a class titled "The Unthinkable Mind" – a wonderfully unusual interdisciplinary course exploring the biological function of the arts and the psychological mechanisms of the creative impulse by blending cognitive science, visual art, and writing. Barry's magnificently illustrated syllabus notes and class assignments, many of which she had released on her Tumblr throughout each semester, are now collected in Syllabus: Notes from an Accidental Professor (public library | IndieBound) – a slim but infinitely invigorating compendium of illustrated exercises, instructions, and meditations on everything from how to keep a diary (because, as we know, the creative benefits of doing so are vast) to memorizing things effectively to navigating the psychological phases of the creative process to why art exists in the first place.

Echoing Joan Didion's unforgettable reflections on keeping a notebook, Barry traces her own journey and what is to be gained by those endeavoring to master this simple, powerful practice:

I began keeping a notebook in a serious way when I met my teacher Marilyn Frasca in 1975 at the Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington.

I began keeping a notebook in a serious way when I met my teacher Marilyn Frasca in 1975 at the Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington.

She showed me ways of using these simple things – our hands, a pen, and some paper – as both a navigation and expedition device, one that could reliably carry me into my past, deeper into my present, or farther into a place I have come to call "the image world" – a place we all know, even if we don't notice this knowing until someone reminds us of its ever-present existence.

I wasn't quite 20 years old when I started my first notebook. I had no idea that nearly 40 years later, I would not only still be using it as the most reliable route to the thing I've come to call my work, but I'd also be showing others how to use it too, as a place to practice a physical activity – in this case writing and drawing by hand – with a certain state of mind.

This practice can result in ... a wonderful side effect: a visual or written image we can call "a work of art"; although a work of art is not what I'm after when I'm practicing this activity.

What am I after? I'm after what Marilyn Frasca called "being present and seeing what's there."

While Barry's exercises are decidedly and refreshingly practical, they don't shy away from the philosophical – she explores subjects like the eternal question of what makes good art and how drawing can change our already elastic perception of time. Along the way, she illuminates these questions by assigning readings as diverse as Emily Dickinson's poetry and Iain McGilchrist's The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World.

All in all, Barry's Syllabus makes not only tangible but also practically attainable the deep intuition that some of history's greatest minds have articulated – the idea that keeping a notebook or a diary, whether visual or otherwise, is one of the most consciousness-expanding ways of bearing witness to our experience and our journey through this world.

:: SEE MORE / SHARE ::

In 2014, I poured thousands of hours and heaps of love into Brain Pickings, but also incurred some hefty practical expenses along the way that can't be loved away. If you found any joy and stimulation here this year, please consider helping me keep it going with a small donation.

No comments:

Post a Comment